Cape Tribulation marks the point at which twentieth-century Australia ran out of gas. All the highways, byways and fast-food outlets that connect the ephemeral settlements further south converge at the Daintree River car ferry, where an ecotourist service road then winds another forty kilometres north through the virginal rainforest to Cape Tribulation. The bitumen then degenerates and collapses, lurching on only as an unsealed track – reserved for cassowaries and supply vehicles – to the unknowables of the Cape York Peninsula. Like Port Augusta on the edge of the Nullarbor Plain, Cape Tribulation is the end of civilization as we know it. And although it forms an exceedingly beautiful punctuation mark, the far north of Queensland is very hot, very wet and totally tropical and – with the honourable and isolated exception of Darwin – the rest of built Australia is not.

Tropical Australia requires tropical architecture, not Australian architecture. It might be observed that to conceive of anything other than truly tropical architecture north of Tully (Australia’s wettest town) would signify a wilful disdain for the relentlessness of the climate, and that to blithely adapt models used in temperate southern states – whack on a few sunshades, nail up some battens and let the airconditioning do the rest – would demonstrate sheer bloody-mindedness. Genuine – by which I mean sustainable – tropical architecture must provide passive ventilation and comprehensive shelter from the extremes of the sun and rain, and the architect must possess an almost fearful respect for the ravages of weather. Formal expression can only be successfully indulged by the elaborations of structural necessity – massive overhanging roofs, elevated ground planes and permeable facades – rather than by abstracted absorptions in referential game playing. Whisper it quietly, but when glimpsed from the southern compounds of contemporary artifice, tropical architecture must look curiously un-Australian. Up north, sustainability is not a preference but an imperative, and flamboyance is phenomenological rather than cerebral.

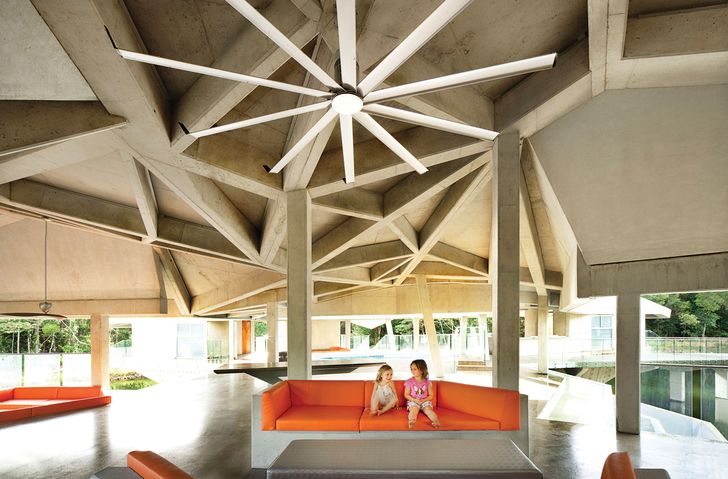

Located at Cape Tribulation, Stamp House is a concrete residence with six pods dramatically cantilevered over a lake.

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Charles Wright, director of Charles Wright Architects, has worked from Port Douglas for ten years and is thoroughly immersed in both the tropical geographies and the social peculiarities of Far North Queensland. The landscape is verdant and luscious, akin to those of Tahiti and the Seychelles: mountains meet the sea and the breezes are blissful, languid and seductive. But this paradise on earth has attracted a not entirely symbiotic collection of migrants from the south, be they overly moneyed retirees or escapees from suburban failure. The urban landscape and social networks of Cairns and Port Douglas are those of the southern cities gone troppo: they are unselfconsciously colourful and noisy, the good times prevail and previously constrained notions of taste have been recalibrated to suit. However, many of these new settlers have not become Queenslanders – rather, they have embraced a la la land that was there for the taking, as the Midwesterners once did in California. And as with his Californian architectural antecedents, Wright has delighted in the lifestyle, revelled in the landscape and the weather and treated every commission as an opportunity for innovation and expression.

Devoid of the cynicism that might identify a bona fide Queenslander, Wright has acknowledged and accepted the social milieu for what it is, has single-mindedly devoted himself to the principles and the practice of tropical architecture and, perhaps most intriguingly, has eschewed any discernible trace of Australiana in his conceptual designs. Socially, his work must be seen in the context of the imaginary lands of the past and present, and architectonically as part of a genre categorized by latitude rather than nationality.

The un-walled communal spaces of the house remain open to natural ventilation while also benefiting from plenty of shade.

