The principal challenge facing interior designers choosing to work in the emerging field of school interior design is to develop physical learning environments that strike an effective balance between purposeful design and flexibility. This article discusses the contribution of interior designer Mary Featherston’s school design practice towards achieving that balance.

Mary Featherston.

Image: Belinda McSween

A growing body of brain science and education research that describes learning as social, situational and experiential has renewed interest in constructivist pedagogies and inspired a shift in mainstream education away from traditional methods of transmitting information towards collaborative and experience-based learning. The resulting wave of international education reform has been accompanied by political enthusiasm for the transformative power of architecture. Much less attention has been paid to the influence of interior design in schools, which until recently has been the domain of teachers. Now school communities are beginning to collaborate with interior design professionals because research exploring the interrelationship between pedagogy and space has identified the importance of the physical environment in providing multiple contexts for learning. Consequently, school interior design is emerging as a discrete sub-discipline of interior design practice.

In school architecture and interior design, education reform is being expressed as a rejection of teacher-centred conventional classrooms in favour of physically complex learner-centred environments, often referred to as “learning neighbourhoods” or “nodes,” each housing a large student community and a team of teachers. Surrounded by a debate about flexibility, different models have been proposed for learning neighbourhoods ranging from flexible open plan spaces to purposefully designed environments like those developed by Featherston. Providing appropriate structure and services avoids the need for teachers to continually reconstruct the physical environment and also provides sufficient flexibility so that they can shape the environment to suit their particular pedagogical aims.

Over the course of many design collaborations with innovative educators in preschool, primary and secondary schools, Featherston has developed collaborative design processes for working with school communities. But what is most significant about her school design practice is that it has established an interior design language for contemporary learning neighbourhoods and design patterns for a range of purposeful learning settings. Her design patterns are akin to those described by Alexander et al.1 in that the specific interpretation of each pattern in response to a school’s philosophy and vision gives it a unique character, so that no two schools will be the same. Similarly, within a school the same pattern may be interpreted differently in response to the specific functional and psychological needs of the children in each neighbourhood.

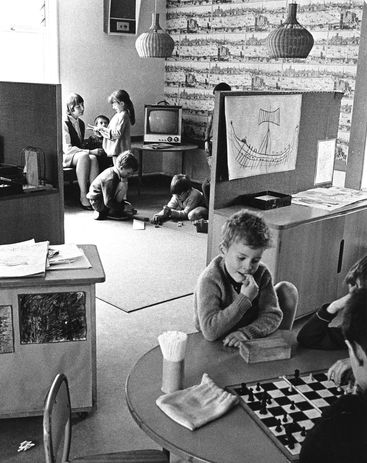

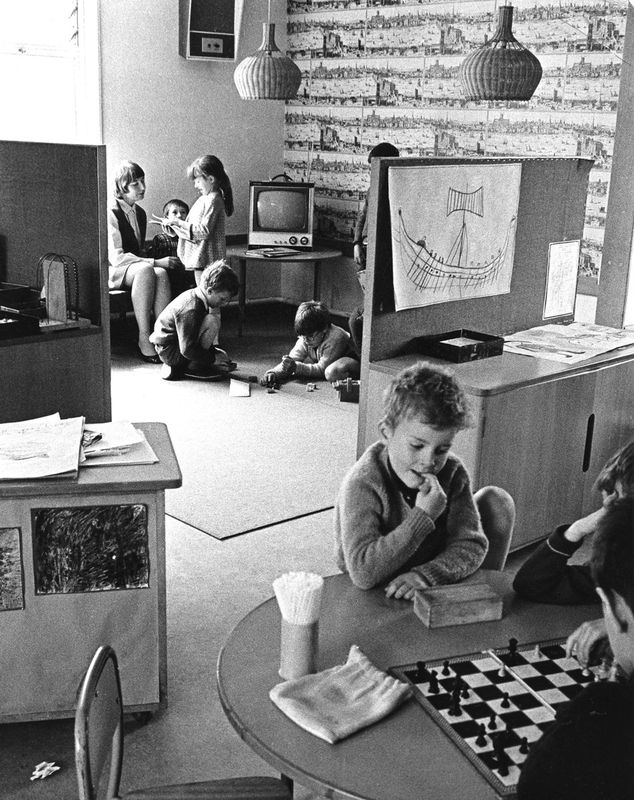

Eveline Lowe Primary in London, designed by David and Mary Medd between 1964 and 1966.

