It’s fitting for a house that hatched a revolution to be somewhat revolutionary itself. Pymble House by Russell Jack of Allen Jack and Cottier is a heroic Sydney School project that has been something of a well-kept secret between the neighbours, the sports star who commissioned it and the architect who has occupied it for the last quarter of a century.

When the house was competed in 1972, Allen Jack and Cottier was asked by its owner, Geoffrey Forsaith, not to publish it. In the late 1970s, Forsaith, a former cricket player and friend of Kerry Packer, headed up Packer’s breakaway World Series Cricket. As he was team manager, Forsaith’s Pymble House became a stage for the secret deals and wild parties that ushered in the controversial new series. That story was told in a 2012 television series, Howzat! Kerry Packer’s War, and more recently in the book Cricket Outlaws: Inside Kerry Packer’s Revolution, written by another former Packer lieutenant, Austin Robertson.

The house consists of two wings that form an L-shape around the swimming pool.

Image: Brett Boardman

A party house it may have been, but that was not the brief to Russell Jack. Forsaith wanted a substantial family home with a large lap pool at its centre, for his daughters’ swimming training. “The pool was central to the brief, and central to our approach; the whole house was designed around it,” recalls Russell.

On a large battleaxe block, the house consists of two wings dividing living rooms from children’s bedrooms, forming an L-shape around the swimming pool. In the north-facing public wing are the kitchen, dining and living rooms, all opening to the pool area and the garden beyond. The split-level west wing contains a rumpus room and a double bedroom opening to the pool terrace and, on its lower side, two bedrooms, a guest suite and a bathroom facing the easterly front garden.

Tucked into the south-west corner, the main bedroom suite looks into a private courtyard garden off the kitchen. Backing onto this main suite, a large carport anchors the main entry and front garden, landscaped simply with hedges and lawn. The easterly, white-painted brick elevation is, in Russell’s view, the most ordinary and least successful part of the design, and the more recently planted hedges along the building are “a masterstroke that saves it.”

Split levels and clerestory openings allow for “superbly orchestrated sightlines that both reveal and conceal.”

Image: Brett Boardman

Inside, however, it is Sydney School organic modernism at its purest. The exposed structure and materials balance strength and lightness, with black-stained timber roof beams, spotted gum ceilings and whitewashed walls extending beyond the floor-to-ceiling windows and doors framed in Tasmanian oak. This is a deeply introverted house, opening to and reflecting on its setting with superbly orchestrated sightlines that both reveal and conceal. Moments of rich, reflective colour are reserved for the bathrooms – each tiled in a different shade of glass mosaics – while outside, the copper downpipes and guttering bear the green patina of age.

Though Pymble House is large, it clearly comes from an earlier, humbler predecessor, Russell’s own house, which he hand-built with his architect wife Pamela in 1956 in Wahroonga (see Houses 78). It shares the exposed timbers and whitewashed brick walls, the separation of public and private domains, the floor-to-ceiling doors and windows extending rooms out into the garden and the natural light and shade harnessed through passive solar design. And peerless craftsmanship.

As a young architectural graduate, Russell completed a grand tour of Europe, which led him to reject the “machined” international modernism of the 1950s, embracing instead local materials, climate and landscape for a more authentic architecture of place. He and others would develop the Sydney School language with raw materials uncommonly crafted, indoor/outdoor connections and exposed structural details. “Buildings should tell you what holds them up and how they’re put together,” says Russell.

The introverted house reveals little about its formal organization to the street.

Image: Brett Boardman

For current owner and architect, Malcolm Carver and his wife Wendy, the CEO of Lifeline Harbour to Hawkesbury, Pymble House has been the home where they raised three children and that they recently listed for sale. Malcolm retired in 2009 from his practice Scott Carver Architects and reflects on what the house has meant to him. “It’s been a great teacher to me, and I have treasured having all the original drawings; they’re so fastidiously detailed. It has been a joy for our family to live here, but now it’s time for us to move on.”

An aspect he particularly loves is the strong geometry of its walls and roof planes, especially as they align at a crucial interior juncture. Marrying the two wings of the house across a sloping site is a high, vaulted ceiling over the east wing corridor, which today serves as a long gallery for Malcolm’s landscape paintings and sketches. Since retirement Malcolm has become an architectural tour guide and artist, combining both his passions.

The impeccable condition of Pymble House owes much to Malcolm’s stewardship. In nearly twenty-five years of occupation, he has made only a few discreet alterations. One was to line a section of the roof pitch over the carport for a loft studio, now filled with architectural drawings and books from a lifetime in practice. Another was to replace the screened-in, all-wood kitchen with an open-plan arrangement of white benches and a breakfast nook. The final intervention was a pool cabana that Malcolm had been sketching for a while.

