top and above Views of the Swanston Street facade, showing Christine O’Laughlin’s Cultural Rubble installation.

The Leckie Window (Napier Waller, 1935) from the university’s incinerated Wilson Hall, is suspended in the atrium of the new museum.

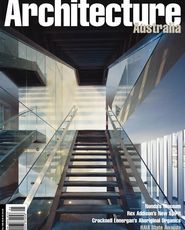

The main stair hall.

| Comment by Leon van Schaik

Nonda Katsalidis is an architect who has found a way to realise his dreams outside

the norms of practice as understood by the profession’s old guard. Dissatisfied by

the abstractions of his undergraduate education, he became a builder. Emboldened

by his engagement with construction, he has forged a career as an architect/

developer of high quality housing in the mould of John Nash and Thomas Cubbitt.

“I am only a commercial architect,” he says as I marvel at the sheer value for

money of the building that is the subject of this review—$2000 per square metre

in 1998! Yet his commercial success has seen our city graced by elegant office

buildings like 300 LaTrobe, and sought-after apartment blocks such as the one in

which I live at St Kilda. I chose it because the building’s little exterior flamboyance

masks a humble rightness of proportion, orientation and scale—and the interior

completely lacks histrionic features. There are no pointy staircases and shard

kitchen counters here.

“I give materials substance. That’s what I’m good at, isn’t it?” Katsalidis asks as

we finish our tour of his renovations and addition to the Ian Potter Museum of Art at

Melbourne University. That simple statement sums up the entire basis of his recent

RMIT University masters-by-project research. For this degree, the vehicle was his

St Andrews beach house—the key that unlocks the endurance of his architectural

ambitions. To Katsalidis, wood is not simply wood; it is every jetty on the Murray,

every pier on the bay. Plaster is not simply plaster, it is the light off the white sand

at Cape Schank, or the light off the ochre sands at Prince Town. Space is not simply

space, it is the holding frame of richly imagined human interactions.

The crucial co-designer of this wonderful project is Frances Lindsay, Director of the

Potter Museum. She has been the Schrader Schroeder to Katsalidis’ Gerrit Rietveld.

She understood the potential of this seemingly tiny site—an insignificant slice

holding a prefab works building behind a hedge fronting Swanston Street—and

recognised that it swelled out into an ‘L’ tucked into the back of the existing gallery.

She sought out an architect who would not alarm the conservative mindset at

Melbourne’s establishment university but who would be unflinchingly contemporary;

with a popular, even commercial touch. In the invited competition she organised,

Katsalidis’ proposal chimed with her vision of this unique institution.

In her imagination, this museum was to be special and exciting, grand and alluring.

Unlike Roy Grounds’ concept for the National Gallery of Victoria, this was not to be

a shopping mall to hopefully unite suburbia seamlessly to the world of art. Instead it

would present contemporary works in the context of their classical origins.

Accordingly, Katsalidis embraced the much-admired white, plaster-like sculpture on

Swanston Street—Christine O’Laughlin’s Cultural Rubble; intuiting that its message

of the best in classical architecture, the most perfect form in the men and women

of antiquity and modern Olympia, and the enduring history of the pot represented

the museum’s mission.

On Level 2 of the building, the almost double-cube proportions of the magnificent

rooms he has so classically won from this tiny site break through to the Victorian

Gothic facade of the existing gallery (now to house the museum’s collection of

archeological pots). The new building is planned about a circulation atrium that

soars to an Aalto-like conclusion in a set of black-finned lantern lights. Within this

space is another relic: Napier Waller’s 1935 stained glass Leckie Windowfrom the

old Wilson Hall (burned in 1952: a Phoenix to this modernist second coming).

Wrapping around the 1940s extension to the Gothic gallery is Katsalidis’ trademark

skin—horizontally articulated, here in a silvery material cut back, “like biting into an apple”, to velvety rusted panels at an upper level where glass, silver, russet and sky

are trapped together in a lyrical grip.

