Designed between 1988 and 1993, this house in Mount Wilson was commissioned by Geelum and Sheila Simpson-Lee, a retired dean of economics and a potter, who asked for a “secular monastic” house and studio with a “minimal tough simplicity.”1 They required an extremely light building. This was sometimes in the sense of a visual and physical lightness; at other times, it was unpretentiousness. Architecturally knowledgeable, their decision to work with Glenn Murcutt was deliberate. In their ethics and aesthetics they felt aligned with the minimal impact of his approach.

Located in the Blue Mountains, a World-Heritage-listed landscape to Sydney’s west, the site is in bushland on the edge of a national reserve. All projects here are subject to conservative regulatory prescriptions regarding appearance, heritage concerns and bushfire management. Murcutt has noted the difficulty of working in this context, his architectural preferences not easily accommodated. Terse argument and detailed adjustment gradually allowed the design to comply with governmental regulations. Reflecting on the arduous process, he commented, “It finally took twenty-one months to clear the planning and building authorities.”2

Client involvement at every stage of the design process led to vigorous debate and hard-won decisions. Murcutt specifically recounts a spirited critique of even the engineering drawings. The specified standard steel members were questioned, and a reduced size for each section was strenuously encouraged. Preferring a more expensive customized beam, Geelum argued, “What this country needs is more labour and less material.” His conception of economic advantage valued a broader social ethic over cost savings.

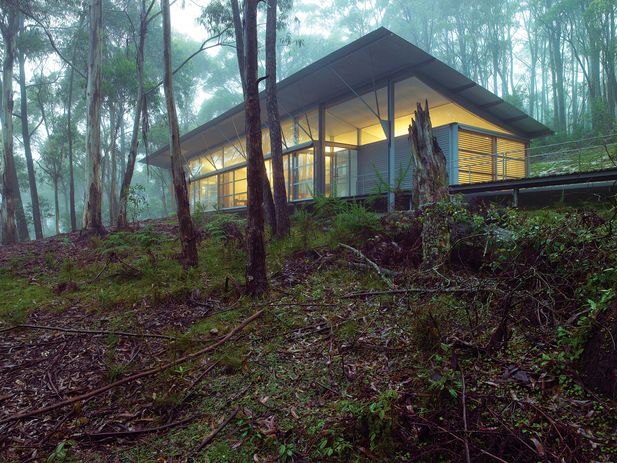

The pavilion outlook is orientated across a fall in the landscape.

Image: Richard Powers

Alignments and tensions between client and architect, between shared environmental ambitions and local governmental conservatism, intensified Murcutt’s inherently disciplined method. The architecture developed is newly austere and abstract, this quality extending from the overall building and its situation to all material details.

