The layperson on the jury is the most important judge,” Sean Godsell tells me over dinner after we have walked through, around and under his RMIT Design Hub building. He was referring to my recent involvement with the Australian Institute of Architects national awards. I had a slightly different understanding, having been on the road with my well-informed co-jurors for a fortnight, travelling thousands of miles and having some often heated discussion. At times I wished I had brought along Architecture for Dummies … or a loudhailer. But in essence I think Sean was suggesting that the “lay” person has an honest and intuitive understanding of a building, unmediated by the rhetoric of the discipline and unhampered by allegiances.

One thing I am certain of, after our architectural sojourn and my work inside buildings of culture. You need to be around and inside a building, feel a building, sense a building through your body and, in the best possible scenario, use a building to test its functional premise. Photos will not do, glamorous though they are for the portfolio.

This is especially true in these days of “skins.” Architecture as surface often dissipates to razzle-dazzle on the outside and mishmash or banality on the inside. The post-postmodern facade has at times made the interior insensible. This is elevated to a kind of spatial criminality in art museums and galleries, where, for some Freudian reason no doubt, architects want to “bring it up” to art. The metaphoric mouche and vivid vizard on the outside is supposed to make up for the impertinent impositions on display and its contents.

You forgive some things. Arken Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, for instance, is generally agreed to be hopeless for a hang, but is nevertheless a marvellous external and internal space – but better for design displays than art. Which brings me back to the start.