This gallery has six magnificent rooms arrayed in pairs on either side of the atrium.

Three dazzling views release the eye out towards the central city, the exhibition

buildings and beyond to King Lake. When I visited the building, the permanent

collection was being stacked against the walls of the middle-level galleries, where

it will live. An opening through to the gothic spaces of the antiquities collection

suggested a further layering of space. The lower galleries were empty, awaiting

Jenny Holzer’s Lustmondeinstallation in a darkened indeterminacy that their

capacious volume could well deliver. The upper, more rational, galleries seemed to

await drawings. On the top floor, finned windows allow views into the atrium. Here,

designer Cathy Hall has delivered another of her inimitable fitouts, one which

captures those fins and delivers a workhouse capable of supporting the vital project

of this gallery: research.

Frances Lindsay is determined that this museum will demonstrate in every

exhibition that research is at the core of curatorial endeavour, and that we learn

from the excitements of engaging with our world visually. I do hope that an

understanding of our origins—our classical origins—will endure as a consequence

of this remarkable partnership between a university, a gallery director and an

architect with extraordinary empathy.

Lindsay talks of the successes of the Frick in New York and the Picasso Museum in

Paris; galleries which invite both exploration and discovery. She identifies the

limitation of Heidi: that the space reveals all at a glance. She talks of the

disappointingly Lilliputian qualities of the NGV and the National Gallery of Australia,

where (like Quai d’Orsay), some spaces are too big, others too small. Exploring her

gallery, I sensed a whiff of the Whitney, and of Peter Zumthor’s astounding

Kunsthalle at Bregenz. But only a whiff. At $10 000 sq m, those institutions play a

more sophisticated game—not necessarily a better game. There is also a faint

odour of the Museum of Modern Art (New York, not Heidelberg); especially when

you discover that Brunettis will operate the ground floor café. The café plan is in the

form of a cut through the fluting of a classical column—inspired, says Katsalidis, by

the external frieze. The concave flutes of the glazing give a reflection-free view into

the side space, colonising it completely.

Be that as it may (to paraphrase George Moore reviewing Ludwig Wittgenstein’s

Oxford doctorate), this gallery is certainly a match for the Museum of Contemporary

Art in Sydney, and that is good for the city-state of Melbourne and for art in

Australia. It’s a long time since I felt so positive about the intellectual life of this city,

and I believe that Katsalidis contributes an architecture that is unflinchingly neo-modern

to accompany the muscle of the gallery’s program under Lindsay. It is

certain that this building will be essential to the plausibility and success of the next

Melbourne International Biennal. Even Juliana Engeberg, the highly skilled Biennal

director, would have had difficulty mounting this event in the decay of the NGV from

Grounds’ misguided Art Mart ( paceAlsop, courtesy Lindsay) to Bellini’s kitsch

gondola-eatery.

Unlike that sad tale of cargo cult design adulteration—but in the same way that

Zumthor’s Kunsthalle is all about West Austria and East Switzerland—Katsalidis’

Museum of Art is about the materiality of Victoria. Everyone anywhere who engages

with their own province in a metropolitan way will take heart.

Professor Leon van Schaik is Dean of the Faculty of the Constructed Environment at

RMIT University Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of

Melbourne, Melbourne

Architects Katsalidis—project team Nonda

Katsalidis, Bill Krotiris, Holger Frese, Robert

Kolak, Rainer Strunz, Keriran Boyle, Chris

Godsell, Jackie Wagner, Barbara Moje, Luisa Di

Gregorio, Kei Lu Cheong, Adrian Amore, Lisette

Agius, Donna Brzezinski, Marius Vogel. Client The

University of Melbourne. Builder Probuild.

Structural Engineer Scott Wilson Irwin Johnston.

Services Engineer Simpson Kotzman. Building

Surveyor Philip Chun & Associates. Quantity

Surveyor Donald Cant Watts Corke. Acoustics

Carr Marshall Day.

|