The Parkroyal on Pickering occupies a unique space in the Singapore CBD, mediating between the high-rise buildings of Raffles Place and the shophouse neighbourhood of Chinatown. Despite its being a “sure thing” as the only three-star hotel so close to the demand of the city’s commercial and tourist areas, no energy has been spared by owner, operator or architect in creating a building that is a destination in itself.

The block-sized project consists of a hotel of three linked towers in an E-shaped plan, on a podium shared with a somewhat downplayed office building (leased early in development to a government agency, so not “speculative”). The front of the building faces north-east over Hong Lim Park, an informal garden most notable as the only approved venue for non-licensed protests and at times teeming with activity like that anticipated on the terraces of the hotel. While the design of the park is undistinguished, its bounding street trees have magnificent canopies as high as the Parkroyal’s podium and easily coopted into the landscape of the pool terrace. At lower levels the interplay of trunks and branches extends the trabeated detailing of the interior.

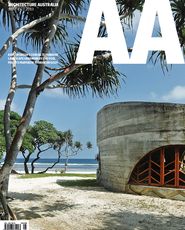

The heavy yet “eroded” base of the building represents WOHA’s interest in “topographical architecture.”

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Viewed across the park, the building is heroic and dynamic, most reminiscent of Antonio Sant’Elia’s illustrations for his futurist manifesto of a century ago. This design similarly strives to abandon “the monumental, the heavy, the static” with an enriched “sensibility with a taste for the light, the practical, the ephemeral and the swift.” Sant’Elia’s focus on circulation led to an architecture somewhat at odds with his written goals. WOHA’s overlay of natural systems softens the effect of revealed road and walkways and after decades of collective cogitation moves us closer to a viable vertical city.

The recessed ground-floor public areas are controlled right to the street edge.

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

WOHA has been exploring “topographical architecture” since its Circle Line subway stations of 2000. For those schemes, cleft but not subterranean, the focus was on the treatment of canyon walls. The later Iluma mall (now Bugis+) had an interior that was fit for spelunking. The Parkroyal represents another erosive type, the mesa. A decision was made early to save time and money by not excavating a basement. As available floor area would be expended well before the height limit was reached, it was possible to elevate the car park to levels three and four, creating a substantial geological podium. The ramp spirals around the office tower core, bypassing the recessed hotel lobby and meeting rooms and capping them with an arcing, greenery-fringed visor. Limited back-of-house functions (administration is accommodated off-site) are housed at the rear of levels one and four, the solid backdrop to ground-floor public areas being dematerialized by mirrors and green walls internally.

The open, planted and naturally ventilated bridging alludes to the typical form of neighbouring Housing Board flats.

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

A super-scale colonnade, reminiscent of Paul Rudolph’s condominium in Singapore of that name, supports the alternative reading of the soffit as a tree canopy with giant trunks. The ground plane is controlled right to the street edge with generous planting and covered walkways. The lobby and dining area are elevated slightly above passing pedestrians and traffic, the vertical transition handled by cascading water and planting on both sides of the insubstantial glass facade. At the narrow south-eastern end a bar terraces down to the footpath, welcoming wandering drinkers from Raffles Place.

A lantern pavilion, or “birdcage,” is cantilevered over the pool on level five.

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

The meeting suites on level two connect formally to the recreation deck above with the first appearance of “birdcage” or lantern pavilions, here used as booths in the business centre and to rail the upwards spiralling staircase. A rippling mirrored ceiling alludes and alerts to water overhead. The pool on level five cascades into a garden that loops the podium top, complete with a three-hundred-metre jogging track. Heavy timbers project over the water, upscaling similar treatment in the lobby, with light gangways spanning to suspended cabanas. Vines drape cylindrically through perforations in the soffit, another lantern intimation.

The double-loaded wings of guestrooms rise from level six. As shade is cast at an urban level, by SOM’s One George Street in the morning and by public housing blocks in the afternoon, sunscreens are unnecessary on the facade, which is plainly rendered in a dark reflective glass intended to fade into the sky. Elevational elaboration resisted, investment is instead made in sculpting garden terraces at four-floor intervals and in managing the mullions to integrate with internal planning and furnishings.

Additional rooms hang off a single-loaded access corridor. Its open, planted and naturally ventilated bridging both alludes to the typical form of neighbouring Housing Board flats and replaces the green view that they lost with the construction of the hotel. Two hundred percent of the land area of the development was replaced as garden and green wall, a significant achievement but only a stepping stone to the 700 percent WOHA is achieving at its Oasia Hotel, under construction a little further from the CBD.

Bathrooms steal glimpses across the room via wide sliding dividers.

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

The jointing of the ribs to the spine is nicely articulated, with spiral escape stairs or lifts occupying the internal corners. Only two rooms per floor look across the back of the building; the remainder enjoy views of the hotel’s own gardens or of the city to the north-west and south-east. Bathrooms also have an outlook, being positioned behind the facade or, for the lower grades, stealing glimpses across the room via wide sliding dividers.

The decoration develops elements of classical Chinese design: lightly layered screening of spaces, indirection of approach and circulation, and mortised and frame-and-panel wood detailing. The modulation of the facade is shadowed in carpet patterns and a trellis of light timber filling the window bay and supporting side tables, mirrors and lamps. Public and personal scales are linked by a Mondrianesque, incisive shifting of focus, then magnification.

A club lounge on level sixteen is open to any guest paying the entry tariff. The lounge is internally screened into living and dining areas, with a large communal table set with Straits Chinese tiles and an open, domestic-style kitchen. A library is well stocked with the collected works of WOHA, an initiative of the perhaps smitten general manager. The lounge opens onto a roof terrace suitable for evening functions and to be recommended as an alternative to the much-hyped surfboard spanning Marina Bay Sands.

The Parkroyal on Pickering achieves a fine balance of the geological and the cultural. A heavy yet eroded base is touched lightly by latticed volumes. WOHA’s “breathing architecture” manifesto is realized in a building that sustains its own ecosystem; dragonflies hover over the garden. The vertical city, at least in the tropics, can work.

Parkroyal on Pickering received the Hotel award at the 2013 INSIDE Awards.

Credits

- Project

- Parkroyal on Pickering

- Architect

- WOHA

Singapore

- Project Team

- Wong Mun Summ, Richard Hassell, Donovan Soon, Sim Choon Heok, Toh Hua Jack, Bernard Lee, Amber Dar Wagh, Mappaudang Ridwan Saleh, Evelyn Ng, John Paul Gonzalez, Josephine Isip, Goh Kai Shien, Luu Dieu Khanh, Tan Szue Hann, Alen Low, Pham Sing Yeong, Vanessa Ong, Novita Johana, Andre Kumar Alexander

- Consultants

-

Acoustic consultant

CCW Associates

Facade consultant Meinhardt Facade Technology

Greenmark consultant LJ Energy

Landscape consultant Tierra Design

Lighting consultant Lighting Planners Associates

Main contractor Tiong Seng Contractors

Mechanical and electrical engineers BECA Carter Hollings & Ferner

Quantity surveyor Rider Levett Bucknall Singapore

Signage consultant Design Objectives

Structural and civil engineer TEP Consultants

- Site Details

-

Location

Singapore,

Singapore

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Commercial, Hospitality, Interiors

Type Bars, Hotels / accommodation

Source

Project

Published online: 10 Dec 2013

Words:

Fiona Nixon

Images:

Patrick Bingham-Hall

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2013