“The great hawk of the beach is outstretched, point to point, quivering and hunting.” – Les Murray, “On Home Beaches”1

The “great hawk” of Les Murray’s poem burns into focus as you slide into the great arc of Bondi from the north. The beach brims with an almost surreal natural beauty, oblivious to the burden of the cultural mythologies vested in its image. Its urban counterpoint, the wall of buildings that cups the amphitheatre, is more knowing – a jumble of faded pastel grandeur and gleaming ambition, each one jostling to defend an unimpeded seaward gaze. At the heart of a place that could not be more intensively “watched” is the new home of the beach’s renowned “watchers,” the North Bondi Surf Life Saving Club.

The club’s moribund red brick and concrete tile ancestor was bereft of architectural ambition and public spirit. The damage inflicted by relentless onshore weather conditions saw the club facing a program of extensive and costly repairs. Club member and architect Peter Colquhoun saw a moment to be seized – a chance to invert the bleak sensibility of the introverted bunker and more aptly reflect the spirit of generosity that underpins this community of volunteers. Durbach Block Jaggers was enlisted to the cause and, once the overwhelming advantages that an entirely new building could offer became clear, chairperson of the club Ben Griffiths and a cohort of the membership began the arduous task of raising the funds that would eventually enable the building’s construction.

This nimble little building – largely inaccessible, yet widely public-spirited – is quite a paradox. Its lean budget has been packed into its twinkling armature and while most may not enter, their eyes may roam with impunity. From every side the volume is punctured and porous, drawing the public gaze through the building to the landscape and from the beach back to the urban scene.

The softened ‘eroded’ form settles into the site, rather then dominating it.

Image: Anthony Browell

From the street, a horizontal tableau of receding headlands is punctuated by the rise and fall of gymnasium weights, while on other faces small pieces of the building peel outwards, seeking acknowledgement from fast and slow movers alike. The building orchestrates its public engagement in a highly discriminating fashion, balancing its desire to make contact with a need to provide the requisite privacy within. To most, it is an exhilarating flirtation, yet to be consummated.

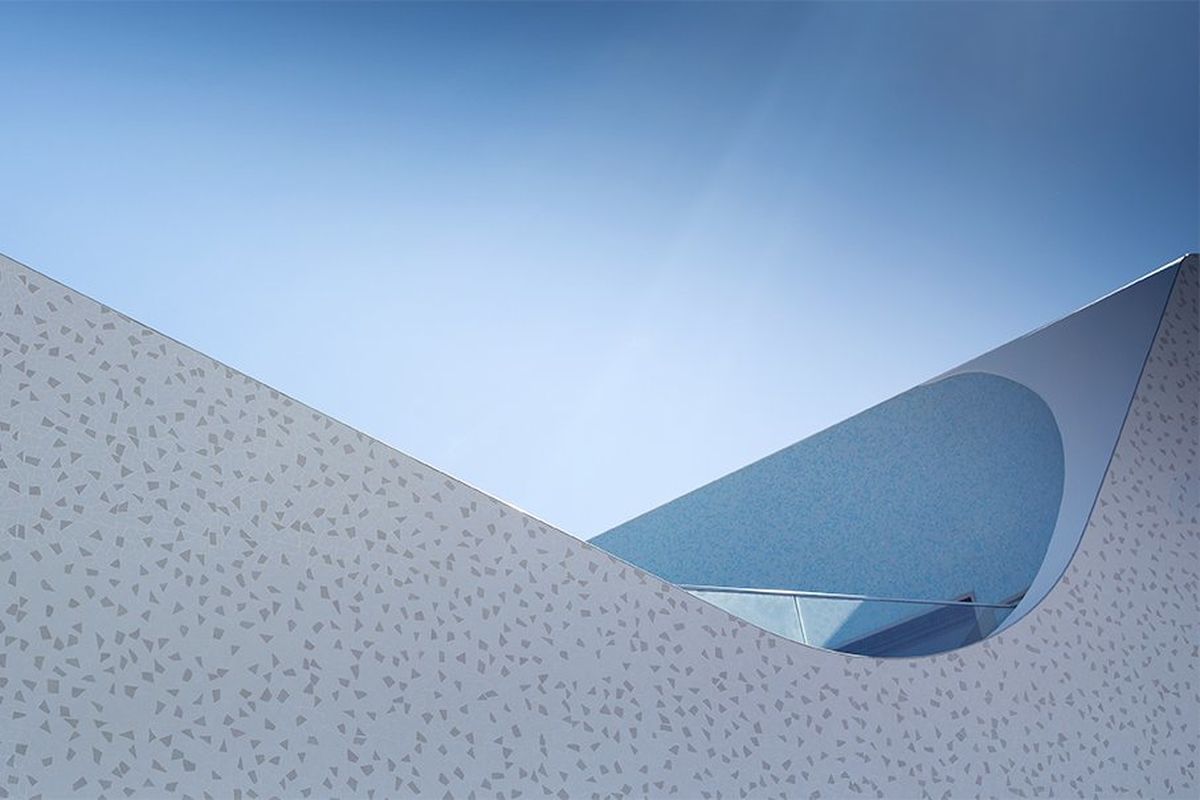

The swooping upstairs parapet: a nod to the coronet peaks of Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp chapel.

