Charles Wright of Charles Wright Architects.

Image: Peter Bennetts

I met Charles Wright in 2008 during the Queensland Regional Architecture Awards for Far North Queensland. I was the chair of the jury and (W)right House was an entry in the awards. I recall being impressed by the organization and confidence of a young man (well under forty) as he led us through an extraordinary house that decoded contemporary domestic tropical design, and abstracted the golden ratio to achieve a climate-responsive outcome with massive materials, complex geometries and a striking exterior form. Did I like it? As a Queensland-educated, self-described critical regionalist I was quite simply perplexed. This house worked really well, was sustainable and looked extraordinary, but it did not recall anything I had come to understand as Queensland design. Six years later, it is precisely these characteristics of Charles Wright’s work that are putting Far North Queensland on national and international architecture maps. Every project Charles completes challenges and/or reinterprets the expected solution to a problem, and this is what is fantastic about his work.

Charles Wright Architects (CWA) was established in 2004 and is now a practice with ten staff in two locations: Melbourne and Port Douglas. Architecture is Charles’ second profession. He first trained in fine art as a sculptor and painter and then in his early twenties studied architecture at RMIT University in Melbourne. His fine art training is clearly evident in the sculptural and compositional qualities of his work – bold, simple, striking and well balanced. CWA has won awards for many of its residential projects, but the practice has also built a reputation for designing striking public and educational facilities such as the Cairns Botanic Gardens Visitors Centre and the Malanda Falls Visitors Centre. CWA has a number of commercial and multi-residential projects underway across the country.

Charles Wright Architects was established in 2004 and is now a practice with ten staff in two locations: Melbourne (pictured) and Port Douglas.

Image: Peter Bennetts

When I met with Charles for this article, he stated that he loves working in the tropics because there are few environments so free and conducive to expression and creativity – expressions of bulk and strength to withstand cyclonic conditions coupled with openness and connectivity with the glorious natural environment. These principles are captured in all of his north Queensland projects. His own house, which he designed, is on 4.5 acres at Oak Beach. It is elegantly brutal and simple with polished concrete floors, open (and screened) blockwork walls, and circulation spaces on the perimeter of the house. In many of Charles’ projects you are forced outside or onto a transitional verandah or under eaves to move from space to space. The house is wedged against a World Heritage-listed rainforest at the rear of the site and nestles between rock, the rainforest and the ocean view. He shares his home with his wife Justine, who is active in many areas of CWA, and their three children.

(-) Glass House (2012): Referencing Philip Johnson’s International Style Glass House, minus the glass.

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

In comparison, CWA’s (-) Glass House is set on a suburban house block in Cairns with no view of sea or mountains. The house was designed for a couple with adult children for whom accessibility and sustainability were imperative. It is an exceptionally innovative solution to tropical, accessible living in a regular urban environment. The house derives privacy and security from fencing, screening and its lush garden – not from lockable doors and windows. There is a clear hierarchy of space, from a fully enclosed media and library room to the kitchen and dining spaces, which are only enclosed by the floor and roof. The (-) Glass House offers only minor mediation and control of the natural environment for those spaces and activities that can cope with being outside. This house offers a real alternative typology in tropical domestic design.