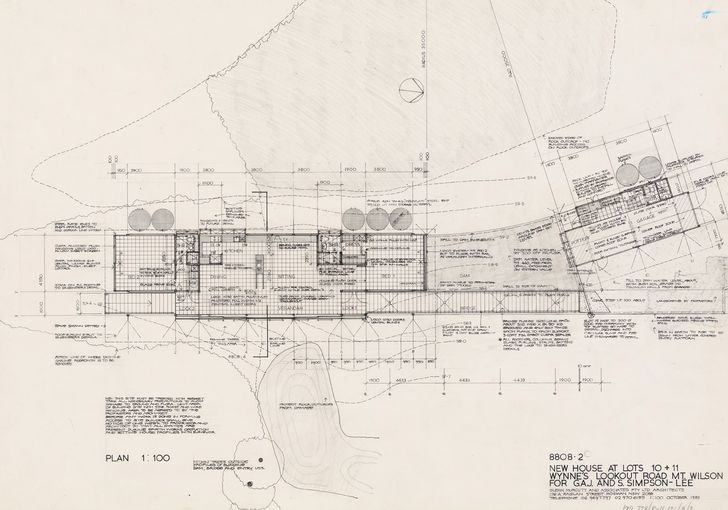

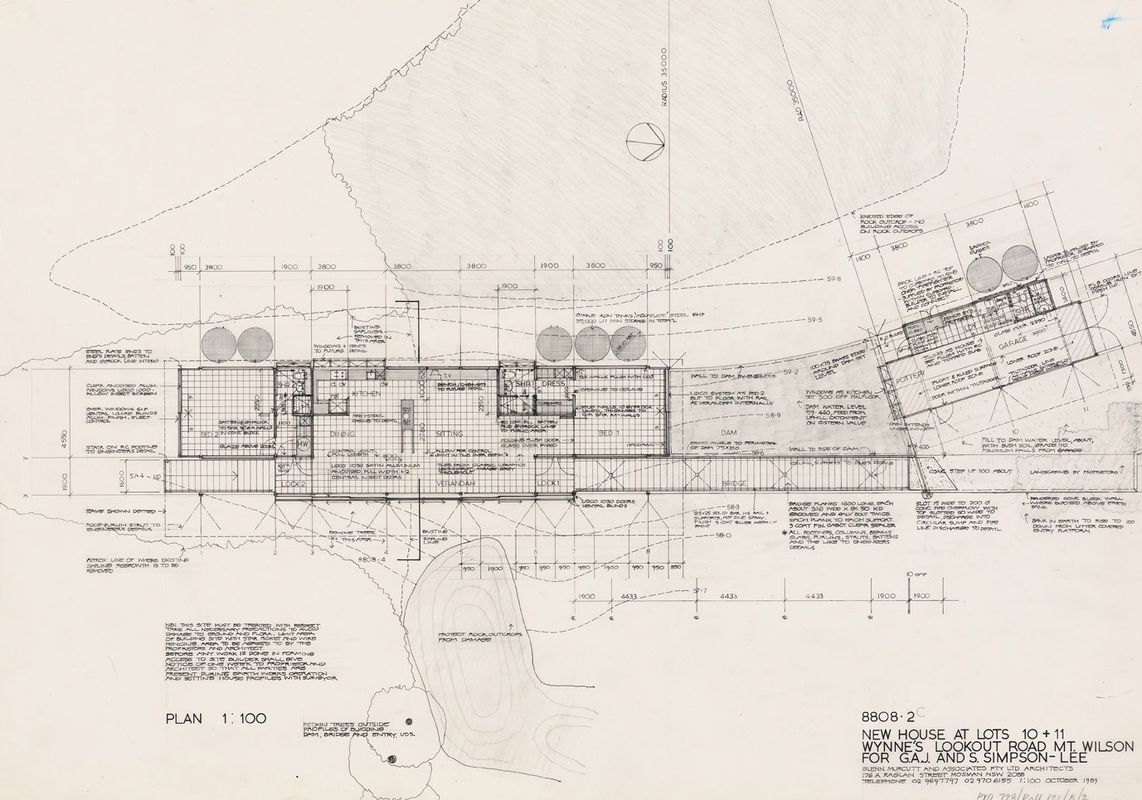

In early sketches the project follows a familiar initial strategy: a north-facing pavilion organized as bays, larger rooms on the northern glazed side with service facilities to a principally closed rear. Angled roofing protects the building in summer, allowing winter sun access. In the eventual siting, unexpectedly, this house plan was rotated ninety degrees to align with an existing bush track, the latter incorporated as the building’s circulation. This kind of reorientation is unusual for Murcutt as the mechanisms of climatic control implied by his directional section are wedded to a northern aspect for their success. The new placement, however, offered a significant economy in allowing a single-storey building to be more easily constructed along the flatter site contours with minimal adjustment to the existing ground. It further oriented the pavilion outlook across a fall in the landscape.

The final plan for the house. Drawing: Glenn Murcutt. State Library of NSW – PXD 728/Roll 121.

The final built linear path connects a garage/studio to a major living pavilion. A bridge, passing an external pond, includes this liquid platform within the built extent of the house. Entry is via a vestibule, one of two that bracket glazed openings to the living areas. These vestibules accommodate a series of sliding screens, allowing a glazed wall to completely disappear and the living room to be experienced as an open verandah. In this process of reorientation Murcutt’s apparent desire for universality, a generic solution to the house in a landscape, initially described via the simple logic of a north-facing pavilion and its component parts, is ultimately re-imagined as a heightened experience, an immediate connection to nature suggested by the minimal shelter of a refined path and camp site.

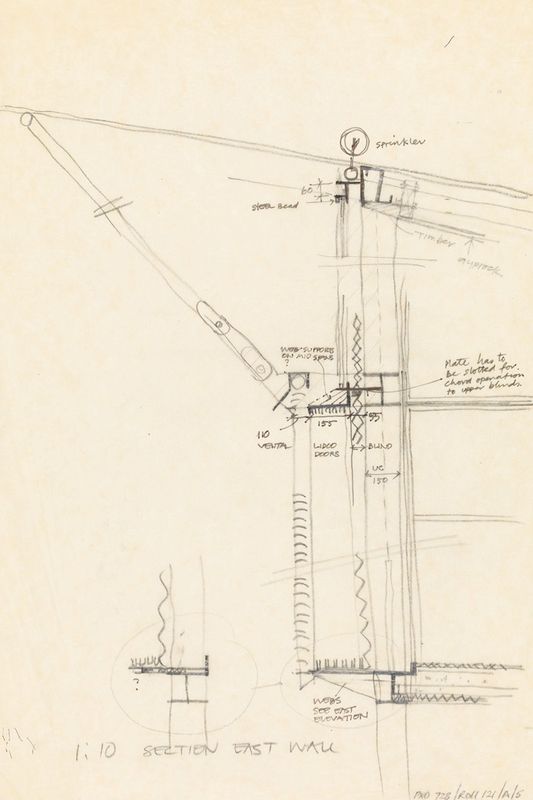

With the location and principal components established, this project developed over several years and via continuous and subtle adjustment was gradually refined. Its evolution is particularly visible in a series of section drawings at 1:20. These dry, economical drawings operate as both a mode of thinking and a medium for construction, and Murcutt’s architecture seems to substantively appear through numerous reworkings of this section.

