Level 1 entry foyer.

Looking south down the eastern atrium, with the main reception at its base.

Cafe spaces in the base of the western atrium.

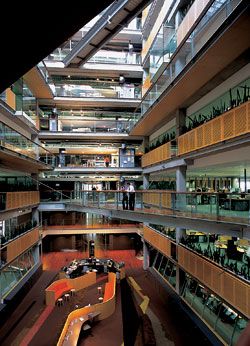

Looking down the west atrium. Both atria are crossed by walkways at various angles and penetrated by a stair, encouraging vertical and lateral movement through common areas.

Facade detail. The colourful facade is designed to reflect the diversity within.

Oblique view of the building edge, facing the space between the two buildings.

Overview from Victoria Harbour.

Behind every work of architecture lies the somewhat vexed question of property values, and the fact that good design always entails some element of risk. When bankers are involved, their skills at risk assessment may be so acutely applied that the role of the architect is reduced to mere parody. But if well deployed, the art of understanding value, as opposed to cost, can lead to innovation. As the first large-scale commercial venture at Docklands, the new NAB building constitutes a considerable risk. In light of recent troubles at NAB, a new office for 3,500 staff would not likely be undertaken today. But, initiated over four years ago by the previous CEO Frank Cicutto, it has been completed in time to assist restructuring. As current CEO John Stewart remarks, this building “landed in his lap”.

Designed by James Grose of Bligh Voller Nield, the building is located on one of the best sites in the Docklands. On the southern side of Victoria Harbour, adjacent to Harbour Esplanade, it is the first to enjoy a northerly aspect over the water. But the main advantage is the opportunity to move away from the typology of the office tower and adopt a more lateral profile. The building is in principle a tower lying on its side, with vertical hierarchy giving way to horizontal integration. This strategy is reminiscent of office parks such as those by Eero Saarinen in the late 1950s and early 60s or by Roche and Dinkeloo in the 1980s, designed as headquarters for America’s largest corporations. These buildings avoided the congestion of the city, enabling each inhabitant to enjoy a view of the surrounding landscape. But this isolation also cut off access to the services of the city.

At Docklands, NAB has avoided the typology of the tower while still enjoying an inner city location. The plan consists of four elongated floor plates running roughly north-south in a W formation. Between each pair of floor plates is a service core at the southern end and an atrium running down towards the water’s edge. The atria are crossed by walkways at various angles, their connection to the floor plates defined by “portals” or landings formed by support spaces with photocopiers and other facilities. Each atrium is penetrated by an open stair, encouraging vertical as well as lateral movement through the common spaces. At ground level, the eastern atrium contains an amphitheatre for large training sessions, while the western one contains a cafe with a variety of seats, plants and ornamental pools. Through the middle, dividing the building in two, is an external walkway, with a large door that can be lowered in windy conditions.

Across the entire northern or water’s edge, a long “verandah” space provides a series of common areas designed to take advantage of the water views. The verandah changes character as it fronts different parts of the building – with meeting or training rooms in front of each of the floor plates, “sunrooms” across each atrium and a “wintergarden” in front of the central walkway. The sunrooms and wintergarden are naturally ventilated, and a series of small balconies enable workers to venture outside when weather permits. Open kitchens at each end of the atria also emphasize the sense of hospitality, allowing workers to make their own lunch while they enjoy the sun, light and view.

Overall, the emphasis is on amenity rather than status, with the sleek surfaces of corporate culture giving way to a relaxed, casual feel intended to make work more enjoyable. Readers familiar with the principles of the “new office” developed by Frank Duffy will recognize the basic logic, namely that different types of work need different types of space, and that worker interaction in meetings or over lunch is as important, if not more so, than individual output from the confines of a workstation. Grose explored these ideas in the design of Campus MLC in Sydney, but this is arguably the first large-scale application to a new office design in Melbourne.

