MANAGING RISK

In the tussle to win projects, architectural practices are assuming greater risk burdens all the time. This threatens the ongoing viability of the profession as a whole. Anthony Kearn, National Risk Manager at RAIA Professional Services, reflects on how a

“The answer is simple.

You deserve to be paid for what you do. The drawings are what your client wants so don’t release them until the money is in the bank.”

Sitting in the elegance of the Sydney Opera House at the 2005 RAIA National Architecture Awards I was again filled with awe at the ability of architects to transform our perception of space using their palette of common materials. I was also struck by the number of award-winning architects who ascribed at least part of their success to the quality of the relationship with their clients, with terms such as “open-minded”, “visionary” and “forward-thinking” receiving repeated airings during the night.

Attending such functions reminds me of what drew me to my job as a risk manager with RAIA Professional Risk Services: a love of architecture and a desire to help architects do their job. To me, architects are the custodians of our cultural heritage and they add immeasurably to our quality of life. However, too often I encounter relationships between architects and their clients that have not fared as well as those referred to in the acceptance speeches on the evening of 27 October last.

Relationships based on dissatisfaction, suspicion and conflict that rarely, if ever, result in awardwinning buildings.

Constant exposure to the challenges facing architects means I often reflect on the causes of such challenges. Not the immediate causes such as negligent design, inadequate documentation or late delivery of services, but more fundamental issues that can so easily result in chronic relationship problems between architects and other participants in the construction industry. It is these fundamental relationship issues that I want to explore here.

My aim in offering these reflections is not to inflame or dishearten, but rather to stimulate discussion and comment in the interests of protecting the future of Australian architecture.

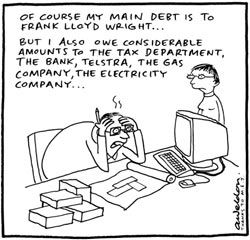

Picture the following scene: Pete is a director of a large commercial architectural practice and he is having a bad week (one of many recently). Two of his senior associates have given notice that they are leaving to set up their own practice. His accountant has just informed him that yet another invoice on his largest job has gone unpaid, bringing the total of outstanding fees on that project alone to over one million dollars. His staff are at breaking point, having worked day and night for weeks to answer the flood of requests for information following novation to the contractor. In general, Pete’s debt profile is running at an average of 100 days and the principal topic on the agenda of the last three directors’ meetings has been the need to increase marketing due to a dearth of new business.

Pete is on his way to a meeting with a prospective client who is considering offering the practice a large commercial project. They are renowned as heavy hitters in the industry, but Pete is sure that he can make the relationship work even though he has had to drop his fee to one per cent in order to secure the job. The purpose of the meeting is to discuss the consultancy agreement that contains many terms that Pete’s insurer and solicitor have advised him to amend.

Unwittingly, Pete has handed his client an enormous amount of commercial leverage and the chances of him obtaining any amendment to the consultancy agreement are negligible. Thus, rather than remedy his situation, he will expose the practice to increased risk and may significantly worsen his debt and staff motivation problems.

Further, the relationship that Pete is embarking on has a high probability of ending in claims and litigation. So, how can Pete dig himself out of this quagmire? My first piece of advice to Pete is “own the problem”.

This is a fictional story. However, it is based in reality. Increasingly, I encounter senior architects who are frustrated. They feel at the mercy of the property development juggernaut, seemingly powerless to even negotiate the terms of their engagement. They feel undermined by fellow architects who insist on undercutting them and let down by their Institute for failing to address the problems of fees and risk transfer in the construction industry.

