<b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> Hamilton Lund

Portrait of Romaldo Giurgola by Mandy Martin. Martin describes the portrait as “presenting Aldo Giurgola’s life-work in the context of his life-journey. I wanted to present him as a man of humility who has truly served humanity and to represent this through his three ‘houses’, that of God, Parliament and his own house.” The painting is in three panels “united by the ellipse of light”. The first panel depicts St Thomas Aquinas Church, Charnwood, Canberra (MGT, 1989/90). Beyond the church are the snow-covered peaks behind the Technical High School at the small Italian village of Maniago (Mitchell/Giurgola Architects, 1981). In the second panel the Italian Alps connect to the Brindabellas in the ACT. This panel also represents Parliament House (MGT, 1979–1988), with Giurgola in the foreground, reflected in the pool of the Members Hall. In the third panel, the Brindabellas connect with a vista of the far shore of Lake Bathurst, where Aldo built his country house (2004), which is shown in the foreground.

View along the length of the new cathedral, with stone altar and cathedra by Anne Ferguson, aureole by Robin Blau and pews by Kevin Perkins.

The new entry to St Patrick’s, through the nave of the old building. Entry gates are by Robin Blau and the stained glass windows designed by Klaus Zimmer and fabricated in Germany by Derix Glasstudio.

Looking along the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament. The baptismal font in the foreground is by Anne Ferguson and the screens by Robin Blau.

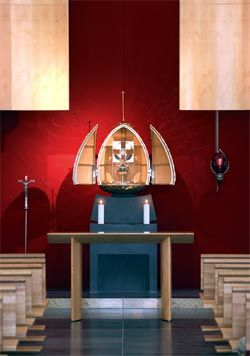

Altar furniture in the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament by Kevin Perkins and Tabernacle by Robin Blau.

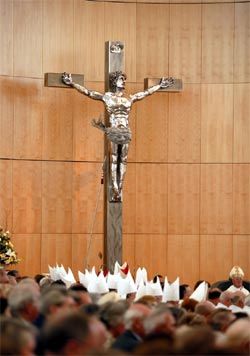

Cross with Corpus by Robin Blau, seen at the dedication of the cathedral.

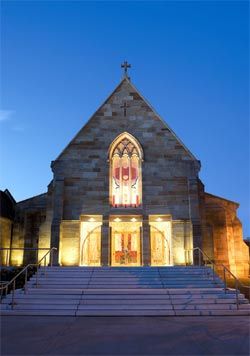

Entry to St Patrick’s photographed during the dedication.

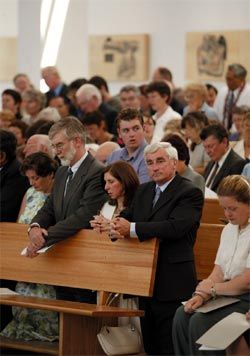

The first mass in the new St Patrick’s Cathedral.

The dedication, with Stations of the Cross by Philip Cooper seen beyond.

Justine Clark I’d like to begin with the portrait of Romaldo, which was gifted by the RAIA to the National Portrait Gallery at the end of last year. Can you tell me where the idea came from, and how the portrait was organized and commissioned.

Pamille Berg The idea began with David Thomas, the Chief Architect for the Joint House Department at Parliament House.

David noticed that there was no reference to the architect anywhere in the building, and he suggested that Parliament House should commission a portrait for the building. That got nowhere – politicians really don’t care.

This got him thinking about how architects are recognized in Australian society. Then he and several others, including RAIA ACT councillors, realized that the National Portrait Gallery only had three portraits of architects, none of which had been commissioned. This was disappointing given that the gallery’s brief is to represent people from all walks of life. So David, in association with the ACT Chapter, came up with the idea of the Institute commissioning a portrait to be presented to the gallery. This was agreed with the gallery in advance.

Romaldo Giurgola I was quite hesitant about accepting this. The idea of a portrait is not my cup of tea. But, after discussing it with Pam and thinking it through, I accepted the notion that it was really a celebration of architecture for the National Portrait Gallery. And the RAIA was the commissioner, the driver in a sense. So the process started and Pam was engaged by the RAIA to develop the design brief, which reflected the kinds of briefs she prepares all the time for artists. This began with a competition between three artists. Then Mandy Martin was selected on the basis of her sketch design. I had contact with her at three points in the process – in the beginning she asked for photographs and material, then in the middle with the initial sketch, then close to the end, when she already had already set up the portrait elements, we had another meeting with the committee. She made the final portrait from those discussions.