What is most surprising is how long it has taken for a reasonable alternative to the office tower to emerge. Service-intensive buildings designed to achieve floor plate efficiencies are not, in all honesty, the most enjoyable places to work – except perhaps for those with executive suites. Parodies such as Jacques Tati’s Playtime or Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant’s The Office provide little consolation for the sensory deprivation and isolation of the average workstation. Unfortunately, commercial attitudes to office space have been dominated by the so-called “Hawthorne Effect” – that managerial attention is more important to workers than the quality of the workplace. The research on which this is based, undertaken at the Hawthorne plant of Western Electric (a subsidiary of AT&T) in the 1920s, has been erroneously applied to office design ever since. Not only were the subjects of the original experiments undertaking repetitive manual tasks instead of clerical work (assembling telephone relay devices), they were also as adept as the researchers at manipulating the outcomes of the experiment.

Later efforts to improve the quality of the workplace, especially the bürolandschaft or “office-landscape” of the 1960s, were also of limited success. The promise of a more “natural environment” became for most people a loosely planned series of cubicles interspersed with pot plants, housed within an airconditioned office with deep floor plates and sealed windows. Reaction against these conditions led to much of the current European legislation mandating access to operable windows and views. Combined with the drive for sustainability, changes to office design are reconfiguring notions of value. In buildings such as Norman Foster’s Commerzbank in Frankfurt, Germany (1997) and Swiss Re headquarters in London (2004), atria designed for natural ventilation have led to greater interaction between staff, whose view of each other is not completely hindered by floor plates.

In contrast to the high-tech approach, Grose makes reference to that other great alternative to the office tower – the renovated warehouse. Industrial spaces converted for office use are often highly prized, not only for their high ceilings and natural light, but for their connection to the sheer physicality of industry through the weathered textures of brick and timber. In fact, the evolution of the office appears to have suffered from efforts to mark the distinction between white- and blue-collar work. At NAB, Grose has avoided “corporate” finishes in favour of more humble materials, especially timber, that would not normally be associated with a bank. The result is a light-industrial feel that pays homage to its maritime location, with floor plates labelled as “piers” and recycled wharf timbers used for signage. The tactility means that the walkways and staircases encourage interaction without inducing vertigo. On the verandah, the spaces take on a nautical edge, as the exposed services and concrete floors feel like an ocean liner sitting at dock.

By venturing outside of existing commercial parameters, NAB appears to have secured one of the best office spaces in all of Melbourne. But given security conditions, the real success of this building – its working interior – is something that only bank employees and their visitors will be able to experience. For the rest of us, the building will remain a fairly inscrutable, multicoloured box (a “Rubik’s cube on speed”, perhaps). The colours are supposed to refer to the diversity and vitality of the staff, and the way they engage with each other and with their environment. This is most successful on the northern, waterfront facade, where operable windows, sunshading devices and balconies give a hint of the richness and complexity within. Here, ground-level bars and cafes help enliven the waterfront promenade, the Docklands’ most important public space. On the remaining facades, a flatter profile is adopted, eschewing the play of surface that characterizes so much of Melbourne’s contemporary architecture. This is regrettable, especially given the prominence of the site on what will be the continuation of Bourke Street. Yet in this inversion of priorities, NAB may well, like the rest of Docklands, act as a counterpoint to our expectations of the city.

The architecture of the workplace

Overview of typical floor. The workstations are an innovative model, designed to NAB’s requirements using standard parts of a Steelcase range, with a few new pieces designed by BVN.

Detail of the west “cafe” atrium, showing the use of timber.

Graham Brawn locates National @ Docklands in the broader field of workplace change.

“The present is a time of great entrepreneurial ferment, where old and staid institutions suddenly have to become very limber” - Peter Drucker ›› ›› THE CHANGES IN workplace values and practices introduced by the Nationa Australia Bank team, and manifest in the design of National @ Docklands, are more than those enabled by the new and ever-changing IT technologies, and go well beyond the special qualities of the interior spatial planning and design. The translation of visions of better work practices and work environment values into an agreeably supportive and satisfying designed environment means that the project will stand out as an important office project of international significance. The built result is also a testimony to the benefits of a collaborative design process, one in which the means of achieving the desired ends need to be “invented” as part of the programming and designing process.