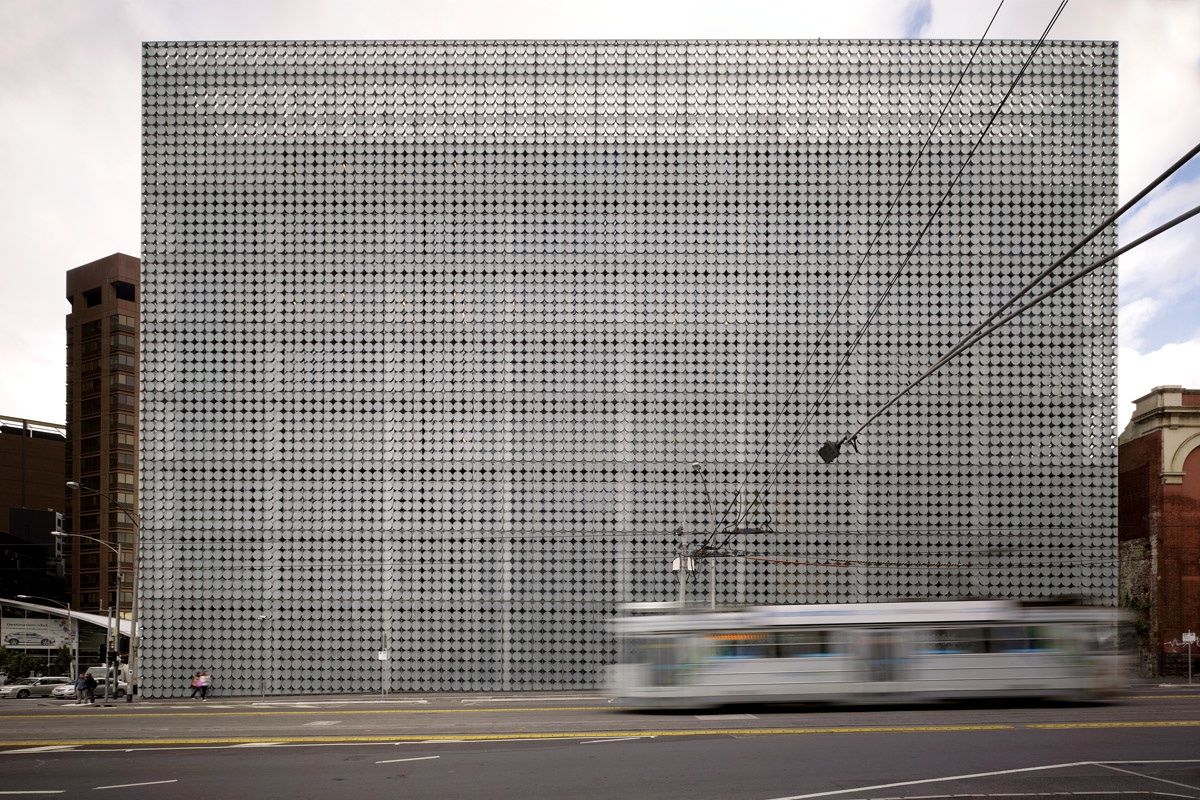

Sean Godsell’s building appears on its surface to be a clean and plain container. Its facade design of translucent discs with metal hooped holds remembers the kegs of beer that once were the business of the CUB Brewery site, but this is a metaphor made lightly, updated to the stylization of the screen, a part of Godsell’s own vocabulary and one for which he is renowned. This containment makes the building feel compact and neat, orderly and undemonstrative in the helter-skelter company of the buildings around it. With its external walls of discs, it is almost armadillo-like, a kind of samurai chest-plate-wearing building: a warrior structure with which Godsell attempts to save architecture from its unruly cousins, from itself.