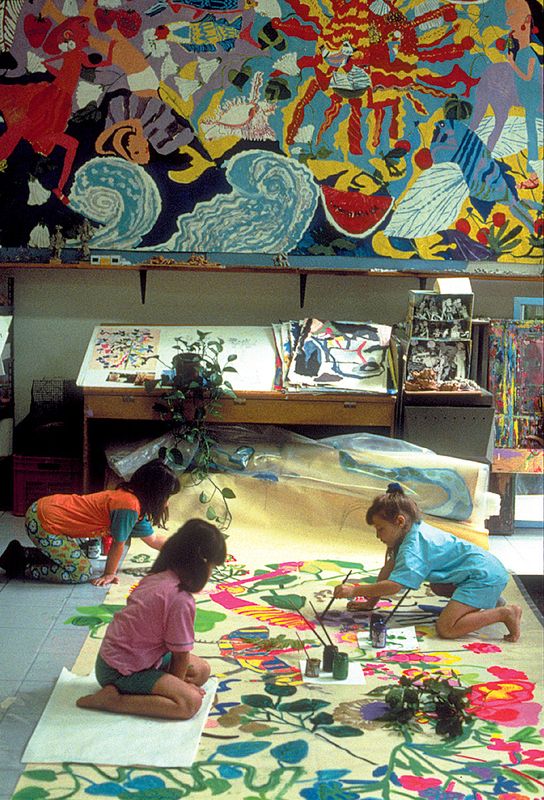

Featherston’s vision of learning neighbourhoods as holistic, democratic and convivial environments2 comprising multiple purposefully designed learning settings is similar to the approach taken by David and Mary Medd when designing primary schools in London in the 1960s. The Medds believed that in order to “combine exploration with achievement” at school “the homogenous character of the conventional classroom had to be destroyed” and replaced by “richness and variety of environment, with different kinds of spaces: a complex of interrelated opportunities, with differences in scale, equipment, finishes, lighting, colour, acoustic quality and general character.”3 The total of these design decisions (the interior of each setting) gives children, teachers and visitors environmental cues for activity and behaviour. Featherston’s diverse range of learning settings is designed to encourage students to use multiple intelligences4 and expressive languages.5 The adjacencies between settings are designed to promote the transfer of skills and understanding from one setting to another. Specialist facilities such as wet areas, performance spaces and ICT are integrated into the neighbourhoods so students are not constrained by timetabled access to a separate art room, drama room or computer lab.

Like the Medds, Featherston introduced ideas about physical learning environments,6 usually associated with progressive education, to mainstream schools. Her purposeful design is informed by the failure of Australia’s open area schools in the 1970s that were unsuccessful, in part, because teachers struggled to implement pedagogical change in environments that were characterized by large areas of uncommitted space and moveable furniture. The challenge for designers working in this field is to work closely with communities to develop learning environments that balance purposeful design with flexibility, so that students and teachers have easy access to tools, resources and technologies when and where they need them, in a learning neighbourhood that they can manipulate to suit their changing needs.

Acknowledgements

This article draws on research that was supported under Australian Research Council’s Linkage Projects funding scheme (project number LP0776578), “The School: Designing a dynamic venue for the new knowledge environment.”

Chief investigators—Dr Denise Whitehouse and Dr Deirdre Barron; Partner investigator—Mary Featherston; Researcher—Kellee Frith.

Industry partners—Bialik College, the Victorian Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and Woods Furniture Pty Ltd.

1. C. Alexander, S. Ishikawa, M. Silverstein, M. Jacobson, I. Fiksdahl-King & S. Angel, A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction (Oxford University Press: 1977).

2. M. Featherston, “Inside-out project,” Mary Featherston Design, www.featherston.com.au/inside-out.html, 2006.

3. D. Medd & M. Medd “Designing Primary Schools,” in National Froebel Foundation (Great Britain), Designing Primary Schools (National Froebel Foundation: 1972), 9.

4. H. Gardner, Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice (Basic Books: 1993).

5. C. Edwards, L. Gandini & G. Forman, The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach to Early Childhood Education (Ablex Publishing Corporation: 1993).

6. K. Frith & D. Whitehouse, “Designing Learning Spaces that Work: A Case for the Importance of History,” History of Education Review, vol. 38, no. 2, (2009): 94–108.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 1 Sep 2011

Words:

Kellee Frith

Images:

Belinda McSween,

Dianna Snape,

Peter Clarke,

© Preschools and Infant-toddler Centres, Istituzione of the Municipality of Reggio Emilia

Issue

Artichoke, June 2011