NAB recently acquired MLC - a financial services company based in Sydney - in part, to introduce the latter’s workplace culture into the bank. The acquisition reflected the bank’s realization that it needed to change its culture, as MLC had, from the work practices so important for growth of the industrial world and continued in the capitalist form of commerce to the knowledge-based practices needed for the contemporary information and service industry age. Acknowledging staff as a major resource in the organization, and the need to have a core set of visions and values with which they felt comfortable, was central to effecting a successful transition.

Rosemary Kirkby, formerly of MLC and now National @ Docklands joint project manager (with Peter Affleck), and James Grose, design principal of Bligh Voller Nield, have been key players, continuing the thinking they began at MLC. Together with their full team of consultants, suppliers and building owner representatives, they have developed a viable workplace ecology of architectural merit, achieved through new forms of practice, and within a very restrictive set of developer economic imperatives, all on an unforgiving site. Repeating the architectural and engineering forms of National @ Docklands without the conviction, theory and sensibilities of organizational behaviour and cultural change that underpin it is unlikely to provide the same synergies and benefits.

Contemporary change in the workplace has a long history, a knowledge of which helps us to appreciate the ambitions and achievements of this project. Its origins are in the work of Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915), the controversial systems engineer. Taylor is known for what became time and motion studies. He disaggregated work in steel mills into discrete components, each of which he timed. From this he developed more productive ways to do basic mill tasks, such as loading railway freight cars. For a long time Taylor was condemned as an efficiency expert who dehumanized the workplace. However, Peter Drucker has recently given a more complete appreciation of Taylor’s work and the importance he gave to his methods of “functional management” as being the vehicle for employee liberation, their increased monetary rewards and self-fulfilment:

“Taylor’s motivation was not efficiency. It was not the creation of profit for the owners. To his very death, he maintained that the major beneficiary of the fruits of productivity had to be the worker, not the owner. His main motivation was the creation of a society in which owners and workers, capitalists and proletarians, could share a common interest in productivity and could build a harmonious relationship on the application of knowledge to work.”

Drucker argues that this full dimension of Taylor’s message enabled the USA to so quickly gear up its industrial efforts during WW II and also guided the huge success of postwar industrial Japan.

The work of Douglas McGregor addressing the nature of employee-to-employe relationships has also had enormous impact on determining how employee satisfaction can positively affect corporate goals of increased productivity and profitability. This was firstly through his own teaching and work as a business executive and secondly through the work of many who came under his influence at the Sloan School of Management at MIT (1954-1964). One such colleague was Abraham Maslow, best known for his concept of the “Hierarchy of Human Needs”, through which he explained human motivation in terms of the importance of satisfying our survival and safety needs before our social and self-esteem needs can be addressed. McGregor’s students included Charles Handy and Warren Bennis. Handy is well known for foreshadowing changes in the nature of work and how organizations would need to change to attract and hold employees involved in the new forms of work. Bennis’s main contributions are in the importance of leadership over management - “Managers do things right. Leaders do the right thing.” Bennis also introduced “adhocracies” as the organizational structure that best fits projects required to bring about change through innovation and creative action.

McGregor, a social psychologist, is most famous for his “Theory X” and “Theory Y”. Theory X refers to the attitude that employees are generally lazy, dislike work, are not reliable and are incapable of accepting responsibility. It develops a “them and us” management mentality of control and overt supervision. In contrast, Theory Y sees that employees do want a sense of achievement and responsibility, are adult and can be trusted. It leads to a management model of support and encouragement. McGregor taught us that the need for continuing self-development fuels personal motivation. He also demonstrated the importance of social environments to satisfy the need for a sense of belonging, to gain peer recognition and affection, as well as the role of self-respect and achievement in feeling fulfilled.