PB It was a very formal process, with a written brief. Each of the three artists was properly paid. There was a good solid commissioning committee with very different points of view. It had six members, some with qualifications in art as well as architecture, including the head of the National Portrait Gallery and the senior curator of Australian Art at the National Gallery of Australia. We also made Aldo a member, so that he was part of the process.

We always find it works well to create solid, professional, formal situations, which allow the artist to experiment within a protected environment.

At schematic design stage, each artist had five hours with Aldo to use any way they wanted – some people might want to come back and sketch over time, somebody might want to take him to lunch and drink a bottle of wine. The brief also included some of Aldo’s writings and we had a full-day design orientation with all artists going from building to building with Aldo talking about his architecture. This was the beginning of the inspirational process of exploring what a portrait in the twenty-first century might be.

This was an important question, as was the related issue of how do you make a portrait of an architect that conveys a commitment, a practice – particularly when it is to hang in the National Portrait Gallery.

The intention was to memorialize a practice and thereby memorialize an individual, as opposed to memorializing the individual and hoping that there is some resonance with the practice.

RG There was an interesting episode in the second stage. The basic idea of having the figure with the architecture in the background had already been approved, but I was concerned by the fact that I was pictured looking into the pool – I said, “that looks narcissistic”. But the committee was very good and pointed out that really I shouldn’t interfere. It was very true. If the artist has an intelligent brief, then you shouldn’t interfere because you can interrupt the flow of his or her thinking and the proper expression of things. That was a good lesson for me; I’m a little bit too emotional sometimes.

Once the artist has been involved in clarifying the process, they have to be left to develop their own ideas. In architecture, too, it’s so important to have everybody as part of the process on his own or her own terms. For example, with our work with Kevin Perkins on the choir stalls here at St Patrick’s, there was a certain moment when you don’t have to talk with him any longer, because he understands the process and the programme, and you shouldn’t disturb that.

PB Aldo is describing the process by which we collaborate with artists. It is not a “free-for-all, anything goes” kind of process.

Instead we try to give a clarity and a direction and then find those moments when it’s right to step back. With Kevin and the choir stalls, there were a whole series of very precise steps: going down to Tasmania and being in Kevin’s workshop; prototyping everything in MDF at one-to-one scale; sitting in it; asking, well if somebody is really fat can they fit, can they walk down the aisle, where’s the light, et cetera. But at the same time it was a matter of being able to see those things that Kevin could bring to it which, if we were too dominant, we would squash and kill. It’s a process that is forever intriguing and fascinating and very scary, because you never quite know how to do it. It is a nurturing process, both on their part and on ours.

The other thing about the portrait was that, although the artists selected were of national stature, we wanted artists who had never done a portrait before. So, to the extent that it was possible, everyone went through the process of thinking through the issues from the beginning. We find that really useful – to have very bright, good, strong people who are attacking something fresh. Remarkable things come out of that.

RG That was a great discovery for me here in Australia. Artistic output here is very spontaneous, it was a revelation to me.

I was used to New York, with all its galleries, where art was an institution. And in Europe the artist soon belongs to the academy, no matter what kind of attendance he has. But here there were all these people doing things spontaneously – they were living with it. There is a transformation of the whole perception of what an artwork or an artist is here. Imagine, people were in the middle of an abstraction in New York, and here you had people like Fred Williams and Arthur Boyd. I came here and everybody was working on the landscape. Nobody was working on landscape anywhere in the world. It’s wonderful.

JC Aldo, what aspects of your work did you want to be conveyed in the portrait?

RG Every project for me is starting from scratch. I really always think that the one that I have at the moment is the most important that I ever had, honestly. My approach has always been to discover all there was in a particular project and to work with that. I don’t have any prejudice about stylistic character or about my hand being present in the form of the building.

To be honest you don’t put a church into a situation of doing something that they can’t afford – and that is how things should be done all the time. Maybe it is because I am used to Modernism, but I feel it very profoundly. Otherwise, what is your responsibility to society? It’s not making a good firework; you have to be more than conscious of what you are doing.