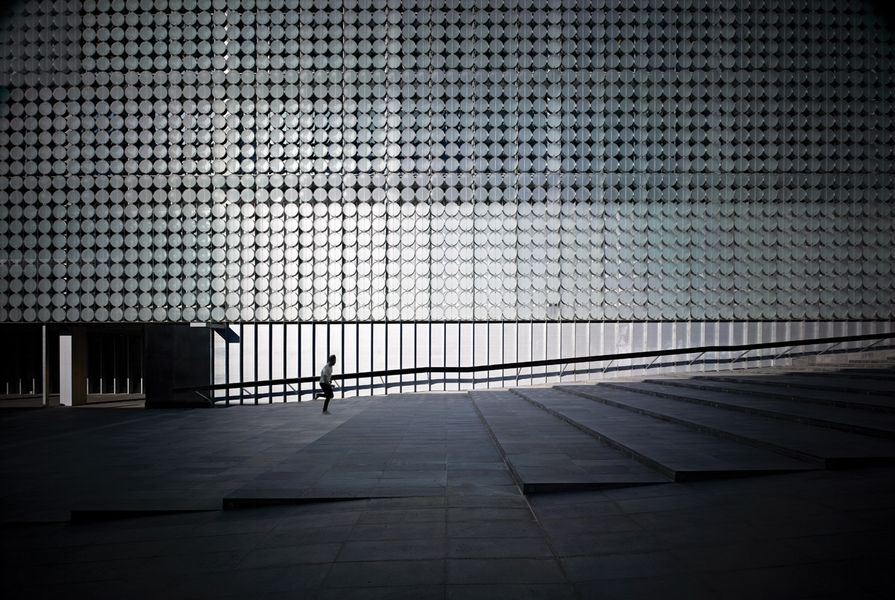

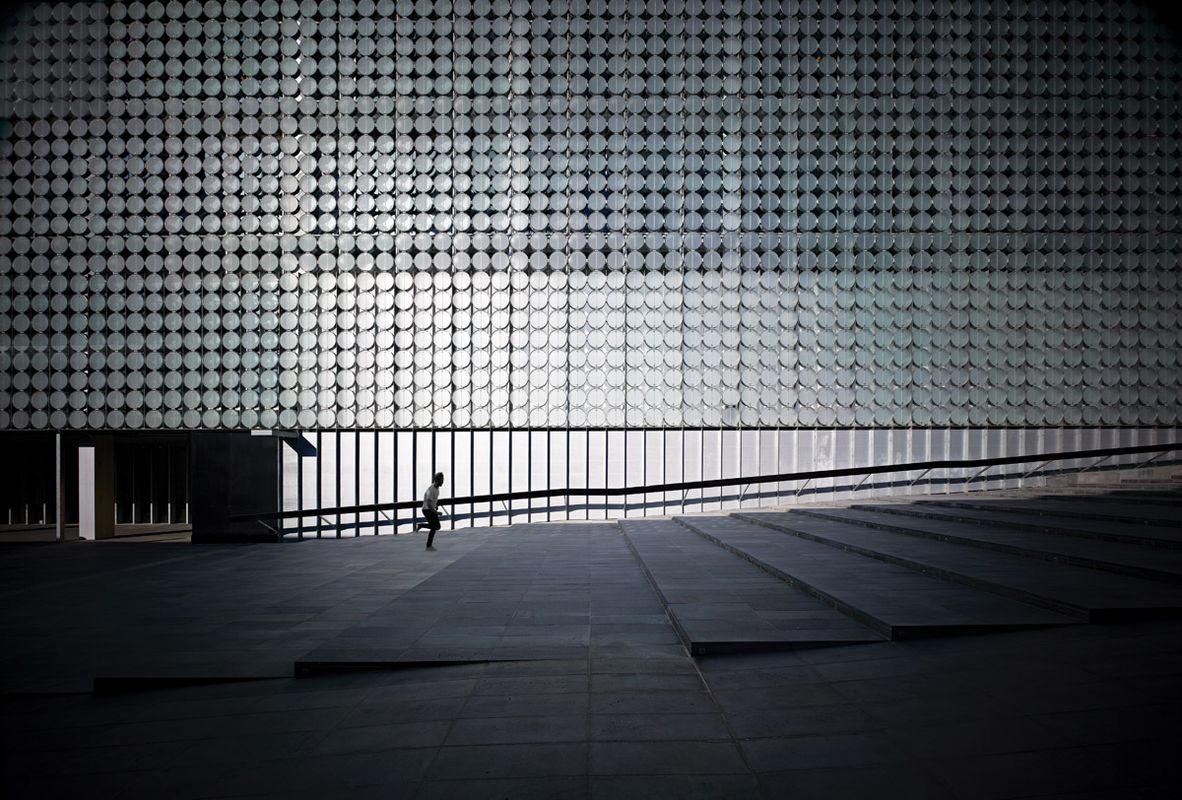

This containment is, of course, in the layperson’s assessment, a foil to conceal the spatial tactics Godsell employs inside his building. For all the restraint and modesty of the exterior, the interior is immodest and downright inflammatory in its heroic gestures determined to challenge the inhabitants. It is exciting and stimulating. You feel you are in the grip of an intellectual, metaphoric and material architect who has mastered his language of surface and space and those things that intercede.

