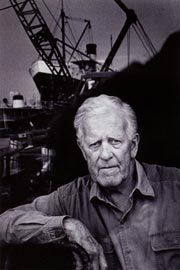

David Moore, portrait by Anthony Browell.

David Moore, portrait by Anthony Browell.

David Moore, portrait by Anthony Browell.

When David Moore died at the end of January this year, his family lost a muchloved father, we lost a good friend, and many photographers lost an encouraging mentor.

Australia also lost not just a great Australian, but one of our best and most important photographers. David was a father to Australian photography, in the same way that Robert Klippel was father to sculpture, Fred Williams to painting, and Gordon Andrews to design.

David called it quits on 23 January 2003, a couple of days before his retrospective show was to open at the National Gallery: he had become so weakened by cancer, that he couldn’t get to Tasmania for his customary summer holiday there. He had, however, chosen one of his favourite places – Balls Head Reserve on a Sydney Harbour headland near his home – for his memorial service, where his family and friends gathered to say goodbye.

For more than fifty years, David produced standout work, for clients

and for himself. But, most importantly, this body of work advanced the recognition and awareness of photography in this country. Through the Australian Centre for Photography, which he founded with Wes Stacey and others in 1974, his many exhibitions and nine books, he promoted the appreciation and importance of photography. He prepared the ground, laid the paths, for photographers who would follow him. There are many who value their moments with him, and whose careers and life paths have been enhanced by his own experience, advice and generosity.

Always one to have a project under way, David was an ordered man, a pragmatic fellow who laid out plans, assembled the necessary elements, and went about achieving his visions.

Planning, production, preservation, promotion, he made sure he got it all right. He was admired by his peers for his ability to consistently do great work, to promote that work elegantly, and to stay a contemporary artist and photographer; to always be a man of his time.

Growing up with an architect father and brother, and working as assistant to Max Dupain, David developed a respect for architecture, particularly architecture in a built-form-in-thelandscape sense.

Following his return to Sydney in 1958, after seven years establishing an international reputation with the photojournalist magazines in Europe and America, David set about illustrating to Australians the value of the their own visual arts, and one of his, and Craig McGregor’s, first projects became the classic 1969 publication, In The Making.

During the 1960s, 70s, and the early 80s, he photographed with many architects, including John Andrews, Col Madigan, Ian MacKay and especially Philip Cox, with whom he expressed his passion for the Australian vernacular in the 1999 book Functional Tradition.

Never one to be distracted by fashions or trends, he was uncomfortable with large format photography, preferring to shoot more freely and exploratively with medium format or 35 mm.

One of David’s last projects, a photographic essay covering the construction of the Glebe Island (Anzac) Bridge, brought together all his skills – as an artist, a photojournalist, a portraitist, an architectural illustrator – in all, as a marvellous visual storyteller.

Much has been written about David’s life in photography since his death, but there was another life, and another man altogether at home in the workshop, in the shed, and in the bush, down in Tasmania. David and his partner Toni McDowell restored a small but proud collection of timber buildings in their other home there. David reckoned he could make anything, and indeed did, including a wetland area, complete with a water-pumping windmill.

He made stone walls, a canoe, a Jimmy Possum chair. He repaired or restored anything he felt was of importance, and was never happier than when pottering around, making things work, or finding something wonderful somewhere unexpected.

Despite all his achievements, David would think that his life had been cut short, that there would always be pictures to take, things to make, and days to enjoy.

His legacy is in the vast body of work he left us, and maybe in one of his favourite sayings, “Wouldn’t be dead for quids!”.

He is survived by his partner of 24 years, Toni McDowell, four children with his former wife Jenny Blain, and six grandchildren.

Anthony Browell is a Sydney-based photographer. he would like to thank Toni McDowell, David Potts, John Gollings, Lisa Jasprizza and Philip Cox for their assistance in putting these thoughts together.