Paul Pholeros is one of the founding directors of Healthabitat, an Australian company established to help improve the health of disadvantaged people, particularly children, by improving their living environment. For more than two decades, the company has worked in remote and impoverished communities around Australia and the region, tirelessly working to improve life within these communities, often in the absence of government funding or political willpower. Here, Pholeros talks with Mercedes Mambort, creative director of the upcoming 2015 Australasian Student Architecture Congress, where he will be presenting.

MM: Having spent a year travelling to remote aboriginal communities throughout the Northern Territory I have experienced firsthand the complexity and, paradoxically, the beautiful simplicity of life in the bush. There are many young people who are very keen to contribute to this area in meaningful ways. You have been successful in getting projects off the ground without the help of government bodies. What advice do you have for people who would like to make an impact in this realm? What are some practical ways to get projects and initiatives started?

PP: For 30 years, Healthabitat has had both help and hindrance from governments – state, territory and federal. Governments should help as they have responsibility for the well-being of all, not just some, of our citizens.

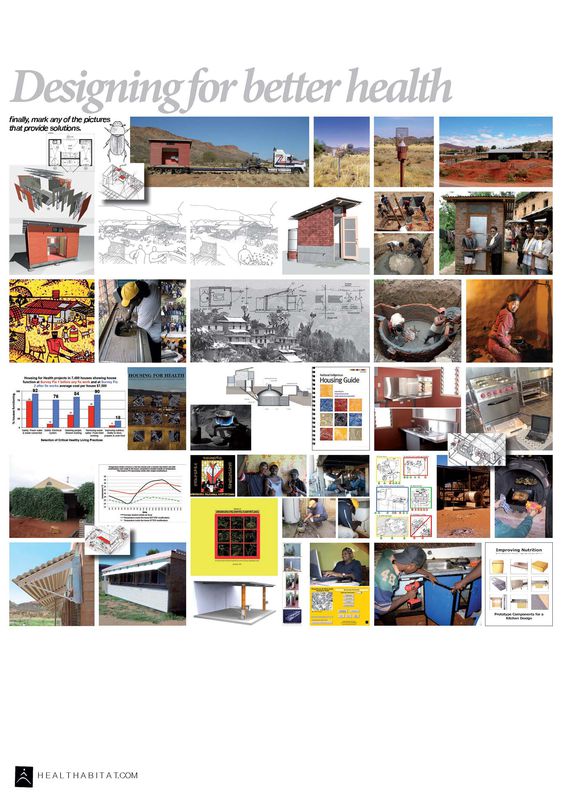

To get projects started… get an invitation from the people who need your services and make sure they agree what the problem is and why you are there. Make a change to the lives of some of the people you are working with on the first day of the project, no matter how small or apparently insignificant the change. Make sure you bring the whole community along with the content of the work, not just the leaders and not just those funding the project.

MM: What changes in attitude might first have to happen in government/society before community-centered Indigenous work becomes better able to facilitate the autonomy currently missing from some aspects of Indigenous community life. Is this the role of an architect in your opinion?

PP: It’s the role of all players, citizens and professions, to change the current appalling situation. Governments really can only allocate and spend money, they have little connection with the people they are meant to be representing and no link to the poorest and most isolated people. This lack of real connection has led to a language and a set of clichés, agreed by all, that pretend concern but are meaningless – “culturally appropriate,” “ the need for education,” “cultural sensitivity,” “closing the gap” etc.