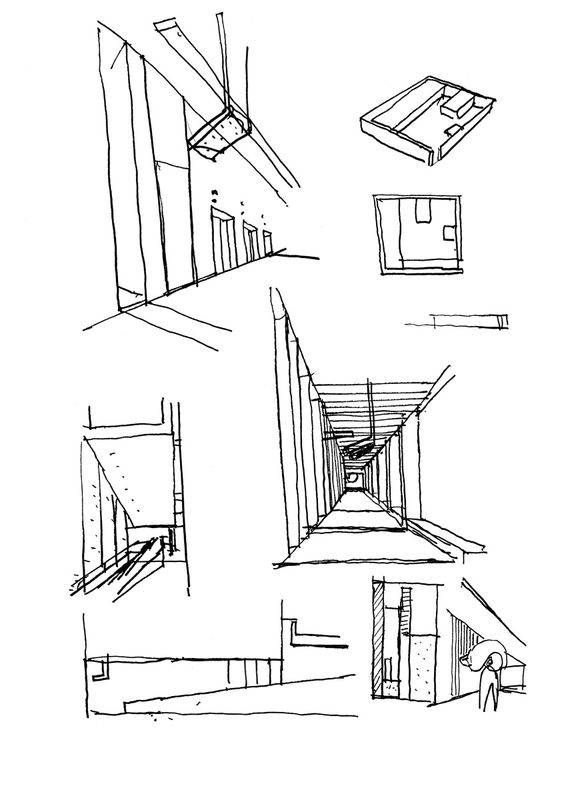

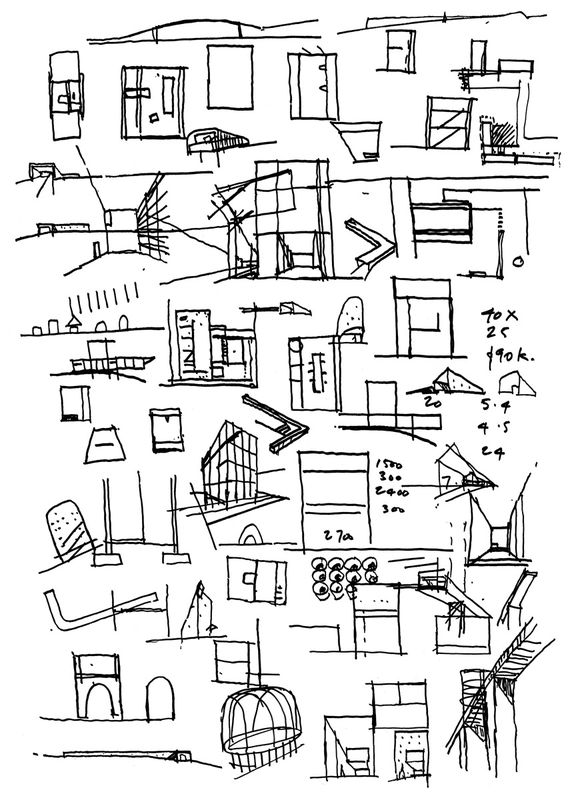

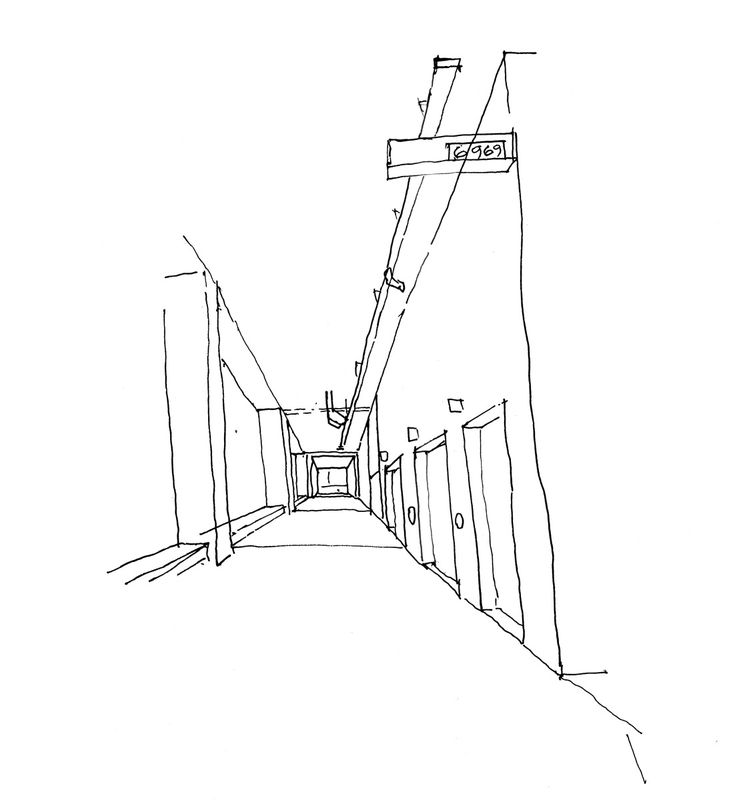

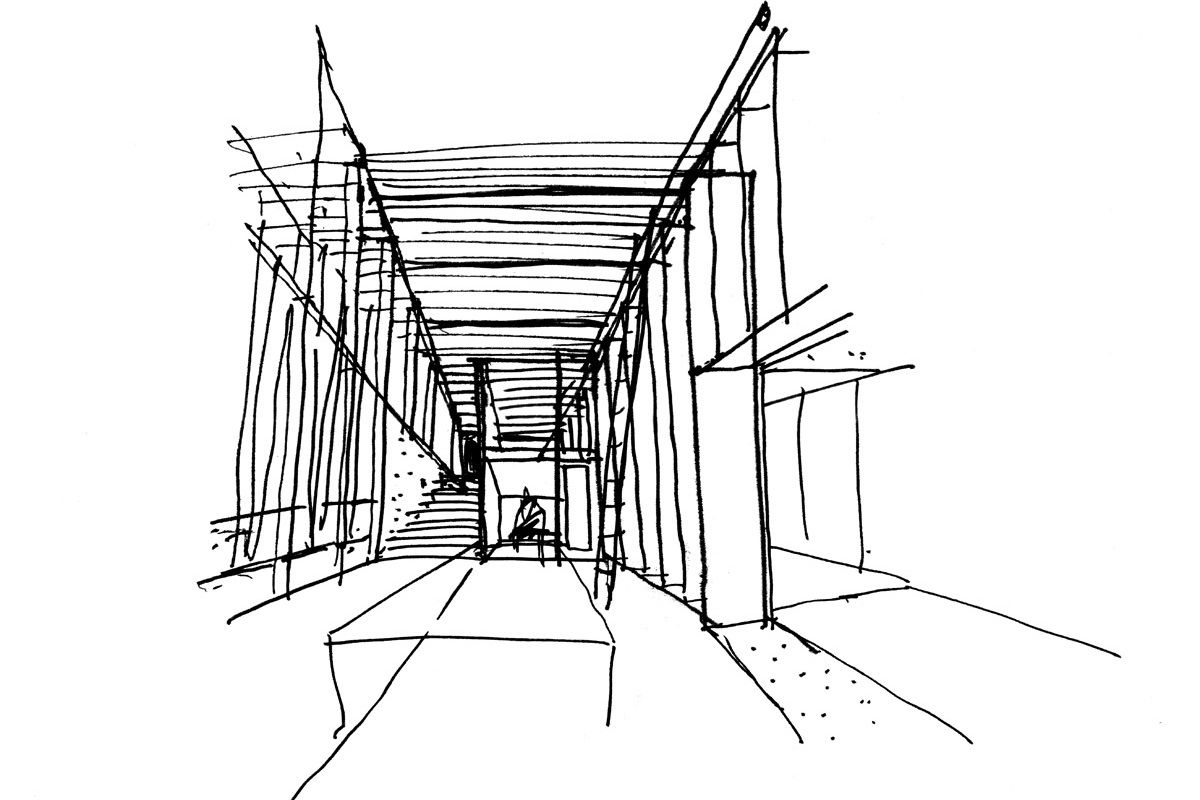

By some magic the interior feels larger than the external box. Godsell has used both linear and vertical gestures to expand space. Using a labyrinthine strategy, he sends the Hub-ists up and down and around, in and out of studios and wide corridors that become galleries and display halls.

His spaces for design research are deliberately open and available for adaptation. Wire sits in front of concrete walls, providing instant attachments so that designers can display their ideas and prototypical objects and drawings. Each floor awaits inhabitants who will bring their own needs into these democratic places. Here Godsell sends a dare out to fledgling professionals – determine your own environment, run amok if necessary. Here is a built world that speaks to the people who will build the world and design the things in it.

