The southern facade of Swanston Square bearing the image of William Barak and titled “Portrait” (as if it were a work of art in its own right) has been the subject of heated debate since it was first proposed by ARM Architecture in 2006. Portrait’s ambitions, consequences, authorship and legitimacy have been vociferously argued across informal and formal media channels, including some in which architecture is a novelty. So thoroughly has Portrait been dissected that reviewers have turned to weighing up the various arguments made, a kind of meta-criticism rarely visited upon Australian architecture. In all accounts, though, the building onto which Portrait is irrevocably grafted is elided. Swanston Square is present only as the economic and material substrate of a monument to local Indigenous history. For detractors it is an inappropriate coupling, or as Christine Hansen puts it: “To place high-end CBD real estate and an image of the most famous of nineteenth-century land rights activists in the same frame is a cruel juxtaposition.” 1 The site, too, has been found wanting by critics of Portrait because of its past history as a brewery. In their promotion of Portrait the architects have tended to speak of the site primarily as a place of prospect from which Portrait can stare down Swanston Street to the Shrine of Remembrance. Swanston Square’s apartments and the ground on which it is built have become an irrelevance, ignored in much the same way that convention demands we ignore the easel on which the painting rests or the plinth below the bronze bust.

Swanston Square is, however, more than just a plinth for Portrait. It is a live setting for contemporary struggles between the city as the locus of civitas and the city as financial machine. Hansen’s reference to “high-end CBD real estate” operates here as both a symptom and a call to arms. Lurking behind debates about the value of Portrait are anxieties about who exactly is buying and taking up residence in the 536 apartments behind Barak’s features. These anxieties are not, as they might at first seem to be, only about class and income inequality. They are also about race, nation and the global economy. In 2012, residential real estate investment from abroad was $17.16 billion and growing; it is Australia’s largest industry sector for foreign investment. 2 Swanston Square is designed to take advantage of this market and is one of many similar projects in Melbourne and other Australian capital cities. In the mainstream media, the greatest anxiety is reserved for Chinese buyers whose frustration with restrictions on owning investment properties in other countries are perfectly assuaged by generous tax incentives that come with buying off the plan in Australia. It is, I suspect, these buyers that are the targets of gibes about the building’s “luxury clientele” that pepper discussions about Portrait.

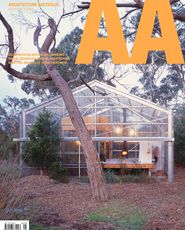

Apartments include built-in wardrobes, cabinets and kitchen counters.

Image: Shannon McGrath

It is not luxury, though, that lies behind Barak’s visage. Swanston Square’s residents will largely be students, be that as tenants or owner-occupiers. Federal and state laws on foreign ownership require that one of the purchasers occupy the new property for six months. This restriction suits parents of international students, who get to invest in property and their children’s education at the same time. It’s a big market. Australia’s number of full-fee-paying overseas students as a proportion of the total population is the highest in the world. The attractiveness of our tertiary education sector reflects the quality and diversity of our degrees, but it is also the case that Australian universities are financially competitive. They have to be, for in the face of diminished government support they cannot function without the fees paid by overseas students – these account for as much as a quarter of some universities’ revenue. The symbiotic relationship between the property market and the educational export industry is well understood. When the Abbott government moved early this year to introduce a minimum $5000 fee for foreign nationals to have their applications to buy property assessed by the Foreign Investment Review Board, the Australian Financial Review declared it “could harm the education sector.” 3 Others fear that foreign investment is driving property prices beyond the means of “ordinary Australians.” There are many contributing factors to Australia’s “property bubble,” but the fear-mongering of the Abbott government around immigrant invasion means that many Australians are confused as to whether to feel gratitude towards international students for propping up our tertiary sector and our economy, or resentment for their superior real-estate purchasing power.

Many universities have embarked on the construction of student residences of high quality and amenity, but for universities in CBD locales the costs and risks are too great and the provision of student housing has been left to the private market. For the poorer students who end up sleeping four to a room or, worse, “hot-bedding,” Swanston Square may well seem luxurious. Each bedroom has its own (identical) bathroom. It is clean, new, safe, air-conditioned and superbly convenient for RMIT University, the University of Melbourne and a host of private education providers. The lift lobbies are well lit and decorated in an up-market, streetwise mode that knows its youthful clientele, much like the gymnasium and retail outlets on the ground floor. The topmost floor includes the sort of amenities attractive to a younger clientele – barbecues, large tables and jacuzzis.

In addition to sweeping views of the city, the Sky Deck has spas, kitchen facilities and seating, making it an ideal place for residents to entertain guests or meet with other residents.

