The objects on display at the museum float at eye level within cleverly hidden glass display cases. Image: Philippe Ruault

External views of the museum set among the wild gardens designed by Gilles Clément. Images: Philippe Ruault

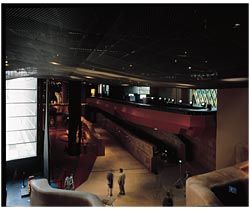

Overview of the main display area, with its two leather curving walls. The processes of transforming the artworks into part of the built fabric of the Rue de l’Universite building. Image: Philippe Ruault

Discussions with Lena Nyadbi about Jimbala and Gemerre (spearheads and scars) included a full-scale mock-up, which was rejected as the image lacked contrast. Image: Philippe Ruault

Jimbala and Gemerre carved into the plaster of the Rue de l’Universite facade. Image: Philippe Ruault

The final printed glass panels for Cloud being set into stainless steel panels in Leichhardt. The fresco of ten photographs by Michael Riley is installed on the ramp leading to the bookshop. Image: Philippe Ruault

Preliminary samples and methodology for Untitled (Wirrulnga), by Ningura Napurrula, developed at Eumundi. Image: Philippe Ruault

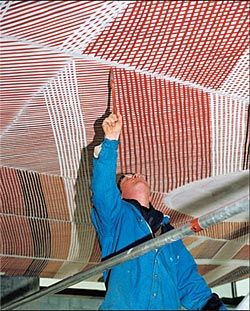

John Mawurndjul’s Mardayin at Milmilngkan being painted onto the bookshop ceiling. Image: Philippe Ruault

Installing Tommy Watson’s Wipu Rockhole on the third floor ceiling. Image: Philippe Ruault

Gulumbu Yunupingu describes the sequence of mark-making to be used. Image: Philippe Ruault

Museum Piece, 2006, by Judy Watson, on the glass facade of the bookshop. Image: Philippe Ruault

Discussion and preliminary sketch for an early version of Paddy Bedford’s facade piece based on Thoowoonggoonarrin. Image: Philippe Ruault

Interior of the bookshop, with Mardayin at Milmilngkan, 2006, by John Mawurndjul on the ceiling. Image: Philippe Ruault

The Universe, 2006, by Gulumbu Yunupingu, as seen on the second floor corridor ceiling. Image: Philippe Ruault

The vibrant colours and patterns on the ceilings of each floor are visible from the exterior facade. Image: Philippe Ruault

Museums carry a heavy symbolic load. They are weighed down by their collections, assembled by generations past, and often burdened by significant but dated buildings. Yet museums are expected to reflect current social and political trends as well as offer a range of opportunities from socializing over coffee and shopping to academic research. Less than a century ago European museums proudly displayed the cultural objects from Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas as evidence of powerful colonial empires. Now, new global relationships require different thinking and displays.

The Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, which opened on 20 June 2006 and cost 232 million euro, is intended by the French Government and President Jacques Chirac to be an enduring symbol of France’s new relationship with the non-European indigenous world. At the museum’s opening Chirac proclaimed, “We are putting an end here to a long history of disregard, and giving just consideration to art forms and civilizations too long ignored or misunderstood.” ›› About 280,000 pieces form the collection of the Musée du Quai Branly, of which approximately 3,500 are on permanent display. In the main, these are cultural objects from the indigenous peoples of Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas dating from the nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries.

However, there is also a unique collection of Australian Aboriginal art, which includes contemporary works. Apart from photography, this Aboriginal material is the museum’s only significant collection of contemporary art.

The vision proclaimed by Chirac at the opening is expressed in the dramatic architecture of Jean Nouvel. Nouvel won the commission for the new museum, placed prominently on the banks of the Seine and close to the Eiffel Tower, through an international competition. His Letter of Intent for the competition was titled “Presence-absence or selective dematerialisation”. In it, Nouvel advocated making the building disappear “out of our sight and mind, let [structures, such as fire escapes, railings and false ceilings …] step aside from the sacred artefacts on view and allow us room for communion”. He envisaged the museum as “a simple sanctuary without walls in a wood”, as “a place marked by the symbols of forest and river, and the obsessions of death and oblivion”.

Around and under the Musée du Quai Branly are extensive garden areas designed by Gilles Clément – two hectares of “wilderness”, albeit a manufactured “wild” place of unruly trees and bushes, trickling streams and meandering paths. Visitors “become explorers” and journey, through the gardens, to a central entrance beneath the museum, where they make their way along a 180-metre ramp to the display area. The main gallery appears to float ten metres above the gardens on twenty-six randomly placed metal posts. The Branly building, limited to a height of twenty-one metres, is partly hidden by a forest of trees, which at maturity are expected to reach the museum’s roofline. In a tour de force of nature, a vertical wall of growing plants, designed by Patrick Blanc and formed from 15,000 plants, covers an 800-square-metre curved wall of the administrative section of the museum, punctuated by square windows. “There is,” claimed Nouvel, “a mystery here.” ›› The focus on nature in many aspects of the museum’s architecture recalls, perhaps unintentionally, outmoded European associations of indigenous peoples with the exotic unknown and natural world. The ghost of “the noble savage” portrayed by French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau seems to haunt aspects of the architectural symbolism.

The interior of the museum echoes these allusions to the natural. The pathway through the collection is described as a river. The ramp leading up to the collection undulates in uneven humps and waves around a large glass storage core for musical instruments. The sounds of drums and other instruments are heard as visitors move through a tunnel until they finally emerge into the dark heart of the main display. Lighting levels are low to protect the light-sensitive objects. Daylight is filtered through a photomontage of jungle leaves over the massive front windows (200 metres long and nine metres high). Running parallel to each other lengthwise through the centre of the display area are two curving walls of about 100 metres in length and from 1.5 to 2.5 metres in height. These walls incorporate seats and spaces for multimedia screens.