Image: Anthony Browell

On the beachfront, a wide concrete bench offers a place to rest beneath the curling parapet shadow as it makes its daily pass of the promenade. A large basement holds all of the “floating” tools of the trade, while the first aid room, nippers and juniors clubs and changing rooms open directly off the beachfront. A tapering concrete stair offers access to a long, thin balcony on the first floor. This is a truly powerful space fashioned only from concrete and shadow – an inky incision in the surrounding form, where the signature red and yellow quadrant caps align and adopt their habitual sweep of the horizon. The thinness of this band, the emphatic weight and raw muscle of its soffit and its deep shadow decouple it from place, amplifying the distance between observer and observed. Above, a looping intaglio of the clouds and sun intimates the building’s otherworldliness. Much has been written of Durbach Block Jaggers’ affinity with Le Corbusier, but here the master’s force is palpable.

Ocean views are framed in perfect proportions.

Image: Mark Syke

The highly concentrated nature of the building’s sculpted form and its location on the beachfront evoke associations with the observations recorded by Claude Parent and Paul Virilio in Bunker Archéologie, their 1958 survey of military bunkers of the Atlantic coast. They noted: “The geometry is no longer so assertive. It is eroded, worn. The angle is no longer right but rounded, to prevent scaling by enemies; the masse is no longer based on the ground, but centred within, independent, capable of movement and articulation.”2 At Bondi, it is not scaling by the body but by the eye that is resisted. Each time the eye reaches for an edge on which to measure the building, its curving form rolls away. The volume’s independence is also crucial. Upon entry, the relationship with the site is ruptured; a deliberate dislocation that enables a more purposeful reacquaintance to be made on the journey through the building.

The upper-floor outdoor observation deck between meeting room and members’ lounge.

Image: John Gollings

The formal entry is accessed from both street and promenade. As visitors enter the body of the building, a decisive physiological transformation begins. The noise of the surf is hushed, the light level diminishes and the space squeezes into a double-height hall that links street to promenade. From the higher street level, the viewer is offered a cinemascope window of sea – a looping silent film of the lifesaver’s patrol. On the walls in this Hall of Champions, members past and present surveil the space from within framed portraits. The gymnasium occupies one side of the plan, while a divisible training room holds the other. A caretaker’s flat is tucked into a crook against the street.

A taut, looping stair leads up to the top of the building, teasing with a tangential street view at the landing in order to delay, until the very last moment, the visual reconnection with the horizon. The upper floor holds events spaces, a commercial kitchen and an outdoor terrace, but the functions are utterly incidental. This level of the building operates as an exquisite littoral observatory. Turning left towards the sea for the final time, the building isolates, frames and presents a constellation of elements for intimate scrutiny: a miniature porthole of sky, the flats and rocks of Ben Buckler, windsurfers lining up off the point. Each time you move, these lenses reframe, reorient and refocus, alternately taking in the southern headland, the Icebergs, the children’s pool, silver coloured sand. Virilio’s observations come to mind again: “We broke, for a while, the atrophied envelope of the sentiment of reality, to replace it with the sensation of this reality.”3

The long, narrow first floor balcony is an “inky incision” of concrete and shadow.

Image: Anthony Browell

The detailing of each “lens” sharpens the distinction between the suspended artefacts. Some windows defy distance with frameless glazing and black reveals, while others are inset and thickened, isolating and dislocating elements. Others, still, are trimmed with mirrors that draw fragments into eccentric, kaleidoscopic adjacencies. At the centre of the plan, the geometry of the bay inflects the volume, scooping out a terrace where the elements are reassembled into their natural order beneath the resolute datum of the horizon.

Returning through the strata of the building, one is guided by a series of arced erasures seemingly worn into the ceiling plane, and tumbled back into the magnesium light of the esplanade. The building is equivocal, its rounded carapace seemingly in the process of acclimatizing to place rather than emphatically occupying it. This lack of surety hints at the necessary detachment of the observer.

Too often, the natural beauty of Sydney is so overwhelming that we inoculate ourselves against a more complex understanding by total submersion in its ubiquity. Here is a beguiling vessel, in which we are asked to break our easy truce with the familiar. “Everything that one thinks one understands has to be understood over and over again, in its different aspects, each time with the same new shock of discovery.”4

1. Les Murray, “On Home Beaches,” Collected Poems (Australia: Penguin, 2002).

2. Paul Virilio and Claude Parent, Nevers: Architecture Principe (Orléans: Editions HYX, 2010).

3. Virilio and Parent, Nevers.

4. Marion Milner, An Experiment in Leisure (London: Routledge, 2011).

Credits

- Project

- North Bondi Surf Life Saving Club

- Architect

- Durbach Block Jaggers Architects

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- DBJ project team: Neil Durbach, Camilla Block, David Jaggers, Stefan Heim (project architect), Erin Field, Deborah Hodge, Mitchell Thompson, Lisa Le Van;, North Bondi SLSC project team: Peter Colquhoun, Grant McMah, Peter Strachan, Ben Griffiths, Mark Cotter, Peter Zieme

- Architect in association

-

Peter Colquhoun

- Consultants

-

Accessibility consultant

Mark Relf

Certifier Tom Miskovich and Associates

Facade engineer Surface Design

Heritage Urbis

Hydraulic engineer Whipps Wood Consulting

Lighting Zumtobel

Mechanical, electrical and fire engineer Cardno ITC

Planner Mersonn Pty Ltd

Project manager Carter Building and Design

Structural engineer M+G Consulting

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

Type Sport

Source

Project

Published online: 14 Feb 2014

Words:

Laura Harding

Images:

Anthony Browell,

Jeannette Lloyd Jones,

John Gollings,

Mark Syke,

Natalie Walsh,

Stefan Heim,

Tim Granter

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2014