In his 1947 book Victorian Modern – the first real attempt at a history of Australian architecture – Robin Boyd championed Harold Desbrowe-Annear and Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin as pioneers of modernism in Melbourne. The suburb of Eaglemont had been fertile territory for both Desbrowe-Annear and the Griffins. As early as 1904, Desbrowe-Annear had prefigured the modern functionalist plan with his design for the Chadwick House, with its cellular but interlocking living spaces. Down the road, the Griffins continued the pursuit of the open plan in 1922 with Pholiota – an innovative, single-roomed house with surrounding alcoves, built for themselves, on one of two progressive garden suburb subdivisions that they’d designed and implemented during the war. At the time of Victorian Modern’s release, Boyd was not yet a household name and the architect had only built a handful of projects – one for his cousin Arthur, one for his young family in Camberwell, and another in Kew. But by constructing a historical lineage of local modernist projects, he was able to leverage the “new” architecture of postwar Melbourne and by extension his own practice.i

Deciduous creepers shade the glass wall at ground level during summer, and drop their leaves in wintertime to let the sun pour in.

Image: Sonia Mangiapane

Dentist and European émigré Victor Stone and music broadcaster Peggy Stone were young professionals with a penchant for the arts, who moved in the same circles as Boyd. By 1953 Boyd had established a name for himself through his directorship of the Small Homes Service and his regular column in The Age. Having moved to Melbourne after growing up in Sydney, Peggy longed for a house on a hill with a view, so the couple approached the architect to design their home on a block in Eaglemont, just between the two subdivisions designed by the Griffins: Glenard and Mount Eagle Estates.

Despite their limited means at the time, the couple didn’t want a Small Homes Service house. Boyd once described these off-the-plan designs as houses for “intelligent, vital people who cannot afford an original painting but buy a good reproduction.” ii Peggy’s grandfather was the esteemed Gothic architect William Wardell. “We knew a little bit about architecture,” Peggy told me in 2010. “You don’t just get a few bricks and someone who’ll stick them together for you.”

The Stones were familiar with the residential work of Boyd, Roy Grounds and John and Phyllis Murphy. “We ruled out Grounds straight away because he was so dictatorial: ‘And we’ll have this!’ you know, and, ‘We must do that!’ Robin at that stage was in the same position more or less as we were in ourselves … professional, starting out, but with young children,” Peggy said.

The extension, also designed by Robin Boyd, is the first thing encountered as you arrive at the house.