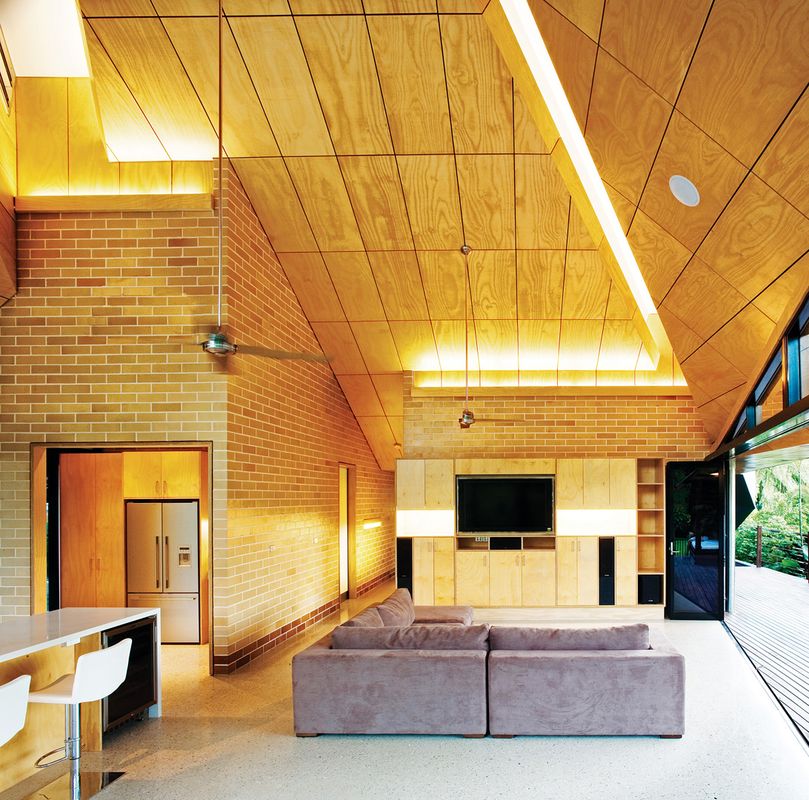

A clever alteration and addition that was completed on a tight budget is CWA’s Re-Newell Beach House. Re-Newell is a good example of how CWA can reinterpret a client’s simple brief for a kitchen and a deck to deliver something unexpected. The original dwelling was a modest fibro beach house, and from the street remains so. This belies its renewed reality, in which it has an extremely generous living area with clean, warm finishes and floor-to-ceiling bi-fold doors that allow uninterrupted sea views and breezes.

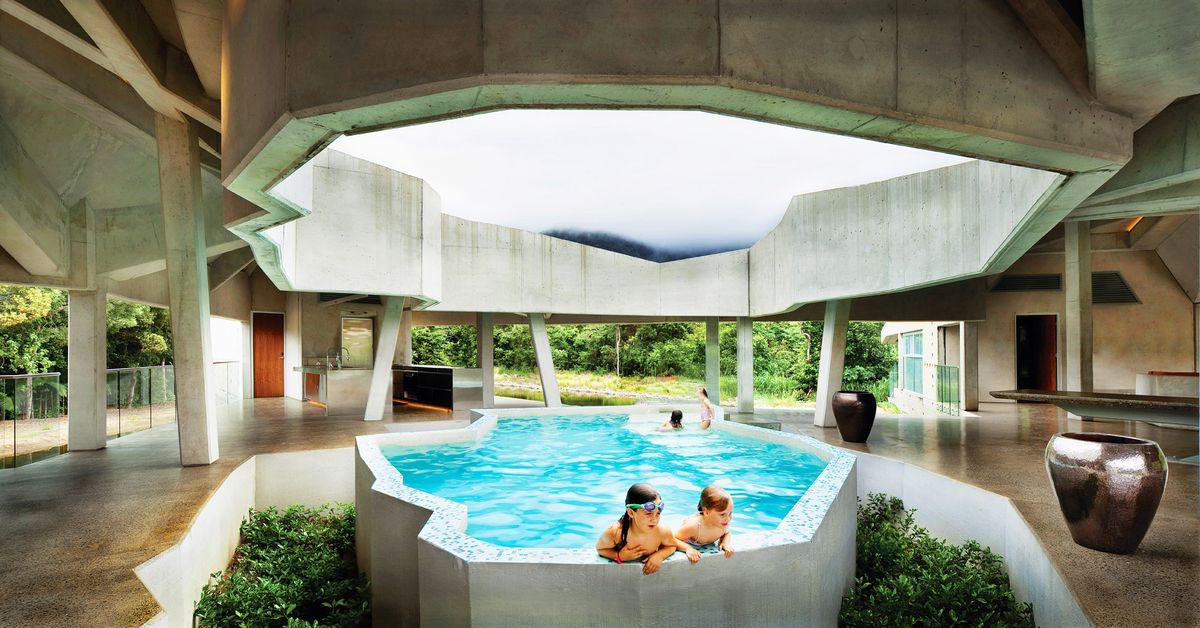

Stamp House (2013): A sustainable dwelling in its own private lake/wetland.

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

The theme of openness and sculptural composition is at its pinnacle in the Stamp House, which was the winner of the Robin Dods Award for Residential Architecture in 2014. The Stamp House is designed as a sustainable dwelling in its own private lake/wetland in the Daintree Rainforest region of Far North Queensland. The spectacular sculptural form of the dwelling is a response to the need for resilience to, and durability for, cyclones and storm surge events. The Stamp House is carbon neutral in operation. All energy is renewable, provided by a large photovoltaic array and battery storage, and the entire roof area is used to harvest rainwater into a 250,000-litre in-ground tank integrated with all hydraulic systems. The Stamp House elicits contradictory responses from the public and other professionals in design industries. It is a controversial work because it blatantly questions how we make residential architecture in the tropics. The Stamp House is confronting because it reflects an apocalyptic future in which the climate is a tyrannous force to be withstood, and this is the kind of housing that might well survive.

Charles is extremely optimistic and pragmatic, he exudes love of his profession and craft, and his energy is contagious. He denies being courageous, even though his work is clearly brave and innovative. Charles is not shackled by the vernacular (unless you consider our recent concrete block history post-WW II vernacular). His work is seeking new identities and new paths for tropical architecture with climate change in mind, and this is extremely refreshing. It is helping to build an international architectural profile in a region that is more recognized for its natural beauty than its built environment, and it is igniting renewed debate and thinking around tropical architecture.

Source

People

Published online: 19 Mar 2015

Words:

Shaneen Fantin

Images:

Patrick Bingham-Hall,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Houses, October 2014