Regional Associates – founded by Ross Langdon, Campbell Drake and Ben Milbourne – is investigating architecture that re-engages with local sourcing of materials, upcycling and on-site fabrication, as well as developing the ingenuity and skills found within the community. While Regional Associates quite consciously associates itself with a renewed call for regionalism, there is more to its approach than resistance to the universalizing forms and aesthetics of modern industrial construction.

Regional Associates (L–R): Campbell Drake, Ross Langdon and Ben Milbourne.

The dialogue with the local begun in this first series of projects in East Africa arises as much from economic and infrastructure constraints, as well as the demands of environmentally sensitive sites, as it does from the intent of the designers. This approach is also reminiscent of a growing international voice in architecture, best known in such diverse practices as Studio Mumbai, StudioMAS, Peter Rich Architects and Estudio Teddy Cruz, who declare themselves part of an era in which the problem of “how to become modern and to return to sources” has become more compelling. (Kenneth Frampton referencing Paul Ricoeur in “Towards a Critical Regionalism: six points for an architecture of resistance,” The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, edited by Hal Foster, Bay Press, Port Townsend, 1983.)

Kyambura Game Lodge (adjacent to Kyambura Gorge, Kyambura, Uganda), Buvi Lodge (Entebbe, Uganda) and Alphonse Island (Seychelles) are among the practice’s first projects, each providing tourist accommodation and access to a wildlife conservation reserve (for chimpanzees, birds and marine life respectively). Such distinct and remote natural habitats have necessitated considered responses to site. Yet the familiar question of authentic architectural expression versus nostalgic romanticism has also arisen.

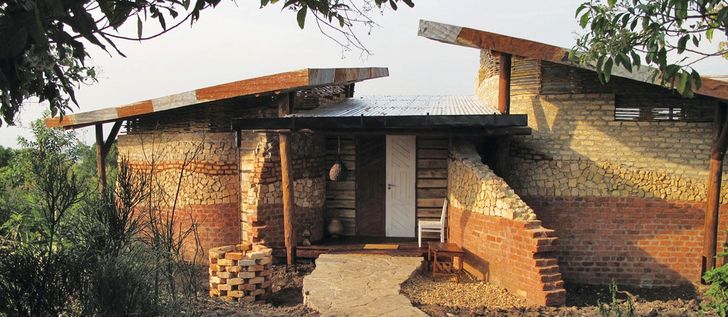

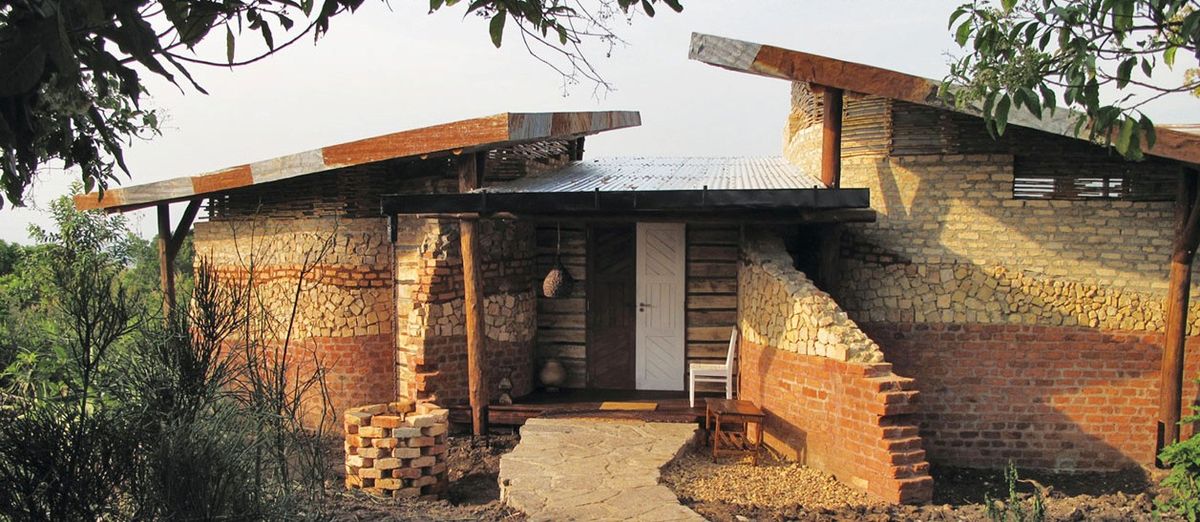

Entrance, Savannah Banda 2, Kyambura Game Lodge, Uganda.

