As a creative endeavour, a garden could be considered a work of art. Roogulli, a bold, contemporary ten-hectare residential garden near Canberra, is a project that may well achieve such a classification as it matures. The field of art, however, is highly contested in Australian culture, where an implicit hierarchy pervades and two-dimensional visual art is the starting point. Other creative arts such as poetry, music, the performing arts and architecture jostle for recognition and gardens are rarely mentioned in this context, except perhaps as settings for sculpture or theatre.

This is despite a long international history of extraordinary gardens that are widely recognized as art and manifest aesthetic sensibility, symbolism and meaning. These gardens speak not only of their creation, but also of their time, place and culture. They continue to be revered, cared for and discussed, and influence other art forms such as painting, writing and film.

If the virtues of historic gardens can be so appreciated, why is it that our contemporary gardens are not?

Located in Bywong, ten minutes outside of Canberra on the tablelands of southern Australia, Roogulli was jointly created by landscape architect Jennie Curtis and permaculture designer and chef Chris Curtis, both of Fresh Landscape Design. From the degraded site they acquired in 1996, which was part of a larger grazing property that had been cleared of trees and seeded with introduced grasses, their objective was to create a place where they could live simply and sustainably and, as Jennie noted, “have a garden that looks good.”

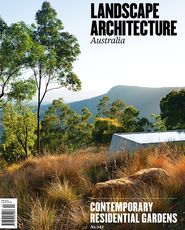

The house as seen through a shelter belt planting at the perimeter of the property.

Image: Dianna Snape

The strategies used to create Roogulli over the past fifteen years or so have hinged on two key ideas. The first relates to an aesthetic of ecological design, where the visual attributes of the garden reflect its purpose, location and climate. The second idea is the ethics of sustainability, where the garden demonstrates the principles and practice of sustainable design.

The site’s advantages include its approach from the south, which provides views over north-facing slopes onto distant vegetated hills, and access to a creek; the major challenge is the climate. The Curtises needed to come to terms with freezing winters, hot and dry summers, severe winds and low and variable rainfall. A decade-long drought emphasized the relentlessness of nature, the importance of working with natural systems and that if sustainable design was to be achieved, this would have to be a garden that would develop slowly.

As a deeper understanding of the capabilities of the site developed, a concept for the garden evolved. Conservation work started well in advance of any building work. Shelter belts were planted along boundary fence lines, erosion was stabilized, a large naturalistic dam with an island was formed and native grasses were progressively introduced to replace the non-native and noxious species. Construction of the house and garden started in 2004 with an integrated plan for the house, infrastructure and surrounding garden spaces.

The house is set into the slope towards the top of the site, where it is sheltered from westerly winds and has maximum access to views and northern sunlight. Courtyard spaces provide intimacy, shelter and shade while intensive and extensive food growing areas, some with irrigation, are set either side of the house to enable easy access. A food forest, grazing areas and cropping and regeneration areas, some with moveable fences, were established in an interconnected and logical manner further from the house.

The kitchen garden is draped in netting.

Image: Dianna Snape

In keeping with principles of sustainable design, alpacas, llamas, sheep and pastured poultry help manage the grassland and recycle nutrients for the vegetable gardens. Earth excavated during the construction of the house was turned into mudbricks and recovered pieces of shale were used to line drainage swales and mulch garden beds. As an aesthetic statement the colours of this earth and stone have become part of the colour palette of the garden. Slowly, with the use of local native plants, low-impact techniques and salvaged materials, the garden has been coaxed carefully from its degraded condition to become a celebration of light and sky, distinctive of this place and of living sustainably.

Roogulli is not easy to classify by style. It is not a hortus conclusus (enclosed garden), although it has courtyard spaces and contained garden areas. It is not a horticultural garden overflowing with plants, although it offers a rich diversity of plants with its native grasslands and seasonal abundance of flowers, fruit and vegetables. It is not a picturesque garden, although the experience of moving through the spaces is one of light, shadow, colour, texture and unfolding views. It is not a garden to take in at one glance, nor is it a garden that is complete, but there is an overall feeling of unity and stewardship.

Ideas that inspired Roogulli’s creation relate to landscape design and permaculture theories, and an understanding of ecology and of sustainable design as a process. But these do not translate easily to a visual language. Other ideas derive from visual representations of nature by Australian artists as well as the symbolic language of nature. Landscape painters such as Arthur Boyd, with his iconic renderings of the nearby Shoalhaven region, have reignited an appreciation of the aesthetics of rougher, dryer natural landscapes.

So, can this garden yet be considered a work of art? If a work of art is a creative endeavour driven by a key idea or theory that engages with the mind, then Roogulli is such a place. It presents a view of idealized nature in this degraded part of the continent and provides experience of that ideal at all times of the day and across all seasons. Neither static nor complete, it is an orchestrated collaboration with nature and a vision of sustainability that engages the intellect and the senses. It can, therefore, be classified as an intensely site-specific work of art.

Credits

- Project

- Roogulli

- Practice

- Fresh Landscape Design

NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Jennie Curtis

- Consultants

-

Architect

Peter Adamson Architects

Landscape contractor Out & About Landscapes

Permaculture designer Chris Curtis

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 180 months

Construction 180 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Outdoor / gardens

Source

Project

Published online: 8 Sep 2014

Words:

Dianne Firth

Images:

Dianna Snape

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2014