While some of the problems raised in the above scenario are external in origin, internal business management issues can significantly amplify their impact on practices. Issues such as staff retention, debt management, negotiation techniques and leadership are often overlooked in the day-to-day challenges of practice and their impact can be insidious. I wish to discuss two of these issues: debt management and staff retention. From a financial perspective, law firms and architectural practices have a lot in common. They rely upon intellectual capital for income, they issue progressive invoices for services already provided (work in progress) and they are asset poor. The combination of these features means that, to an architectural practice (as to a law firm), the two most important things are the management of debt and the retention of key technical staff. Many of the architectural practices I have had contact with in the context of claims and risk management have chronic problems in these key areas. I am reminded of a deceptively simple piece of advice given to me by the first lawyer I ever worked for. He said, “Money isn’t money until it is in your hand.” With respect to debt management, the problem with so many professionals is an almost pathological aversion to talking about money and to assuming ownership of debt and responsibility for its recovery. This fits well with the approach of many in the construction industry who will withhold payment until they are asked. Thus the dance begins. The developer is desperate to get the DA in order to get finance and if possible will wait until novation and seek to avoid paying for design at all, while the architect is happy to continue working without being paid. To me the answer is simple. You deserve to be paid for what you do and the drawings are what your client wants so don’t release them until the money is in the bank. The issue of staff retention is a little harder to resolve. Obviously, the primary problem with the loss of key staff is the drain of intellectual capital and the concentration of responsibility on directors and junior staff in a way that often results in errors and duplication of effort. However, in leaving to establish their own practices young architects may also play a role in compromising the sustainability of architectural practice as a whole. These architects will often compete directly with the practice they have left and, given that they do not have the same reputation as their former employer, their principal bargaining chip will usually be price. This has the effect of reducing the market rate for all architects and directly affects the resources that architectural practices can afford to dedicate to increasingly complex client requirements. Thus, the problem is perpetuated and the risk profiles of all practices suffer as everyone struggles to compete with increasingly unmanageable margins. This is not to say that the problems associated with staff retention are entirely attributable to those leaving the larger practices. Many of these architects have good reasons for leaving – a lack of empowerment (both commercial and creative), poor succession planning, meagre remuneration packages and questionable job security are often cited as chronic problems within the profession. Of course, these are complex issues and I don’t have all the answers; however, I am concerned that, until the architectural profession addresses them in a meaningful way, the construction industry will continue to exploit the commercial vulnerability of architects in order to transfer an ever-increasing risk burden in the form of onerous consultancy deeds, unqualified certificates and aggressive procurement practices that will only be realized in the next generation of claims. To my mind, at least part of the answer lies in education. In assisting larger practices with risk management, it is apparent to me that junior architects are poorly prepared for the commercial realities of practice and, unless they are lucky (or studied commerce at university), this omission in their education is unlikely to be remedied before they reach positions of significant responsibility. In these positions they will be required to make decisions that may have major risk implications for the practice, but they are rarely provided with the appropriate tools to make such decisions. Even a cursory review of courses available to architects suggests that the need for seminars on design innovations and important topics such as planning, ecologically sustainable design and occupational health and safety is more than adequately satisfied by the current stock of professional development seminars. However, following graduation from university, architects are rarely exposed to formal courses on issues such as manage architectural practices. Alternatively, such a course could form part of a preparatory process leading to promotion within larger practices for those architects who choose such a career path. I am aware that some will question the need to interfere with the natural order of things by undermining the commercial leverage of practices that have already adopted sound commercial practices. However, the profession as a whole ultimately pays for the indiscretions of the commercially challenged. Therefore it is in everyone’s interests to raise the bar at least a little and return to competition based on true market differentiation. But it is important for all architects to realize that they are not alone in this challenge. You are surrounded by a network of other architects, many of whom will have faced similar issues in their practising lives and who would be more than willing to assist you. But if cold-calling your colleagues is not your thing you could contact a Senior Counsellor, get registered, join the practice committee, enrol in an MBA. In short, participate and support each other in shifting the risk burden back to a sustainable level and ensuring that architects are able to continue their valuable contribution to our cultural heritage across all aspects of construction. ANTHONY KEARN IS NATIONAL RISK MANAGER FOR RAIA PROFESSIONAL RISK SERVICES. FURTHER INFORMATIONRAIA Professional Risk Services Anthony Kearns National Manager, Risk Management RAIA Professional Risk Services T 02 9957 5700 F 02 9957 5722 E anthony.kearns@ raiains.com.au or enquiries@raiains.com.au W www.raiains.com.auContinuing Education RAIA National Continuing Education Program “Risky Business: Project Cost Risk Management”. All capital cities. T 03 9650 2477 E ce@raia.com.au W www.architecture. com.au/CEprogramsOther contacts Institute of Arbitrators and Mediators Australia T 03 9607 6908 E national@iama.org.au W www.iama.org.au