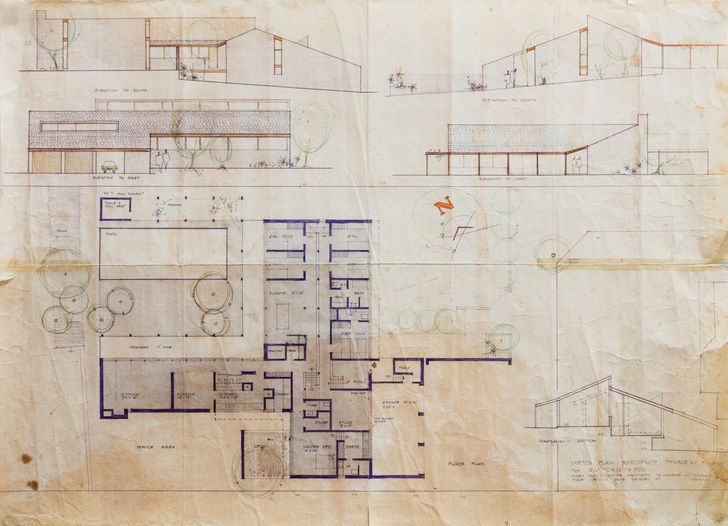

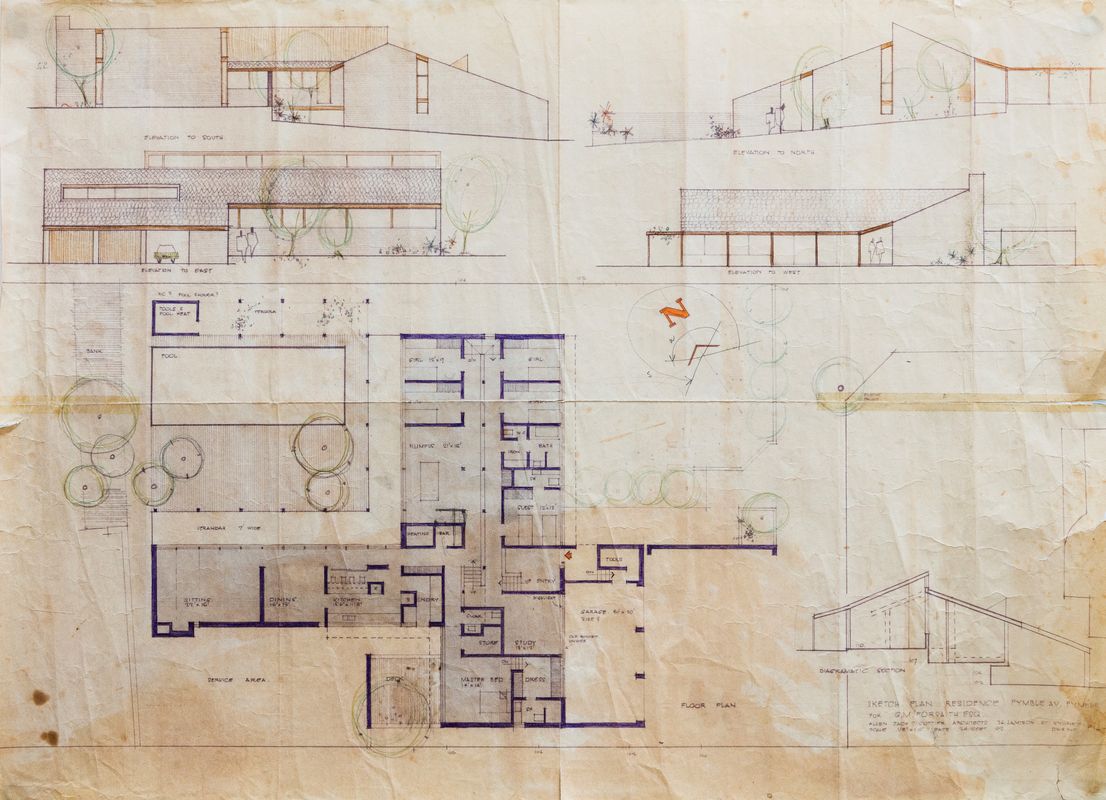

A sketch plan of Pymble House by Allen Jack and Cottier, dated 24 September 1969.

Russell, now in his nineties, was invited by Malcolm to revisit the house before it changes hands for only the second time in nearly five decades. He was delighted to hear about the notoriety of the house and to see how well it is preserved.

“The house was all about that play on levels and roof planes. It was exciting to see that split corridor and the way the roof frames line up over it. That was important – we worked a lot on getting that right. It was a good resolution and it still works,” Russell says, rejecting the idea of the roof as a grand gesture. “We were taught that form follows function. You weren’t designing a piece of sculpture, you were designing a building. It had to work, and you hoped it looked beautiful too. I still believe in that.”

Credits

- Project

- Pymble House

- Architect

- Allen Jack + Cottier Architects

Chippendale, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Consultants

-

Builder

CH & CR Ellis

Engineer Taylor Thomson Whitting (TTW)

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Source

Project

Published online: 13 Nov 2018

Words:

Peter Salhani

Images:

Brett Boardman

Issue

Houses, August 2018