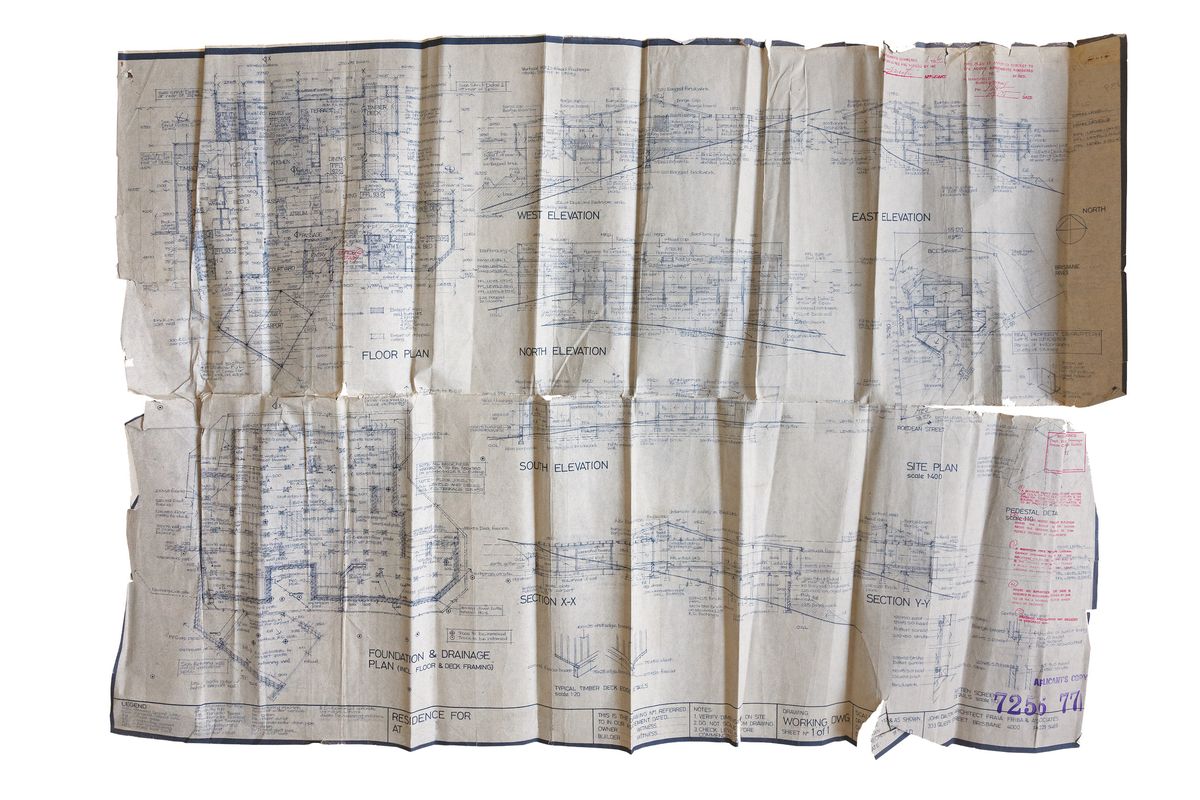

Sun + Life + Useful Form = Architectural magic”1 was a formula given by renowned Brisbane architect John Dalton (1927–2007) to students of architecture in 1961. It highlights a set of preoccupations contributing to a style instantly recognizable to Brisbane’s architectural cognoscenti as the “Dalton house,” characterized by dark-stained timber and white walls across which sunlight and shadows play. These preoccupations are evident in the Dalton house revisited here, located in Brisbane’s western suburbs and completed in 1978. Designed in the later part of his career, it is far from a simple iteration of his successful formula. In many respects it is the culmination of architectural investigations over the previous twenty years. The trademark palette of materials is present, but deployed in a way that differs from the typical extended plan arrangements Dalton is noted for. In this instance, the need to site the house above historical flood levels while maintaining optimum orientation for sun and cooling breezes was a factor – design for climate being a particular concern of Dalton’s. Also evident is his developing awareness of how the immediate setting can be engaged to contribute to a memorable architectural experience.

Dalton’s clients, both medical practitioners, commissioned John Dalton Architect and Associates in 1977 after reading a magazine article that cites the architect. The article includes comments made by Dalton at the very beginning of his career, linking design for climate to its expression and experience, and is illustrated with images of work completed over the intervening years, showing the seductive play of light and shadow at building edges. Desiring something “practical” and “not too big,” the owners now describe their home as a “marriage of beauty and practicality” and have resisted altering it in any way.

View through the living spaces to the sunlit landscape beyond. Artwork: James Willebrandt.

