After a summer filled with the savage imagery, heat and scent of bushfire, The Architecture Symposium, Brisbane, held on 13 March 2020, offered the lure of a day of intellectual and emotional succour: eight speakers reflecting on the theme of water, refracting their architectural output through its unifying, yet mutable, lens.

Realrich Sjarief of RAW Architecture commenced the symposium by presenting a series of projects from his home city of Jakarta, a pressured delta city subject to the pernicious effects of water through periodic inundation. RAW responds to this urban precariousness with a dexterous and mystical pragmatism – drawing deeply on the lessons of unity and harmony with place from Javanese culture and uniting this with an experimental attitude to basic, readily available construction materials.

Bamboo Theatre by DnA Design and Architecture, whose director Xu Tiantian presented remotely from Beijing.

Image: Wang Ziling

Sjarief described the Alfa Omega School project, where RAW had been tasked with constructing a school campus on a swamp in Tangerang city within a five-month period. A sense of adaptability necessarily informed architectural decision-making at every level. The first move was to construct a bridge that enabled the transportation of material and tools to site. The second was to develop a tectonic response that was able to unite the speed and strength of steel with the durability of concrete and the local knowledge, availability and economy of bamboo. There is nothing perfunctory about this architectural pragmatism – fine hybrid bamboo structures in undulating forms that aid in the resistance of wind pressure, teamed with permeable facades and pavilion forms, are lifted above the flood level to create an utterly engaging learning environment.

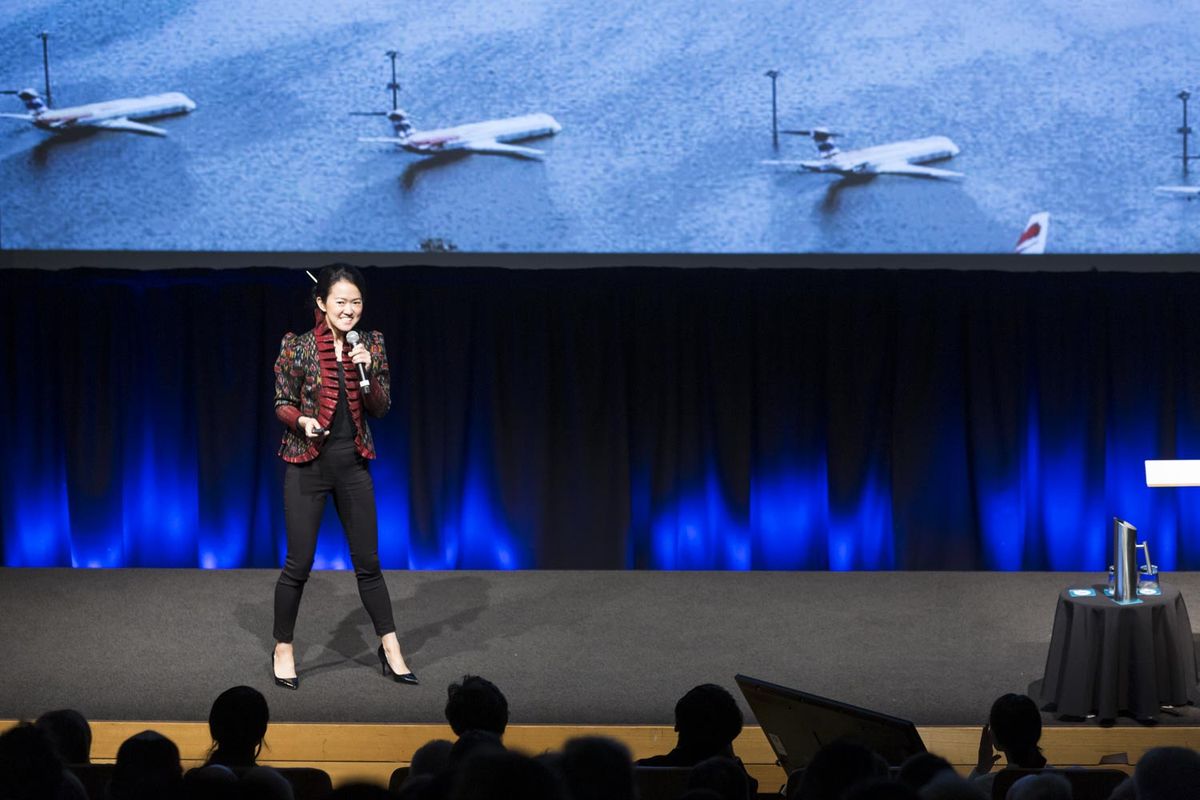

Landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom, from Landprocess, shared lessons from Bangkok – a city occupying a shifting river delta, with water a threat from both its southern water interface and landlocked northern edges. Evocatively, Voraakhom described its resulting character as “amphibious,” but also reflected on the emergent social injustice of climate change. During the recent floods, the city of Bangkok was protected, at the expense of surrounding settlements – a political calculation with the most acute of human consequences.