Image: Shannon McGrath

But if luxury also means spaciousness, fine materials and personal tailoring, then these apartments are far from that. The minimization of floor space and the maximization of yield to the developer have been the overriding architectural determinants. Over a long period of design, and with a roller-coaster economy, the apartments were successively tightened. Starting at just under forty square metres, bedrooms are as small as nine square metres and many have no external windows. Such micro-apartments are legal in Melbourne, but hardly ideal. The two-bedroom apartments on the acute north-west corner are the worst, for although they have a kitchen bench it is essentially located in the corridor leading to the bedrooms. There is no space for a dining table, no living room and the balcony is accessed through one of the bedrooms. The views from many of the apartments are superb but the balconies are not large enough to do more than stand, viewing. Jesse Judd, the project architect for ARM Architecture, has made the best of a fat floor plate. Vivid colours and graphic surfaces enliven internal corridors and foyers. Lack of street frontage has been cleverly countered by linking the entry through to Swanston Street via a smartly restrained refurbishment of the heritage Maltstore building. From Victoria Street, entry is through what was previously a dreary, dead-end space alongside the RMIT Design Hub. Above, the spelling out of “Wurundjeri I am who I am” in braille using circular metal discs is as much a witty retort to its sequinned neighbour as it is a caption. Despite these valiant efforts and abundant design skills, the architects have not been able to transcend the economic rationale. Those particularly unsatisfying corner apartments register that moment where the architects’ influence faltered in the face of dehumanizing financial logics – just as Portrait is that moment where the architects prevailed.

Swanston Square adds 536 apartments to the area and is located near a number of universities.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Grocon’s support of the Barak portrait could be seen as a marvellously successful decoy that has distracted critics from the fact of a squat block of pedestrian apartments. I doubt that is the intent. Grocon is one of the more civic-minded developers. We should not forget that in Melbourne Grocon built a Common Ground facility on Elizabeth Street for formerly homeless people at cost for which the company won the Mercy Foundation’s annual Social Justice Award in 2010. 4 Additionally, it must surely have been tempting to abandon Portrait and avoid further controversy after the project became mired in industrial and legal action following the collapse of a wall on site in 2013, which led to the deaths of three pedestrians. On the other hand, it is to mistake the nature of such corporations if Portrait is viewed as an act of selfless, noble, cultural patronage. We should look instead at how it is that as a society we came to be so indecently reliant on the complex interests of private corporations for acts as important as commemorating Aboriginal history and supporting Aboriginal people in the present. Alongside debates about Portrait, a serious critique of what it means to give over the city to private interests in the context of globalization and neoliberalism is needed. And we should keep our watch over the site as steady as William Barak’s, for there is more to come. In 2014 Grocon sold sixty-six hundred square metres of the CUB site for $58.3 million to mainland Chinese developer Xiang Xing, 5 one of many offshore developers from China, Singapore and Malaysia that have recently purchased development sites with planning permits in Melbourne. Grocon sold the heritage-listed refurbished Maltstore to a private investment syndicate from Singapore in March 2015. 6

1. Christine Hansen, “Melbourne’s new William Barak building is a cruel juxtaposition,” The Conversation, 19 March 2015, theconversation.com/melbournes-new-william-barak-building-is-a-cruel-juxtaposition-38983 (accessed 25 July 2015).

2. Foreign Investment Review Board, Annual Report 2012–2013, 29, firb.gov.au/content/Publications/AnnualReports/2012-2013/_downloads/FIRB-Annual-Report-2012-13.pdf (accessed 25 July 2015).

3. Chris Tolhurst, “Foreign Investment Review Board new fee regime threatens lucrative overseas student market,” Australian Financial Review , 25 March 2015.

4. “Australian Construction Company Wins Social Justice Award,” ProBono Australia website, 19 May 2010, probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2010/05/australian-construction-company-wins-social-justice-award#/ (accessed 4 August 2015).

5. Simon Johanson, “Project slowdown hits Daniel Grollo’s Grocon,” The Sydney Morning Herald , 18 November 2014.

6. “Sale signals New Lease on Life for Historic Melbourne Maltstore,” Corporate Real Estate website, 11 March 2015, news.corporaterealestate.com/245/sale_signals_new_lease_on_life_for_historic_melbourne_maltstore (accessed 25 July 2015).

Credits

- Project

- Swanston Square

- Architect

- ARM Architecture

Australia

- Project Team

- Howard Raggatt, Stephen Ashton, Andrew Lilleyman, Jesse Judd, Sophie Cleland, Amber Stewart, Ben Tole, Victor Bredin, Lee Lambrou, Paul Buckley, Jenny Watson, Laura Burley, Lily McBride-Stephens, Alex Wilson, Louisa Macleod, Matthew Bird, Matthew Pieters

- Consultants

-

Acoustics

Marshall Day Acoustics

Building surveyor Philip Chun & Associates

Developer Grocon

Documentation Webber and Associates

Electrical and mechanical engineer Norman Disney Young

Facade subcontractor MouldCAM

Fire engineer Aurecon

Head contractor ProBuild

Heritage Lovell Chen

Hydraulic engineer CJ Arms & Associates

Structural and civil engineer Aurecon

Vertical transport consultant WSP Group

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2015

Category Residential

Type Apartments

Source

Project

Published online: 25 Nov 2015

Words:

Sandra Kaji-O'Grady

Images:

Peter Bennetts,

Shannon McGrath

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2015