Image: Sonia Mangiapane

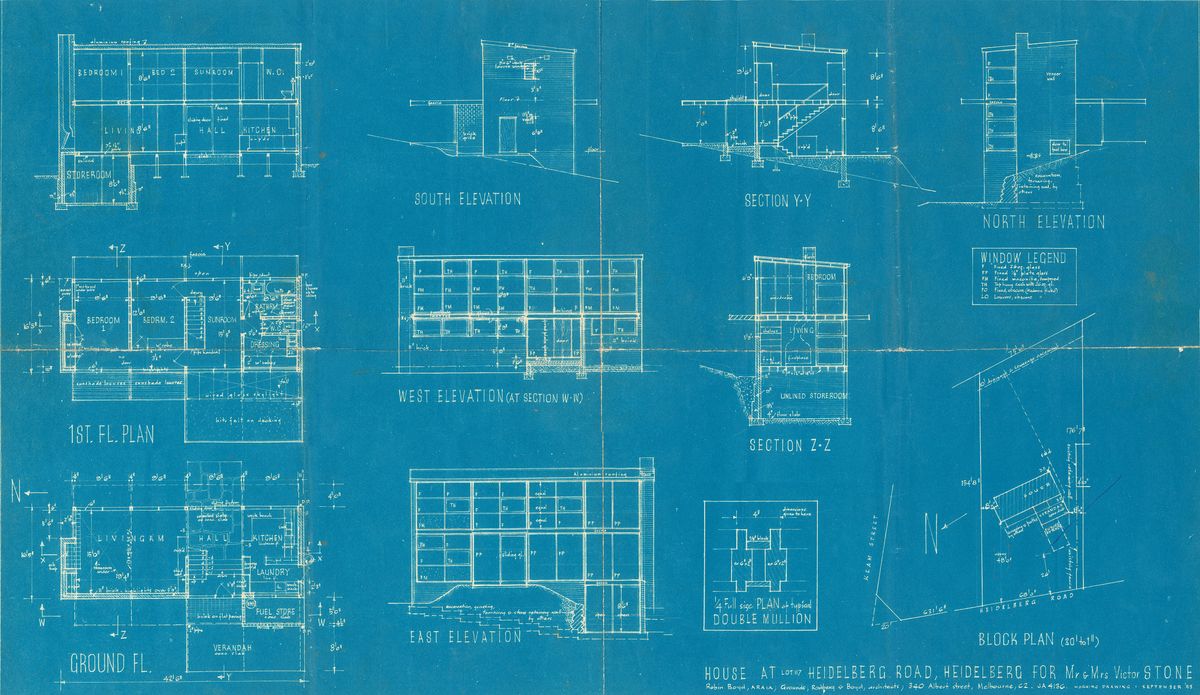

The original brief was very simple: a modest dwelling for a couple that intended to have children, with light, greenery and open space. The budget only allowed for kitchen built-ins, and the rest of the joinery would be purchased at a later stage. Boyd’s original design for the Stone House was terraced and linear in plan. It was divided into a large, open living and sleeping unit delineated by split levels rather than by walls, a much narrower service unit comprising kitchen and bathroom, and a slightly wider entry courtyard connecting the two units. Despite its modesty, the original parti is comparable to Boyd’s own house at Walsh Street (1958) in terms of its courtyard configuration, and even to the more radical Featherston House (1967), in which the courtyard becomes the living and sleeping area, rather than the intermission.

Martin Stone, Victor and Peggy’s son, tells me that the deal-breaker in this initial design was the lack of privacy for the bedroom. So Boyd reconfigured the plan and the new iteration – as Tony Lee, executive director of the Robin Boyd Foundation, has pointed out – maintained the parti but reduced the footprint by slicing the plan longitudinally, stacking the bedrooms on top of the living room and the bathroom above the kitchen. The courtyard became a glazed dining area at ground level and a sunroom (and study for Victor) on the second level. Boyd also took this opportunity to flip the plan so that the living area and main bedroom had a north-east orientation, presumably to maximize sunlight.

The design reflected the progressive attitudes of its owners: it debunked traditional notions of generational and gender segregation. Martin recalls, “People would arrive for parties, and they would be in the kitchen … at the table, and we [the children] were in the living room or perched on the stairs watching the goings on. There was no separation, you were always part of it.” In the early years, neighbours considered the house to be “an oddity.” The only other local example of the new Zeitgeist was Snelleman House (1954) on nearby Keam Street, designed by architect Peter McIntyre.

When a second child was born, the owners enclosed the carport to become a sunroom, with a new bedroom above.

Image: Sonia Mangiapane

Soon after the arrival of Helena, Martin’s younger sister, it was clear that the family was outgrowing the home’s original two-bedroom arrangement. “We were lucky that when we needed to extend, Robin was still around,” Peggy told me. “We decided to enclose the carport to become a sunroom and build a big room on top.”

Walking down the driveway towards the house, the extension is the first thing you encounter, but the join is imperceptible to the untrained eye. A closer reading of the floor plans reveals that Boyd approached the task pragmatically, and for obvious reasons. “We couldn’t go out either side, and didn’t want to go out [over the backyard],” Peggy explained. By that stage the garden had been planned by the famous landscape architect Ellis Stones. If Boyd had aligned the “window wall” on the new western elevation with the original structural wall dividing the dining and the services area, the concept of the open interstice would have been preserved. However, on a practical level, this would mean that the new bedroom would be exposed to the harsh western sun, and in any case, the separation of served and service areas was not relevant in this new configuration.

Over time, the garden has matured spectacularly: deciduous creepers shade the wall of glass at ground level during the summer, and drop their leaves in wintertime to let the sun pour in. Upstairs, cypress trees afford privacy, obscuring the immediate suburban development while framing views out over the hills. But aside from the landscape, the extra bedroom and some minor alterations to the joinery over the years, it’s remarkable how little the house has changed, considering the various permutations of family life. It has remained in the family for more than sixty years and happily accommodated a childless couple, then a young family of three, four and back to two again when the house became an empty nest and the “new bedroom” upstairs became a library. After Victor passed away, Peggy remained in the house, living independently until Martin returned home to care for her when she became less mobile. Sadly, Peggy passed away in 2012. Since then, Martin has retired and continues to reside in the family home.

Cypress trees, black bamboo and other foliage afford privacy, obscuring the immediate suburban development.

Image: Sonia Mangiapane

While the design for the house did to some extent anticipate the growth of the household, it was not designed to be inherently flexible, nor did it anticipate shrinkage. But rather than sell or rebuild, the Stones have continually repurposed their family home, which is a testament to its enduring qualities and their architect’s ability to interpret their lifestyle. In Martin’s words, “Boyd wanted to design houses that people could live happily in, which is why so many of us have remained in them since they were built.”

Robin Boyd CBE (1919-1971) was a renowned Victorian architect, author, critic and public educator in the 1950s and 1960s, a leader in Melbourne’s modern architecture movement, a visionary in urban design and outspoken on the “Australian identity.” The Robin Boyd Foundation continues the work and spirit of Robin Boyd through an active, innovative and ongoing series of public learning programs developed to increase individual and community awareness, understanding and participation in design.

i. Judith O’Callaghan and Charles Pickett, Designer Suburbs: Architects and Affordable Homes in Australia (Sydney: NewSouth Books, 2012), 40.

ii. Judith O’Callaghan and Charles Pickett, Designer Suburbs, 43.

Source

Project

Published online: 16 Mar 2016

Words:

Jacqui Alexander

Images:

Courtesy of the Robin Boyd Foundation,

Sonia Mangiapane

Issue

Houses, December 2015