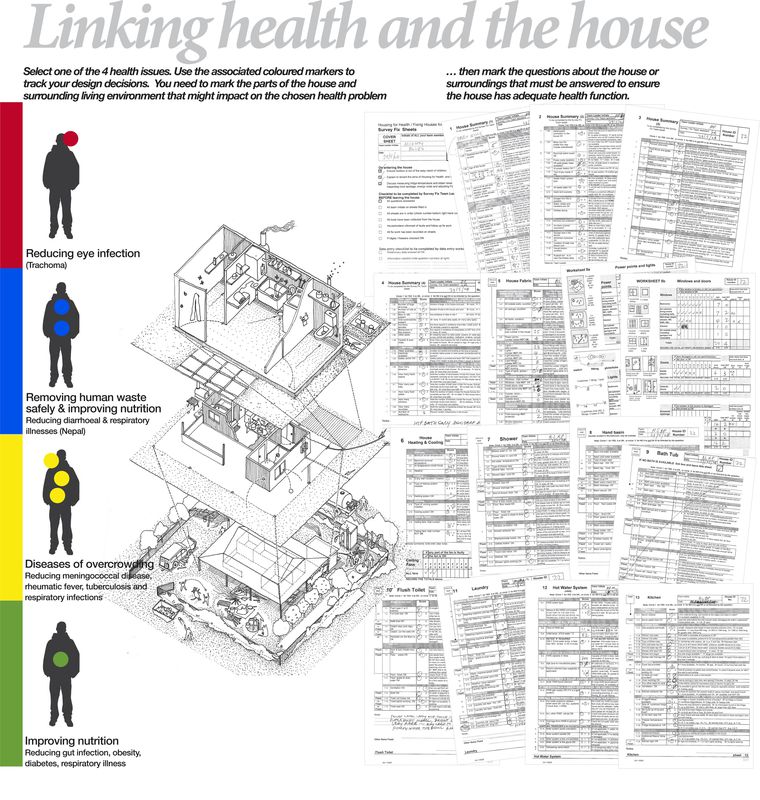

We need more action not more weasel words. Generally, architects have not been trained or educated to tackle many of the actions needed nor will our work lead projects with complex goals. Not all problems have a building solution. By using our design skills, combining with other professions and re-focussing our work on the well-being of people, not just making objects, we may have an important contributing role. I see this as a non-heroic role involving a lot of dirty work and hard slog.

MM: You would have lived/spent time in remote Aboriginal communities. Which ones? What was the biggest impression left on you from these communities?

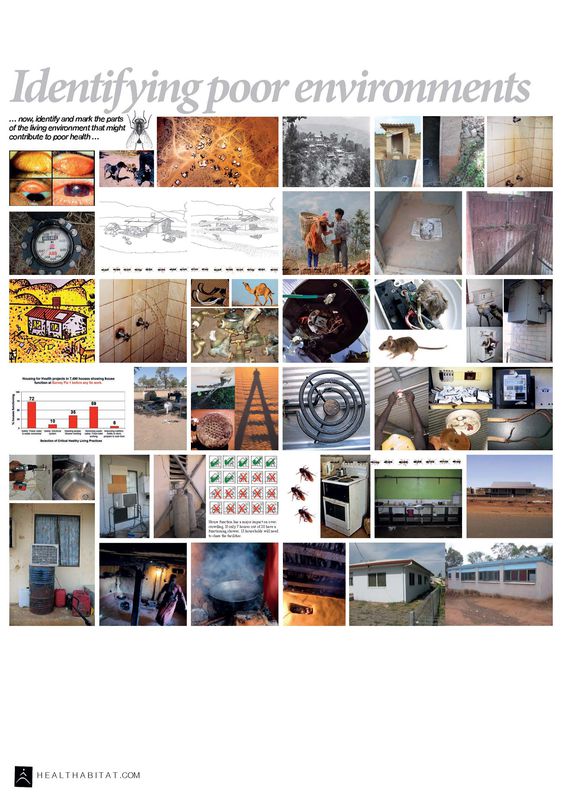

PP: There have been too many visited to name, and Healthabitat has had over 200 projects around Australia. The communities visited are often in spectacular places and the people we work with have thousands of years of knowledge about the place. The majority of our Housing for Health teams are made up of local Indigenous people and I have always been impressed by their hard work, humour and generosity. They understand the goal of the work is to improve the health of their children and work hard to help achieve this goal. Their generosity and enthusiasm is remarkable given the “developing world” living conditions they battle with every day. People live in grinding poverty, unimaginable to most Australians. More frustrating is the fact that they are regularly promised large sums of money that never reach the real target or improve the living conditions and health of the people who need it most.

MM: Do you think implementing Indigenous cultural studies into architecture courses in Australian universities would better equip architects with both the confidence and knowledge to work in this realm?

PP: Indigenous “action” rather than “studies” may be a better way to frame a course. I would lose the “Indigenous” tag and shape the course for all people, of any culture – Nepali culture, Bangladeshi culture, South African culture, New York City culture and so on. Healthabitat works in many cultures and we need to think of the common elements, not just differences, and why we have been invited to work with any particular group. The culture of poverty is the common thread between all our projects.

Local cultures can take care of their own business without us needing to learn all about them… if we really work with local people then they will direct how and where we work and their culture is protected.

MM: Thank you so much for your time. I am very much looking forward to hearing more from you at the 2015 Australasian Student Congress.

Paul Pholeros is a speaker at the 2015 Australasian Student Congress: People, 2–4 July in Melbourne. Tickets and information here.