Image: Ross Langdon

Over time Regional Associates has challenged its clients to move away from a desire to re-create traditional structures. Clearly visible in the bandas of stage two of Kyambura Lodge, for instance, are the sediment-like layers of different kinds of brick, stone and mortar that respond to surrounding settlements. Local houses are often constructed in bursts over time as funds and materials become available, the layering simply a consequence of building with what is at hand. While the projects borrow heavily from the local vernacular, influence is also taken from more contemporary local practices: both material (such as the local recycling) and cultural (such as related artisanal skills).

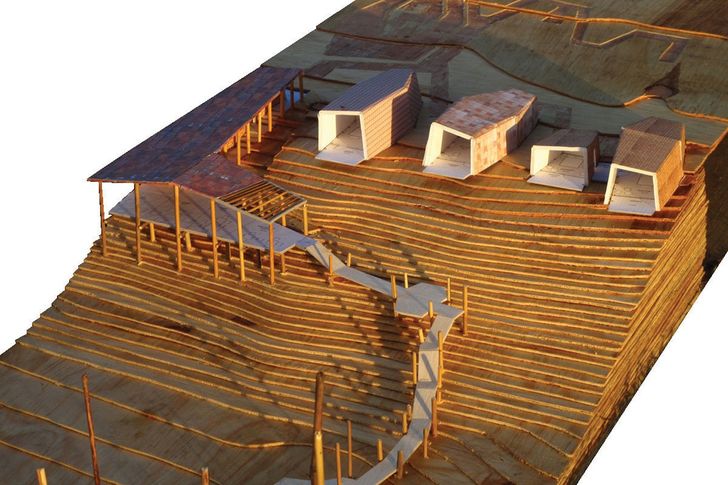

Schematic models of the Buvi Lodge, Lake Victoria, Uganda.

Working in contexts where materials are expensive and labour cheap has also meant inverting many of the typical approaches to building. For Buvi Lodge, construction of which began in 2013, the tidiness of handing responsibility to a single contractor or packaging trades is nonexistent. Instead the materials are sourced and collected on-site by the client prior to engaging labour. At Kyambura Lodge, similar circumstances allowed for experimentation with local artisans, on everything from the primary structure to bespoke furniture and lamps inspired by local products at the markets.

The construction site of Buvi Lodge, Entebbe, Uganda.

Image: Ross Langdon

Unlike the throwaway culture of Western countries, in Uganda salvaged materials can be difficult to come across. “In Africa [waste] doesn’t exist; everything gets reused,” says Drake. The materials for the banda roofs of stage two, which trace the landscape form of the surrounding hills, were sourced through collaboration with an NGO that provided new roofs to a number of local houses. Their old rusted roofs were then harvested for use in creating the patchwork second skin of the bandas and strips of metal woven into lampshades. The Buvi Lodge promises to explore these approaches further, tempering even more contemporary formal gestures with the same local materials and techniques.

Schematic model of Alphonse Island, Seychelles.

Ross Langdon and Campbell Drake met in London, where Drake was studying for a Master in Research Architecture at Goldsmiths. Ben Milbourne had previously worked with Drake in Indonesia and knew Langdon from studies in Tasmania and then Sydney. Bolstered by Langdon’s and Drake’s separate commissions in East Africa and by their obvious overlap in interests, the three formed Regional Associates. Having the flexibility to collaborate over distance (the directors often work from different locations) was an early determinant of Regional Associates’ business model. This collaborative structure also provides Regional Associates with a robust internal dialogue.

“We have interesting debates about how we approach each project. We might really want to push different avenues of research or site response or project approach, and that’s what creates such variety in the way that we work. We want to be flexible and open and that’s what the business model’s all about. It’s a dynamic thing within the practice,” says Langdon.

Regional Associates continues to broaden this structure, most recently recruiting local partners. This allows the practice to expand and shrink teams as required by geographically diverse projects, but also to spread its working ethos and knowledge. Like Peter Rich, Regional Associates is aware of the potential for each project to build marketable skills among local professionals and industries and/or for the built results to resonate through emulation by other developers in the region. The practice has also found clients to collaborate with who directly invest in community development and who intend to train and employ local staff once in operation. Such awareness goes some way towards negotiating the obvious cultural quandaries and economic inequalities that surround engagement of foreign architects in developing countries.

An interesting thread throughout these projects is the figure of an architect who is once again involved in all aspects of procurement and construction. In Australia such an approach is easily pushed aside: industrial building materials are simply too readily available and cheap, and labour too expensive. Yet, as can be seen in other industries, there is also a burgeoning desire in developed cities to recycle and upcycle materials, to use locally produced building products and to revisit artisanal making. It raises the question of what broader role might become possible for the Australian architect by purposefully relinquishing control of a singular vision and engaging in design through a more slippery negotiation of material, cultural and economic contingencies.

Source

People

Published online: 23 Aug 2013

Words:

Anna Tweeddale

Images:

Llatzer Planas,

Ross Langdon,

Tanja Milbourne

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2013