An intricate knowledge of many off-the-shelf materials and prefabricated building systems informs these working drawings. The documents are heavily notated and specifications form an integral layer. Studies of Lidco standard aluminium sliding door and window glazing systems are indicative. Murcutt began using Lidco in the 1960s and has since employed this building component in successive projects. In spite of his clear familiarity with the product, in each project aluminium details are redrawn in plan and section at half and full scale to rethink and newly contextualize each element. The Simpson-Lee House drawings exemplify this process. Studies show stripped glazing extrusions coupled with rotated identical supports. Murcutt removes the handle on the sliding door and inverts the section to double as a handle. The interlocking of the elements improves structural stability and allows two vertical elements to read as a single glazing jamb. The overlapping provides a weather seal and reduces the total width of the accumulated layers. Standard sections are in this way continually reconceived to use less material and yet perform more functions. This design process is alluded to by Murcutt: “I always felt if you found a solution which did three things rather than one that the solution was getting somewhere.” Economy of means is implied as an ambition on several levels. In the Lidco example, the resultant elements are finer, thinner, visually lighter and simpler in appearance, yet they satisfy several levels of desired operation.

A “refined path and camp site,” the house offers an immediate connection to nature.

Image: Richard Powers

This manner of thinking informs Murcutt’s general architectural development. Early thoughts on the integrated structural roof system at Simpson-Lee, for example, can be seen in an earlier project at Bingie Point. There, Murcutt achieves an improbably thin roof for a house that feels unexpectedly light, almost transportable. In the later house this thought in construction is re-used and the material representation even further reduced. This roof extension is more abstract and singular. Here, the entire roof element can almost read as a single corrugated metal sheet. The resultant ethereal detail is particularly remarkable for incorporating sprinkler pipes, providing bushfire protection. Murcutt comments: “The result of all this hand-crafting is a lighter building and an economy of materials … the building has a seamless quality about it; it feels as though it is just hanging on by its fingertips. One of the builders who looked at it initially said it was impossible to build and that the roof would not stay up on that structural system. Of course, it was perfectly fine.”3

Interrelationships between the Bingie Point house and the Simpson-Lee project are emblematic of the architect’s working method, which operates at multiple levels. Environmental control strategies, individual materials and details, discovery and re-employment of functional elements, and even entire building types are continually re-used and tested in each new architectural situation. Material reduction and adaptation are here achieved through repeated adjustment; “ordinary” elements are continually reframed as refinements.

One finds a resultant tension in Murcutt’s work between two economies: system building, detail development and component re-use on the one hand, and a terse final abstract singularity on the other. The Simpson-Lee House is a development of the Bingie Point pavilion, yet more concentrated and refined, and the result is much more austere. It offers a new elemental whole. Three architectural components – a wall, a screen, a platform and roof – all appear to float apart. Emblematic of this separateness is the design of the central pond, an implied void. As a constructed space between two pavilions, it heightens one’s experience of the reflected sky and landscape, while at a bluntly functional level it collects water for survival and firefighting. As an architectural clearing, it anticipates the act of building in this forest and creates a precise yet ethereal platform, suggesting elemental inhabitation. In this particularly light house, apparently ordinary building elements are assembled to make possible a heightened minimalist experience.

On completion of the house, Murcutt was asked whether the Simpson-Lee project was personally significant. He was unequivocal: “Oh, there is no question of it. I can stand aside and simply say, ‘I am terrified that I will never do this again.’ It is that sort of feeling. I say that in a very humble way because I don’t know how it really happened. I know that when I calculate the hours that I worked then I can tell you how it happened; a lot of it was not easy and very complicated. My client scrutinized every detail … It is a building that through my clients, I developed to a level beyond which I have never achieved before.”4

In 1995, public recognition followed and the house received the prestigious Wilkinson Award for Residential Architecture from the Australian Institute of Architects (New South Wales Chapter). Since that time it has been widely appreciated as a critical moment in the development of Murcutt’s architecture. For many years the building’s unchanged austerity was enjoyed by its owners and in 2009, several years after Geelum passed away, Murcutt was offered the property by Sheila Simpson-Lee. In this deeply personal exchange, the custody of the home was deliberately passed to its architect.

1. Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper, Glenn Murcutt: A Singular Architectural Practice (Mulgrave, Victoria: The Images Publishing Group, 2002), 124.

2. Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper, Glenn Murcutt, 124.

3. Lucy Creagh and Richard Francis-Jones, “Mount Wilson House: 1994 Interview with Glenn Murcutt” in Jackie Cooper, Lucy Creagh, Richard Francis-Jones and Lawrence Nield (eds), Content (Sydney, FOG Publications: 1995), 76.

4. Lucy Creagh and Richard Francis-Jones, “Mount Wilson House,” 77.

Credits

- Project

- Simpson-Lee House

- Architect

- Glenn Murcutt

Australia

- Consultants

-

Engineer

James Taylor and Associates

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 10 Nov 2014

Words:

Maryam Gusheh,

Catherine Lassen

Images:

Richard Powers

Issue

Houses, August 2014