The audio quality is poor; mostly hiss and crackle, with voices so submerged and distorted they are just a continuous murmur. As the remaining record of a 1979 interview with Peter Johnson (Dean of the Faculty of Architecture at The University of Sydney from 1968 to 1986), this second-generation audio cassette is of no use.

In 1972, during Johnson’s tenure, architecture students at the University of Sydney went on “strike,” but piecing together the details of that moment is proving difficult. Architectural historian Jennifer Taylor, in her second year teaching in the faculty, saw student unrest and upheaval in the air: “the students had long hair, were against capitalism and against architects who designed buildings.”1 The strike forced the cancellation of classes and it is said the building was scrawled with the words “pig architecture.” A connection was being drawn between the local educational context and the discontent, protest and social revolution that spread around the world in the late 1960s.

Four years earlier, in May 1968, French university students had marched on the streets of Paris, sparking an international wave of student activism. By the beginning of the 1970s architecture students had staged protests, occupations and strikes in architecture schools in Italy, France, England, Germany and Belgium, as well as in iconic US architectural schools, including Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Columbia University, the University of California, Berkeley and Harvard University.2

The University of Sydney provided a formative context for the local architecture strike, having experienced a build-up of student activism in the 1960s (for example, the 1965 Freedom Ride through rural Australia, led by Charles Perkins). The character of the student body was changing, reflecting wider changes in Australian society. By the middle of the 1960s, 40 percent of Australians were under the age of twenty, and baby boomers were swelling the university’s student numbers.3 Australians were beginning to enjoy the privileges of relative prosperity. Even during the 1960s, before the abolition of university fees by the Whitlam government in 1974, most students were being supported by Commonwealth scholarships, with many even receiving living allowances.4

Liberated from a significant financial burden, and increasingly critical of existing social structures, students experimented more freely with alternative ways of living, from pharmacologically enhanced, free-love lifestyles and the refusal of social conventions, to collective protest and subversive politics (against a smorgasbord of perceived injustices including racism, sexism and the nuclear brinkmanship of Cold War diplomacy). Many of those counter-cultural concerns seem prescient of current preoccupations with alternative forms of community, the natural environment and the impact of technology. However, principles such as sustainability, networking, participation and information sharing were more connected with radical political action than with the mainstream, as they are today.

By the early 1970s social and environmental activism was also emerging internationally in the architecture profession and academy. (The Environmental Design Research Association, which came out of a 1968 design conference at MIT, was a strong advocate for “social architecture,” before later adopting a more conservative agenda.) The intertwining of social and environmental agendas at this time was typical, particularly in a political context. For example, in Sydney the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation, in alliance with sections of the student movement, including students and supportive staff from The University of Sydney’s Faculty of Architecture, instituted the famous green bans that blurred social and environmental boundaries.5 The Builders Labourers Federation employed the remarkably effective strategy of refusing to work on specific building sites in order to achieve ends that included securing the rights of a homosexual university student, protecting open space with ecological or public value from development, preventing the demolition of housing stock occupied by the urban poor, preserving architectural heritage and securing Indigenous land rights.

The Australian student architecture congresses leading up to 1972 also point to students’ shifting aspirations for what architecture could be and do. Attendance sometimes outstripped that of the national professional conferences and the guest speakers were more radical and diverse. They included Buckminster Fuller, Cedric Price, Dennis Crompton (Archigram), Christopher Alexander and Aldo van Eyck (Team 10).6

By 1972, amid the University of Sydney student activism, the social and environmental agency of architecture was being reconsidered. Students and some staff from the Faculty of Architecture had become extremely dissatisfied with what they perceived as a narrow and inflexible architectural curriculum – technocratic and monolithic. The desire to diversify the curriculum and legitimize activities such as the Art Workshop classes as units of study can also be seen as reflecting broader tensions in architecture during the 1970s. These were particularly between disciplinary models asserting autonomy and those emphasizing its ties with other disciplines. As the received models of modernist functionalism eroded, architectural education struggled with the extent to which it should train students to engage with architecture as environmental design (contingent on social, economic, political and scientific contexts) or as a distinctive, autonomous practice whose knowledge base lay within its own historical objects. Appropriate to the times, the students at The University of Sydney went on strike, refusing to attend classes.