PB In the portrait brief we described three important aspects of Aldo’s practice. Firstly, that he has done hundreds of public buildings and has been continually trying to figure out what it means to build responsibly in public. Secondly, that Aldo’s way of working has always been to roll up his sleeves – to sit down with the youngest members of the firm and his trusted associates and work again and again. We wanted to capture that sense of personal responsibility and involvement. Thirdly, that he has been interested in the notion of a humanist practice – how does one quietly entrench the resonance of content into a project. We included a quote from a paper by Harry Margalit, where Harry said that the work of Mitchell/Giurgola in the States and of MGT was firmly based in an understanding of Modernism which is framed by a sense of responsibility – of material, of cost, of modesty, of rightness for a situation.

JC So, Aldo, although you start afresh with every project, there are modes of working and general commitments to the idea of what architecture might do culturally which tie the work together.

RG Well, I have had many experiences, and I figured out that the important thing is the work and not the person. I’m also conscious of the fact that in this country it’s so very important to try not to be satisfied simply by a great exercise of talent. When Jørn Utzon came here he left a wonderful monument, but these things are very rare.

Also, the invention of the site that was given to him was the first great thing. I don’t know who decided that was the site for an opera house, but that was enough, because immediately it unleashed a number of attitudes and things, and certainly Jørn’s was the best one. But especially here, in this growing country, with this wealth all over the place, it’s so important to also approach things intellectually. You think about what you can do, and what you cannot do; about what is important for everybody else and what is just an exercise of the talent of a few people. It’s a consciousness which in architecture I think is essential.

PB Aldo also often says that his approach to architecture was conditioned by being caught in the war in Europe as a young man. It took a very important chunk out of his youth. Leading up to the war, Aldo and his friends in Italy placed great hope in existentialism as a way of avoiding what was about to happen. Then there was the cataclysm of the war. When Aldo was finally able to start practising architecture it was not about ephemeral stuff, it was not about a nice life. It was pretty seriously about finding ways to construct a good democratic society, and exploring what that means after something like the Second World War. Then Aldo went to the US, initially as a Fulbright scholar.

Aldo also came out of a time in Italy when an architect had a classical education.

Even in America, when Aldo was chairman at Columbia, students were encouraged to do a bachelor of arts where they studied literature and poetry and philosophy and history and everything else. Then they came to Columbia and did a two-year architecture degree. That was not thought to be a waste of four years; it was understood as a proper foundation for being an architect. In Australian architecture schools now there is a sense that 18-year-olds get trapped into an architecture programme where they never read Plato, they never read Faulkner, they probably haven’t read Tim Winton. They don’t have the opportunity to ask, “Who are the poets of this country?”, “What is my history?”, “Do I understand Indigenous culture here with all its disjunction?” et cetera. Such questions give an urgency to what architecture can be, as an art that synthesizes and acknowledges these things.

RG Look at the work we did with the artists here at St Patrick’s. We started from scratch.

They were artists that we knew, but they faced this problem for the first time. And they established a connection between the value of certain space, a certain light and so on and the object that they are making. It’s been a wonderful experience. For instance, with the Stations of the Cross, the artist connected immediately with the spaces we were designing. We started approximately at the same time, together, and the art belongs to the architecture immediately, to the point where we say we don’t put anything else here except the cross, because this so belongs. I have photographs without it and everything is an abstraction, whereas with the Stations it becomes something tangible, which starts to talk with you. This is really the secret of architecture, I think. It’s really important when the elements in it start to talk with you – a brick wall, a piece of stone, a piece of timber and so on. When you start to have this kind of response, because it has to do with the human being, not with an abstract entity.

JC You have said elsewhere that art should help and identify and extend the content of architecture, which otherwise tends towards abstraction. I thought that was an effective and quite beautiful way of putting it.

RG We succeeded because we started together. We all sat down in the beginning, before I even started making sketches of the building, and we talked about it.

PB We try to make each of these things slowly come to be, rather than looking for an instant solution. It takes a huge amount of time. St Patrick’s is seven years of our life, even for a tiny little $11.5 million building. We said to ourselves all along, “This is a very simple, very modest, very minimal place”. In one sense, it’s not a big deal, and yet for us and the participants and the Diocese, it is a big deal.