Image: Dianna Snape

The site presented Dalton with his first test of priorities. An oddly shaped block at the end of a cul-de-sac, it falls steeply away at the east to the Brisbane River and at the north to a treed gully. Rather than directly addressing the river, the house is oriented to maximize its northern aspect and connection to site while maintaining long views diagonally downriver. The question of how far down the site to place the house was resolved by locating the principal living platform above the disastrous 1893 flood level. Consequently, the house nestles into its site and is almost entirely concealed from the street above. It addresses the wall of dense remnant vegetation in the reserve to the north across a sunlit garden, forming a private realm removed from its suburban surroundings.

Programmatically, the house comprises three zones – a parents’ wing, a children’s wing and a shared living wing – organized into a stumpy T-shaped plan and conceived as a series of linked platforms following the fall of the site. Despite being located as far down the site as flood levels would allow, the resultant plan is problematically deep. Climatically responsive design typically dictates plan arrangements involving single banked rooms. Here, the problem is addressed with courtyards providing light and ventilation.

There are three courtyards in all. Internally, each has a particular character and an important additional role in articulating pathways and territories. One courtyard provides the main entrance to the house and is an extension of the garden between the children’s and parents’ wings. Another, a pebbled garden lined with white fibrous sheeting and dark timber cover strips, and containing a tropical birch and a contemporary sculpture, has a distinctly Japanese air. It lights the living room and kitchen, which, like the kitchen of Dalton’s own house in Fig Tree Pocket (1960), is located in the centre of the house. A courtyard “void” belongs to the service zone. It is a double-height space wrapped by a timber drying deck at the upper level, allowing light and views into a workshop level below and enabling kitchen and workshop occupants to maintain contact.

One of three courtyards, this pebble-filled area features a contemporary sculpture and has a distinctly Japanese air. Sculpture: Daniel Templeman.

Image: Dianna Snape

The dwelling is experienced as a sequence of spaces descending from street level through the house to a flyscreened terrace perched above the garden on the river side and noted on plans as the “lanai.” As you step down past living spaces, long views opening through the house to places in the sunlit landscape beyond are balanced by compressed views within and the thoughtful placement of key artworks. The screened lanai, perched at the north-east corner of the house, is a magical space whose development can be traced from Dalton’s earliest houses and which is encapsulated in Harry Sowden’s iconic photograph of the atrium space of the award-winning Wilson House (1964).2

On backtracking through the house and down to the garden that was designed by Jeremy Ferrier Landscape Architects, the visitor discovers sitting spots retained against the hillside and offering views to the river. When viewed from here, the house presents as characteristically Dalton – a framed timber box propped off brick piers and retaining walls. But here, retaining walls extend into the garden to appropriate territory. More than previous houses, this Dalton house is a marriage of house and garden into a unified whole. Pergolas and screened terraces under deep overhangs are more consciously suggestive of cool, verandah-like spaces behind.

Offering views framed by a fringe of pergola, the “lanai” – a light-filled, flyscreened terrace – is a “magical space.”

In his address to students in 1961, Dalton encouraged consideration of the experiential dimension of architecture: “… for us, life in the sun is a reality, and we who build in the sunlight sense the joy of space and light. It is our delight. The magic of shade and shadow capture our senses and direct us towards our purpose, which is to dispense comfort and happiness through useful form …”3

To a very great extent, this Dalton house fulfils the promise of Dalton’s earlier rhetoric. It is informed by a set of interests that extend beyond the careful composition of formal elements in sunlight to the making of delightful settings that both invite occupation and are expressive of it.

John Dalton

John Dalton ( 1927–2007) was born in Yorkshire, England and immigrated to Australia in 1950. He trained in the offices of Frank Costello, Cook and Kerrison; Hayes and Scott; and Theo Thynne and Associates before registering as an architect in 1957. He and Peter Heathwood established a short-lived partnership after winning a competition for the Plywood Exhibition House in 1956. Dalton then established a solo practice in 1959, and over the next thirty years designed a significant collection of residential and institutional buildings. His approach may best be encapsulated in his own catchphrase quoted in Architecture and Arts , 1961: “Sun + Life + Useful Form = Architectural magic” (taken from The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture, entry by Peta Dennis).

1. An extract from an address to the Queensland Architectural Students Association by John Dalton, reproduced in The Australian Journal of Architecture and Arts, August 1961, p. 46.

2. Harry Sowden, Towards an Australian Architecture (Sydney and London: Ure Smith, 1968).

3. John Dalton, address to the Queensland Architectural Students Association, p. 46 .

Source

Project

Published online: 14 May 2015

Words:

Elizabeth Musgrave

Images:

Dianna Snape

Issue

Houses, February 2015