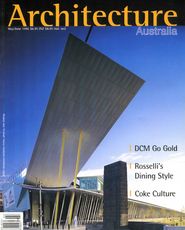

The Coke bottle shop selling Coca-Cola merchandise in the ground floor foyer.

The new Coca-Cola Quayside is the first Australian museum devoted to the products of a single manufacturer. There have been historical displays of products installed in the premises of various prominent companies, but none have been in a prime location and none have come with an entry fee. But the Coke museum, sitting overtly in the front stalls of Sydney’s new arts circuit around Sydney Cove, aims at both cultural and curatorial seriousness and the commercial high ground. What then are we to make of a cultural institution that devotes itself to the history and sale of a sugary drink in a cute bottle?

Coke is not really about anything functional like quenching thirst. Like cigarettes and cars, it cloaks itself in a magic of youth and desirability, of inevitability: this is an important example of the manipulation of simple products to carry greater power than their list of ingredients would suggest, to the greater profit of their owners. To treat soft drink as worthy in itself of a whole museum may be disregarded as a simple marketing ploy—a means of reinforcing the special qualities of one particular brand, linking it inseparably with the birth and development of the mid to late-20th century’s youth culture. To measure the power of Coca-Cola, a product of doubtful real physical utility, it is valuable to imagine a similar museum devoted to a useful but unglamorous product like Ajax or Sorbent—how would it fare in the serious cultural stakes? Or in the commercial market?

Looking from the mezzanine to the ground floor lobby; the curved red wall conceals the sampling room; the lift is enclosed in a glass shaft. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

With interesting, ‘worthy’ and equally snappily-designed public museums like Sydney’s wonderful Earth Exchange (aka The Geological and Mining Museum) closing for lack of commercial patronage (or corporate sponsorship?), the Coke museum, at $5 a pop, can scarcely be regarded as a simple money-maker. Nor can it be a piece of altruism, a contribution to the rich cultural life of the nation. No, the Fountain of Drinks in the back, the Make-Your-Own Coke Advertisement booth and the groovy shop at the very front door tell the message—this is all about marketing the “Real Thing”.

That the fitout of the museum was directed by one of Sydney’s eminent good-taste architects, the creator of many mainstream art galleries, Andrew Andersons, reinforces its would-be serious stance and a testament to the power of the product. With co-director Bruce Eeles and project architect Jon Cullen, Peddle Thorp & Walker have created a suitably entertaining interior, with a strong presence and some elements of real technological adventure. Over two levels at the base of a small sixties office building belonging to Coke’s local bottlers, Amatil (who also bring us a variety of cigarette brands and grog), the museum comprises an entry space with counter and cash registers, a shop and a central atrium, behind which is the drink fountain. A glass lift and a glass block staircase lead up to the main galleries, a ring of spaces around the void which is focused on a video wall.

Coke’s history on display on the mezzanine level. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

The fitout takes the glass Coke bottle as its starting point, most literally in the shop, which is cut from fabulous great thick slices of greenish glass magically supporting the merchandise, allowing us the experience of walking inside the bottle itself. This was intended to form the exterior wall of the museum at street level, but an inexplicably nervous city council vetoed this piece of overt architecturalisation. The lift is a different icon—cubist and refined, its Foster-like detail deliberately mocked by its intense yellow glass. Other glass elements are less pure and less adventurous. Curving and straight walls of internally coloured glass blocks, owing a debt to Chareau, define the atrium space, while backing the drink fountain is a wall of fluted white glass with bubbled water falling behind it, like a captive eternal spring of lemonade.

The overall spatial layout is simple and rectangular, offset by the 3D sculpture of the Coke bottle shop and some subtle curves on both levels. There is no mystery or sense of enlargement to the space—what you see is what you get, and this suits the family with kids who, together with US-obsessed tourists, must be the target audience.

Stainless steel display cases are suspended from the glass fins of the bottle-shaped shop. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

The museum’s content is equally straightforward and presents an almost fetishistic, single-minded focus on the product. Its manufacturing and marketing history fills a sequence of handsome ash-veneered showcases, whilst aurally and visually dominating the centre of the museum is the video wall—showing, to the irritating accompaniment of an animated narrator who ensures that our attention span is limited to 30 seconds, the history of Coke and its advertisements against a backdrop of 20th century events—war, sport and pop music predominate. A 1950s bottling machine is unfortunately inoperative—a missed chance at a real experience, whilst the Make-Your- Own Coke Ad booth provides some hands-on entertainment. The whole is full of the same sort of happy, well-groomed, uniform(ed) hostesses that people McDonalds ads— with the same message of wholesome conformity.

A nice little museum, with a quality fitout showing spirit and adventure, but a worrying precedent for our cultural soul.

Credits

- Project

- Coca-Cola Museum, Sydney

- Architect

-

Peddle Thorp & Walker

- Project Team

- Andrew Andersons, Bruce Eeles, Jon Cullen, Jacqueline C Urford, Terry Brabazon, Nick Bucciarelli

- Consultants

-

Builder

Buildcorp (architectural), Lamond Building (exhibition)

Exhibition designer Nova Communications

Hydraulic and fire services engineer Smith Paul & Partners

Lighting and electrical engineers Barry Webb & Associates

Mechanical engineer Steensen Varming

Project manager P&J Projects

Quantity surveyor Rider Hunt

Structural engineer Taylor Thomson Whitting (TTW)

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built