They also establish a directional flow around the space as well as separate sections of the displays.

In the dim light, the walls appear to be eroded sandstone cliffs and the seats become little caves of shelter. On closer inspection these furniture walls are completely covered in a patchwork of light brown leather. Wonderfully extravagant, they indicate the quality of fittings throughout the building.

Stéphane Martin, Director of the Musée du Quai Branly, describes making a museum as “making theatre, not writing theory”. This was the guiding principle for the interior design. The objects are displayed “naked … just the objects”. Each piece is dramatically spotlit and most are displayed in glass vitrines in the round, while some larger wooden items such as slit gongs from Vanuatu and other stone pieces are in freestanding groups. The overall effect is stunning and sets a standard for display design that few museums worldwide could even imagine.

In general, the works on display are arranged according to aesthetic rather than cultural considerations. However, this emphasis on the objects as art can be a pretext for avoiding contextual consideration. It could be argued that in postcolonial times, art is a much safer category in which to place collections, allowing aesthetic considerations to overshadow darker social and political histories and any ownership difficulties. Throughout its planning and development, the Musée du Quai Branly was the subject of intense arguments and even demonstrations and strikes by some anthropological staff. They were not convinced that the cultural objects of other societies, often produced for very different purposes, should be treated simply as “art”.

Branly attempts to respond to these issues through extensive multimedia installations as well as a teaching and research focus. Events, theatre, dance and musical performances will be an integral part of the museum’s programme, using the numerous auditoriums and performance spaces incorporated into the museum, including an outside amphitheatre. One of the building’s four wings houses educational facilities, including a library with over 180,000 volumes and a multimedia centre.

The Interdisciplinary Research Centre occupies another wing and houses specialist research facilities, including collection study areas and conservation laboratories.

This research centre for the museum, sited on Rue de l’Université, emerges from the existing streetscape of neo-baroque nineteenth-century buildings. Its walls, floors and ceilings feature work by eight Australian Aboriginal artists. On the outside wall is an architectural rendering of a painting by Lena Nyadbi, a Gija artist from the Kimberley region in north-western Australia. On each level of this building are various Aboriginal ceiling murals.

These include a depiction of Garak – The Universe by Arnhem Land artist Gulumbu Yunupingu, a painting by Pintupi artist Ningura Napurrula depicting her central desert homelands, Pitjantjatjara artist Tommy Watson’s central desert design in enamelled metal, and a painting by senior Kuninjku Arnhem Land artist John Mawurndjul. Near the ground-floor museum staff entrance is a painting designed by Paddy Bedford, and outside along Rue de l’Université, the window glass has been etched in designs by Judy Watson, through which can be seen a photo series by Michael Riley.

The incorporation of Aboriginal art was the idea of Jean Nouvel, with the cost of the commission met jointly by the museum and the Australian Government. Aboriginal art curators Brenda L. Croft and Hetti Perkins advised on the selection of works.

Australian architects Cracknell and Lonergan, a practice with considerable experience working with Aboriginal communities, implemented the project.

This included technical adaptations of the art, and they were in the midst of negotiations between artists and curators in Australia and the museum and Nouvel’s team in Paris. Cracknell and Lonergan Architects used a warehouse in Sydney as a workshop for testing how to translate the painted designs into architectural forms. For example, laser-cutting templates for enlarging the brushstrokes of Lena Nyadbi’s painting into a rendering technique suitable for transforming the outside wall of the research wing into a textured surface were conducted at this base. And exercises in the textures of paint. After various experiments the architects would then show examples and discuss aspects of the scale of the designs to the artists, often in their remote communities. Each of the artistic projects required different yet demanding techniques to achieve the appropriate result.

Mawurndjul’s bookshop ceiling and Watson’s and Riley’s works in the window are the most visible to the general public. There is limited access to the other Aboriginal works. However, clever mirroring makes snippets of the ceiling paintings visible in the street below, and lighting at night makes the ceilings even more visible.

The French have made a bold political gesture with this new museum. It is easy to find questions that are not well answered, such as the absence of contemporary art in the museum from the indigenous peoples of France’s former colonial regions. Or to scoff at some of the overblown rhetoric associated with the museum. Yet to dwell on these aspects is to ignore the phenomenal achievement of building such an impressive display space for the artistic accomplishments of non-European cultures. No such museum exists elsewhere in the world and Ateliers Jean Nouvel’s rambling, unconventional building is a similarly bold statement.

Peter Naumann is researching Aboriginal art in European museums through the Centre for Cross Cultural Research at Australian National University.

MUSÉE DU QUAI BRANLEY, PARIS

Architect Ateliers Jean Nouvel.

AUSTRALIAN INDIGENOUS ART COMMISSION

Architect Cracknell and Lonergan Architects— project team Peter Lonergan, Julie Cracknell, Matt Fearns, Chris McBride, Aryan Mansor, Romy Farmer, Jan Cracknell.

Curators Brenda L. Croft, Hetti Perkins.

Artists Paddy Bedford, Michael Riley, John Mawurndjul, Judy Watson, Tommy Watson, Ningura Napurrula, Gulumbu Yunupingu, Lena Nyadbi.

Artisans Brett Gibson, Rosie Gordon, Michael Place, Jeremy Cohen, Jenny Hayman, Peter Harris, Martin Say, William Undery, George Hammond, Peter Flemming, Peter Lucas, Richard Lucas, Nelson Lucas, John Shipton, John Creighton, Lance Nichols, Frank Villy, Samantha Hawken.

Other collaborators Australia Council for the Arts; Embassy of Australia, France; Embassy of France, Australia.