To me, having watched the architectural process over all of these years, the modesty of architects and architecture in the face of the task is such an important thing. When the modesty is there it has a chance of being right and when the modesty isn’t there, then it usually hits the rocks at some point.

RG Modesty is not submission. I admire the modesty of the arcade of the Ospedale degli Innocenti. That’s a modest piece of architecture, now look at that. The most beautiful buildings in Canberra are two little buildings, the Sydney and Melbourne Buildings. Everybody loves them, although they’ve been massacred in all sorts of ways.

The Capella de Pazzi in Florence is a modest piece, a very modest piece of architecture, but look at the resonance that Brunelleschi had in every direction.

PB Another part of Aldo’s work, which I got to participate in first hand and which also has something to do with the portrait and his practice, is the work he did with Pehr Gyllenhammar, who was then head of Volvo International. Pehr turned Volvo’s assembly line on its head. Instead of workers doing difficult things to make it easy to make cars, Volvo were the first to send car engines around on little robots, and to have design teams and work teams where people figured how they wanted to work and how they could build good cars. Aldo did a series of buildings, which culminated in the Volvo International Headquarters in Gothenburg.

He was also involved in masterplanning factory complexes and he advised on every significant building that Volvo built internationally through the Volvo Advisory Board on Architecture and Design. This was based on the premise that if everything that Volvo did – buildings or products or anything else – was excellent, then that would enhance Volvo’s viability. Pehr understood the value of good design, of good work and of good places. So, as an architect, Aldo could have important conversations with someone who understood the potency of the making. The role of an architect isn’t just about making buildings, it really has the potential, if it’s taken properly, to make a difference.

JC Can I ask a bit more about your role, Pam. How long have you and Aldo been working together?

PB We first met at the American Academy in Rome in the late 70s. We got on well and I started doing some writing and editing work for Aldo – I was an impoverished graduate student. Then Aldo offered me a full-time job in the Philadelphia office.

RG And Pam became partner in MGT in 1988, because embracing the critical ability that she had to offer was fundamental to us maintaining the direction of the firm.

PB It’s unusual to find an architectural firm that is comfortable having non-architects in it. Aldo and Mitch, his partner, found that it was a big asset to have someone who heard with ears that weren’t architectural ears, who thought with a mind that wasn’t an architectural mind. This helped the process of defining briefs, listening to clients, and trying to find the heart of the project. It was sheer privilege on my side.

It’s also important to acknowledge the way those offices worked, and the number of people who were close to Aldo, who had worked with him for decades, who really served the process of making architecture.

It’s very unbalanced to have this conversation without Hal Guida and the others. They were fundamental to Aldo being able to do what he did.

RG They were all students of mine in school, they came and worked for me and they are all there still here and in the office in New York.

PB The Philadelphia office has changed its name but it’s still there. And there is the legacy of FJMT in Sydney, of GMB in Canberra, of Mitchell/Giurgola in New York.

All those people have found their legs, and decided to go off and do architecture in a substantial way.

JC Earlier you mentioned in passing what it means to move to Australia, to emigrate.

Could you talk about this further?

RG There were quite a few Americans here when we were doing Parliament House – we had an office of 150 people. When the building was completed most left but some of us remained here – Hal Guida, myself, Pam. We started over.

PB And Rick Thorp, an Australian who’d been working in the New York office and was also an American citizen by then.

And as Aldo says, we started over. Even though MGT existed and it had employees, no one in Australia thought that a billion dollar Parliament House was a good recommendation for doing anything else.

So, although we had longevity and Hal Guida had already worked with Aldo for 22 years at that stage, we had to start a practice from scratch. It was very strange and wonderful but scary.

I still remember the first time that I flew into Australia, two years after the project had begun and we were ready to start the art programme. As we got closer and closer to Canberra I got more and more excited because there were still sheep and dams and trees and no city sprawl and I thought, “fantastic, this is a place that counts”. We thought to be able to live in a national capital and live in the country but still fly in and out easily to work on international projects was remarkable. I really didn’t want to go back to the US. The Vietnam War had been pivotal and I didn’t want to be a part of where America was going with its imperialism, even though my other American connections and roots, particularly with the west and the far north-west, were very strong.

To me, Australia was a place where you could live simply, you could live modestly.