Beyond these thinkers, we can also detect connections between the sensibilities of National @ Docklands and other management theorists, including Henry Mintzberg (strategic, and further work on adhocracy), Michael Porter (competitive strategy and competitive advantage), Rosabeth Moss Kanter (empowering individuals in the work force), Peter Senge (the learning organization) and Gary Hamel (strategic thinking as change agent and types of organizations as rule makers, rules takers and rule breakers). These influences, although not necessarily direct, have led the National@Docklands team to follow a form of ecological imperative. The occupied building is seen as a cultural artefact that reflects the values, attitudes and behaviours of an organization that supports the people and their activities, as well as the technologies they employ.

Closer to architecture, DEGW’s important work on the synergetic relationship between the processes of work and our built work environments has also had an impact. At National @ Docklands the number of workstation types has been kept to three. The conference room has been replaced with numerous places for groups to meet and work together, for short times and on special projects. These, and other places for private work, have access to free coffee, tea and fruit, and many are naturally ventilated. There is a commitment to environmental responsibility with easy-to-use recycling, rigorous processes to minimize hard copy filing, and access to fresh air and the outdoors. The workstations have been tailored to NAB needs using standard parts of a Steelcase range, with a few new pieces designed by BVN. The result is an innovative new model, achieved within the constraints of a formal bidding process. Timber finishes have been widely used to further the desired haptic qualities of the various spaces.

The work of Bennis, Mintzberg and Kanter helps explain the success of the method used by the NAB Docklands team in developing the project from the ideas to the reality we can now experience. For Bennis, leadership is about creating a compelling vision, translating it into action and then sustaining it. Such leadership, he tells us, is provided by “ideas people”, conceptualists and communicators of vision. It is clear that the NAB project leaders expected these qualities of all the key members of the team.

Mintzberg argues that adhocracies, as defined by Bennis, fit well with organization that need to constantly innovate and respond quickly to change in their markets. He describes two forms - operating and administrative. The former applies to creative units working in competitive environments, and the latter to research-based groups. The financial services industry reflects both forms. In an adhocracy, teams of equals work outside their “cells” and cut across boundaries of responsibilities, knowledge and experiences to solve the same problems collectively. This is a performance-based approach. The team agrees on what has to be achieved, and by when, and then works together to find out how to do it, determining along the way the balance between values, processes, policies, budgets, resources and built environment. Understanding how adhocracies operate makes design a more manageable process, while retaining the important advances made by Donald Schön in his 1983 book The Reflective Practitioner ›› Kanter, in addition to focusing on the importance of the right type of leadership, advocates participatory forms of planning and design, involving all user groups and all those who want to participate. She warns that without such involvement, deep, profound cultural change is unlikely. Indeed, there is a strong chance of disruption when effecting the changes, leading to less being achieved.

A wit once said, “Good architecture requires two ideas, that of the client and that of the designer. If the client doesn’t have one then the architect has to have two.” Rosemary Kirkby had a very clear idea about the future of work and the preferred workplace, and James Grose brought his ideas about a supporting architecture developed from years of practice before and since joining BVN. Their ideas have a symbiotic relationship and their sensibilities are reinforced by much current management theory. Under their leadership National @ Docklands had a very participatory planning and design process, involving wide collaboration from within the bank and with suppliers, including the developers. So they are justifiably confident that they have laid out a model and a product for use across more of the National Australia Bank. But other organizations and their design teams need to be aware that many of the innovations are not necessarily transferable without similar commitments to making change and similar sets of values to those that drove this project.

Images: Anthony Browell, John Gollings

BIBLIOGRAPHY

W. Bennis and R. Townsend, Reinventing Leadership: Strategies to Empower the Organisation (London: Piatkis, 1995).

Peter F. Drucker, Post-capitalist Society (New York: Harper Business, 1993).

Frank Duffy, The New Office (London: Conran Octopus Limited, 1997).

Rosabeth Moss Kanter, The Change Masters, Corporate Entrepreneurs at Work (London: International Thompson Business Press, 1983).

Carol Kennedy, Guide to the Management Gurus (London: Random House, 1998).

Abraham H. Maslow, Motivation and Personality (New York: Harper and Row, 1970).

Donald Schön, The Reflective Practitioner (New York: Basic Books, 1983).

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jan 2005

Words:

Scott Drake,

Graham Brawn

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2005