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

The most redoubtable characteristic of Charles Wright Architects’ work is the strength of one very good idea. Nestled within a grove of tall trees, the two-storey elliptical forms of the Cairns Botanic Gardens Visitor Centre were sheathed in faceted strips of mirrored glass so that the facade performed as a psychedelic artwork, a shimmering refracted re-depiction of its context of trunks and leaves. It was witty, droll and highly entertaining: you couldn’t see the building for the trees. The parti for the (–) Glass House was similarly ingenious: the studio borrowed the orthogonal model of Philip Johnson’s Glass House and transformed it for the tropics by removing the glass walls. That was it. Several other houses have featured extremely exaggerated roof forms, an overtly tropical expressionist gesture that is derived – by several degrees of trans-cultural mutation – from the tribal structures of the Asian archipelagos.

Just as Wright has paid scant regard to the mores of southern-state architecture, so too has he abstained from the prevailing “lightweight” approach of a previous generation of Australian architects working in the tropics. This is not to say that he has deviated from the fundamental climatic and sustainable principles applied by such architects as Troppo, Russell Hall and Rex Addison. Rather, he employs massing and what he refers to as “resilience” to withstand and shield in the harsh environment: he uses concrete, not timber and tin. Wright’s architecture possesses an energized monumentality and a robust tectonic confidence that places him firmly in the lineage of Oscar Niemeyer, Eero Saarinen and John Lautner, and he inscribes his work with a resolutely tropical sense of place and a defiantly self-assured compositional poise that positions his work alongside that of an equally uncompromising South-East Asian peer group (which would include Gary Fell, Andra Matin and Guz Wilkinson, among others).

If ever an architectural commission could be described as a “one-off,” the Stamp House at Cape Tribulation ticks every box. And, in the context of the fragility of its unique context – the eco-diversity of the Daintree Rainforest, as yet unspoilt by humans – it might be suggested that a “one-off” should also be a “one-only.” (Do not fear, by the way; all the other human-made structures in the region are wretchedly timid and transitory.) Given the open-ended nature of the client’s brief and the extraordinary location of the site, Charles Wright Architects had been handed a unique opportunity to design something that is more than a mere house, and the completed structure should really be viewed and understood as a public building rather than a private dwelling.

Stamp House is conceived as a topographical intervention in the tropical surroundings of the Daintree Rainforest.

Set upon the wetlands of the narrow coastal strip beneath the brooding peaks of the Daintree mountain range, a large patch of land on a 26-hectare site has been cleared as the site for a lake, or more accurately a moat, which encloses the concrete mass of the house and protects it from any cyclonic storm surges. The bedrooms and a kitchen are cantilevered over the water as six self-contained pods protruding from one vast communal area, which is roofed but not walled and centred by a swimming pool open to the sky. The client is a renowned stamp dealer and the pool’s eccentric proportions have been derived from the proud profile of “One Pound Jimmy” Gwoya Jungarai, as featured on the classic postage stamp of 1950. Strips of circular indentations in the raw concrete of the external walls continue the stamp references, alluding to the perforations on a sheet, but the overwhelming image is one of retro aerodynamism: the thrusting profiles of the pods appear set for lift-off, the perforations arrayed as rivets in a Lockheed fuselage.

The open-air living area is a community space in the great tradition of tropical vernacular architecture and one that would be impossible to contrive south of Tully. The airflow is balmy and constant, the daylight bounces in from the lake and the pool, and any non-tempestuous rainfall serves as a pleasantly diverting cooling device. Charles Wright Architects has consciously designed a prototype for tropical living, wherein the voids of the section and the incisions in the plan continually generate shade and ventilation and, as a bonus, enable that most sought after of la la land commodities: a venue for unrestrained social interaction. As a symbol of both the demography and the geography of Far North Queensland, the architecture can be viewed as simultaneously hedonistic and organic, but the architect has no delusions as to the real significance of these structural and aesthetic experimentations. Rather than acquiesce to the omnipresent grandeur of the mountains and the velvet splendour of the rainforest that cloaks the slopes, Stamp House reciprocates and reiterates as a topographical intervention – a work of land art, the over-scaled silhouette of which is rendered supremely graphic by its reflection in the waters below.

Credits

- Project

- Stamp House

- Architect

- Charles Wright Architects

Port Douglas, Qld, Australia

- Project Team

- Charles Wright, Justine Wright, Richard Blight, Darcy Shapcott

- Consultants

-

Civic and environmental engineer

MMWC

ESD MGF Consultants

Electrical and mechanical engineer MGF Consultants

Hydraulic engineer Gilboy Hydraulic Solutions

Landscape architect Andrew Prowse Landscape Architect

Quantity surveyor Turner & Townsend

Structural engineer G & A Consultants

Town planning RPS Group

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 4 Sep 2014

Words:

Patrick Bingham-Hall

Images:

Patrick Bingham-Hall

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2014