Undoubtedly his design responds to a brief calling for, I imagine, crosspollination and knowledge transfer and all those new innovation-speak phrases that still mean communication and looking. In Godsell’s Design Hub there is a deliberate and almost enforced need to engage with your cohabitants and their various creative nodes. The circulation of the interior pushes you to its passages and open spaces; the transparency of internal windows keeps information fluid and visible.

Good design does not come easy; it is often a Sisyphean task of trial and trial again. To emphasize the point Godsell has made his building make people work and be ambitious: in his spaces one feels still infantile. The architect makes his building metaphorically and literally tower above visitors cowering at the sheer verticality of doors elongated to extreme heights.

Godsell’s special exhibition spaces are lofty and capacious, daring a different approach to installation for design, so often neatly packed away into vitrines and popped on dainty plinths. Here, with the right curatorial vision, design can soar and push its way through space. These spaces are so large and dizzyingly vertiginous, you can barely understand how they find themselves in the tidy crucible of the building. The trick to this multiplying of space, I assume, lies in the use of round shapes externally, maze arrangements and broadness horizontally, and longitudinal structures internally.

Similarly, the internal staircase inserted into the middle, slicing from ground level to third, deranges your sense of the interior versus the exterior. This stair element of the architecture is sheer brilliance. The drama of the stair, squeezed between the seemingly vibrating walls created from a tight vertical metal pleating, disciplined from top to bottom, introduces a kind of Virgil and Dante, Heaven and Hell metaphor: it seems both pagan and ecclesiastical in statement.

On top of the building, Godsell provides an acropolis of pavilions and outdoor seating – as in ancient times, a city on the extremity – acknowledging and perhaps marking the axis between the Hub and the Shrine of Remembrance at the other end of Melbourne’s CBD. Godsell’s rooftop is a place of elevated splendour from which the designers can see the city and the place their work is destined for, the public realm and the environment. Pavilions lead one to another, providing meeting spaces and seminar rooms for lectures on the Mount. It is here that one glimpses the references to Godsell’s domestic work and smaller projects.

In the crypt of the building Godsell has made a place for the design archive. Here, as in churches, the relics of architecture will be catalogued and displayed – a world of models and plans and other ephemera that tell stories of miraculous deeds, saintly attempts and the lost buildings and objects in architecture and design’s story. When it is eventually activated with bequests and gifts of such work, it will be an amazing resource for both students and the public.

Between these top and bottom spaces are ramparts and circuitries that will be animated gradually by the works of students, with an opportunity for further displays, video walls and installations. Even the exterior can be adapted to light and image plays by using the translucent discs as a screen wall.

The Design Hub functions both as a building and as a declaration. In many ways Godsell’s Design Hub is a Gesamtkunstwerk – a synthesis of his theories, showing his ideals of design, architecture, spatial drama and materiality. Those qualities have made him famous for a disciplined approach that understands and follows every detail and has the intellectual and poetic capacity to raise the metaphoric out of material. Rigorous, uncompromising and beautiful, it is already iconic.

Credits

- Project

- RMIT Design Hub

- Architect

- Sean Godsell Architects

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Sean Godsell, Hayley Franklin, Chris Godsell, James Hampton, Raf Nespola, Peter Seear

- Architect

- Peddle Thorp Architects (Vic)

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Acoustic consultant

AECOM

Builder (base building) Watpac

Building surveyor Philip Chun & Associates

Facade Permasteelisa Group

Fitout Brookfield Multiplex

Hydraulics CJ Arms & Associates

Mechanical, electrical and environmental consultant Aurecon, AECOM

Project manager Aurecon

Quantity surveyor Davis Langdon

Services consultant AECOM

Services engineer AECOM

Structural consultant Felicetti

- Site Details

-

Location

Corner Victoria and Swanston Streets,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2012

Category Education, Public / cultural

Type Universities / colleges

- Client

-

Client name

RMIT University

Website rmit.edu.au

Source

Project

Published online: 21 May 2013

Words:

Juliana Engberg

Images:

Earl Carter

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2013