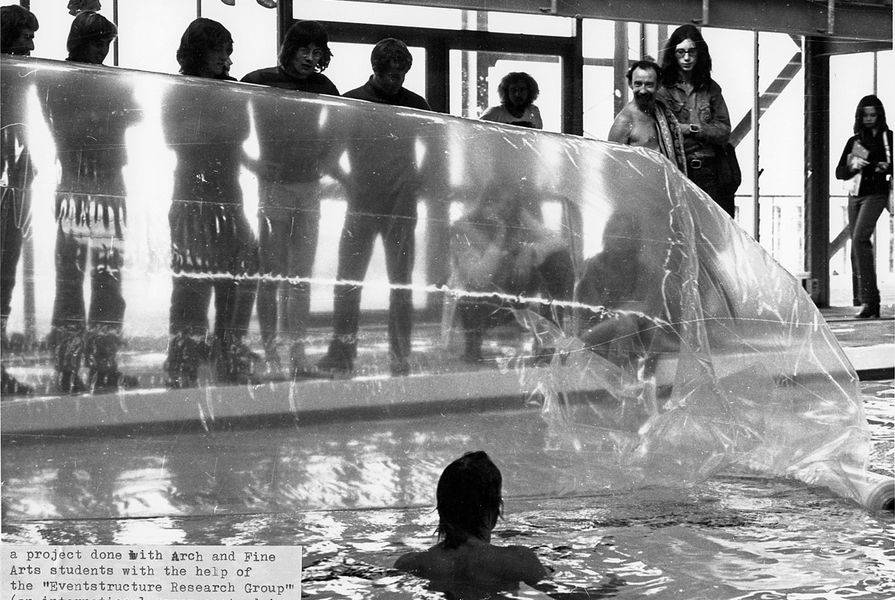

Following negotiations with the dean, a new curriculum was developed, intended to allow the opportunity for both diversity and depth of architectural education. A more open model, it fostered experiments with self-assessment and the introduction of an independent research project (one subsequent “thesis” was the construction and operation of an Indonesian restaurant on campus).7 Architecture students and staff more openly pursued educational projects that addressed pressing social and environmental issues.

One of the most notorious projects to emerge from these new conditions ran from approximately 1974 to 1978. The Autonomous House – a bricolage of alternative technologies on the lawn beside the architecture faculty – was one of the earliest experiments of its kind in the world. Designed and constructed by architecture students using recycled and donated materials, it employed passive solar strategies (including a Trombe beer-bottle wall), and ambitiously aimed to generate its own power, harvest and heat its own water, produce its own food supply and recycle all of its waste (sadly, biogas production was thwarted by Council’s refusal to allow pigs on campus).

The historical and cultural context of 2012 and that of 1972 are utterly different, but architecture’s agency is again being rethought, this time in the shadow of global financial crises, climate change and intensifying urbanization. An interest in more sustainable, socially engaged practices is evident, as is a search for concepts and terms to sustain and legitimize those practices. These changes can be seen in Australia, for example, in the theme for the 2012 Australian exhibition at the Venice Architecture Biennale – Formations: New Practices in Australian Architecture.

Many of the ideas and practices currently being explored resonate with alternative, and often marginal, architectural experiments and polemics of the 1960s and 1970s. But the understanding of what it is to be a student activist or an architectural activist has obviously shifted dramatically since 1972. As a student, going on strike would now seem an improbable course of action – time has become a scarce resource and student activism must be tactical and system savvy. Likewise, architectural activism looks dramatically different. Symptomatic of a resurgence of interest in activist practices, as well the differences in their more recent forms, is the wealth of accompanying publications. Exhibitions at The Canadian Center for Architecture in 2008 (Actions: What You Can Do With the City) and the New York Museum of Modern Art in 2010 (Small Scale, Big Change: New Architectures of Social Engagement) captured some of this, and suggested architecture’s radical possibilities now arrive through an expanded practice where architects engage in new kinds of collaboration, use new tools and interact with the world through new regimes of public and social media.

In Australia the experimental, subversive projects, conceptual work, pedagogical initiatives, exhibitions and publications of that earlier period – signified here by the 1972 strike –remain largely unexamined: the stuff of local mythology. However, the excavation of those initiatives might significantly reshape understanding of postmodern Australian architectural history. We suggest there is a need to trace the alternatives they projected, not in order to reclaim them for the present, but to consider the dialogue with history as a site of potentiality.

Glen Hill is an associate professor and Lee Stickells is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Architecture, Design and Planning at The University of Sydney. They would both welcome more information about the student strike of 1972 and architectural activism of the period more generally.

This article was originally published as part of a dossier in the March 2012 issue of Architecture Australia that discussed whether the architecture profession was losing ground.

1. Jennifer Taylor, “In Memoriam: Professor RN (Peter) Johnson 1923 — 2003,” Archetype, 10 August 2003, 8.

2. Thomas A. Dutton, Reconstructing architecture: critical discourses and social practices (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

3. Alan Barcan, “Student activists at Sydney University 1960—1967: a problem of interpretation,” History of Education Review, vol 36 no 1, 2007, 62.

4. ibid., 62.

5. Colin James, interview with Glen Hill, 11 November 2011.

6. Byron Kinnaird and Barnaby Bennett (eds), Congress Book V1.0 (Melbourne: Freerange Press, 2011).

7. Colin James, taped interview with Therese Kenyon, 9 August 1994.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 22 Jun 2012

Words:

Lee Stickells,

Glen Hill

Images:

Courtesy of The University of Sydney Archives (G3_224_2132).

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2012