I was hugely impressed with the socialism in Australia in the 1980s. It allowed professional people and other people a huge number of choices – you weren’t locked in immediately to the big mortgage and the 60-hour-a-week job. I married an Australian and have a remarkable life between the city and the country.

It was much more unusual for Aldo to decide to stay than for any of us because had he gone back to New York he would have plugged back into a world where he was known, he was esteemed, he had a position, he had a place, whereas in Australia, particularly in the 80s, nobody much cared who he was. It was a very courageous choice because he was nearly 70. But, in effect he said, no, I don’t want to just go back into the comfort of that architectural fraternity. I want to stay here and figure out what it means to build in a place I don’t know.

RG You always carry yourself with you.

I’ve found myself at home in many places; maybe it’s in my nature that I make friends anywhere through my work. But I really enjoy it here, I must say, without any pretence of just being nice because I am here. I really look at Australia as a sort of an ultimate place where things can happen.

It is the Antipodes.

JC Aldo, can you talk about Canberra and your ongoing involvement with the ACT.

RG Well, I knew about Canberra since I was at school in Rome. I remember Ludovico Quaroni showed us Walter Burley Griffin’s plan. I always admired the notion of building a place in relation to the natural environment. I have always considered that a building is not an ending, it is always connected, in both conceptual and physical terms, with the environment. So I aspired to see this place. In fact I thought it was already built, but instead there was nothing here at that time, only a hill.

Later I entered a competition for a memorial for Walter Burley Griffin on Mount Ainslie. Nothing came of it, but I was in contact somehow. Then John Overall came in our office to look for an assessor for the Parliament House competition. As soon as he started talking I said, “Look, don’t go too far, I would like to participate in the competition.

JC And you came and did Parliament House.

RG Yes, and I have always maintained contact with the NCDC, which became the National Capital Authority. I consult and recently I participated in the Griffin Legacy programme. I continue to be interested in the future of this city. In Canberra, there is always the dilemma of how far we should go before we say stop. I’ve seen many cities in the world, and beyond 600,000 people a city loses control of its independence.

So, I developed the idea that we can sustain the spirit on which this city was invented – not only by Burley Griffin because you know the problem that we have with the legacy of Burley Griffin; it’s nice and dandy, but there is always the danger of ending up with a physical reproduction of what Burley Griffin had in mind. That isn’t possible now – you can’t think any longer on those terms. But if you look too much at the geometry of that plan you are bound to do it. Instead you have to consider the initiative they had at that time – the spirit of making a new town, from the surveyor to the politician, from which they invented the idea of making a lake, and the emphasis on conservation, because that came very early.

I’ve been presenting the idea that, yes, you can establish a sense of a magnet city like Canberra, providing you are involved in a regional plan that makes sense. You can think in terms of the local region – in fact the more global you are the smaller you are – and take this territory between Goulburn, Canberra and Wagga, which has pretty much consistent physical characteristics, and limit the magnet cities and then try to develop the towns that already exist, so that there is always an equilibrium. The modern urban problem is that we always think of what happens within, rather than thinking about what happens in between. That is the really important thing to do.

The city could grow, but grow in a different way. Canberra can remain a hub and Wagga can be one and Goulburn could be one too, because it has other potential.

The point is to introduce the notion that those places already have their own culture, and you have to work with that, not try to transform everything all of a sudden.

PB It’s part of that spirit of generating ideas for ongoing discussions and bringing those ideas out of 60 years of experience of work to try and see where they go. That’s what he’s still doing. ROMALDO GIURGOLA NOW OPERATES A SMALL OFFICE IN CANBERRA WORKING AS A CONSULTANT FOR INDIVIDUAL CLIENTS. PAMILLE BERG AO HON. FRAIA, A FORMER DIRECTOR OF MGT ARCHITECTS, IS THE DIRECTOR OF PAMILLE BERG CONSULTING IN CANBERRA, PROVIDING PUBLIC ART MASTERPLANNING AND COORDINATION SERVICES TO ARCHITECTURAL FIRMS AND PUBLIC CLIENTS.

RAIA Giurgola Project committee Ross Feller, Catherine Townsend, David Thomas, architects; Dr Eugenie Keefer Bell, designer/maker and lecturer; Dr Andrew Sayers, Director of the National Portrait Gallery; Dr Deborah Hart, Senior Curator of Australian Art, National Gallery of Australia.