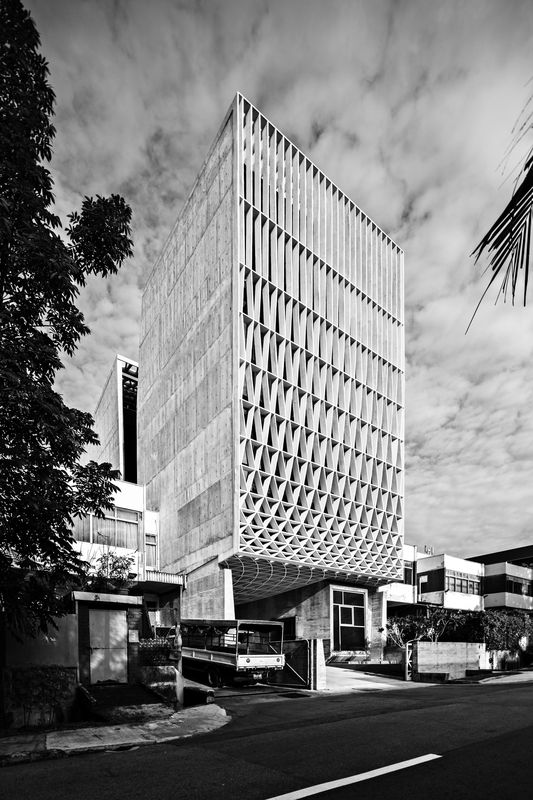

A Simple Factory Building by Pencil Office.

Image: Kenneth Choo

Voraakhom’s landscape works are a reflexive response to the city’s inescapable landscape condition. She chooses to operate on the elevated planes of urban roofscapes and uses architecture to generate Bangkok’s absent topography. At Chulalongkorn University Centenary Park, Landprocess worked with architectural practice N7A to incline a parkland space sculpted by architecture, which collects, slowly releases and treats water. The artificial topography channels floodwater into underground tanks with a staggering capacity of 3.8 million litres. Overflow is released and percolates through a series of treatment ponds that make engaging recreation spaces – herb gardens, meditation areas, reading spaces and wetlands. Distinguishing itself from the cosmetic roof-garden spaces that proliferate in every so-called “global city,” this project is anchored in the city’s authentic ground plane. It unfurls from the park along two major axial urban boulevards, where traffic was reduced, pedestrian zones increased, and linear rain gardens formed that invite the wider urban quarter into this sumptuous, green sanctuary.

Tokyo-based Takeshi Komada feigned bemusement about finding a direct relationship between his architectural production and the theme of “water,” before staging an elegant, intellectual sleight of hand. Constructing an analogy that related the movements and gathering of people to the circulatory cycles of water, he raised a thoughtful discussion about the ways that urbanity can support community and topophilia (the creation of an emotional link between people and their environment).

Komada demonstrated this through a presentation of two urban apartment buildings on the same site, created 18 years apart, for which he was both architect and client. The first, completed in 2000 and home to his family, occupies half of the site. The second, a mixed-use building completed in 2018, occupies the remainder of the urban block, which has become an intimate community hub. Even in a tiny linear space between the buildings an authentic communal spirit can flourish, with home, work, baking, markets, craft and workshops tightly coalescing . Not to mention the extraordinary accomplishment of the architecture itself – the building’s porous cellular arrangement that effortlessly accommodates shifting uses over time, in an intimate and tactile spatial frame elaborated with very few additional elements.

CU Park by Landprocess.

Image: Supplied

Despite presenting remotely, Beijing architect Xu Tiantian, of DnA Design and Architecture, had the auditorium utterly spellbound by the Songyang Story. Tiantian’s project took us to the Chinese countryside – a collection of projects in the Songyang County, situated in a mountainous landscape traversed by the Songyin River. The Songyang Story comprises more than 20 sublimely lyrical and highly specific interventions in rural villages, linking tourism to manufacturing infrastructure and community facilities. For example, the brown sugar factory in Lishui provides new facilities for sugar production in the winter months – and, at other times, is available for community uses such as puppet shows, tea gatherings and film screenings. The factory is almost operatic in its spatial sensibility, turning manufacturing into performance theatre.

The project is seemingly endless – tofu factories, tea plantations, pine resin factories, fishing pavilions, bridges and memorial halls, each precisely judged and exquisitely realized. Most importantly, these projects are not romanticized rural adornments, but strategic economic interventions that have transformed the daily lives of their communities. Each has been retrospectively monitored and the increases in tourism, visitation and income for villagers documented.

The transition from this presentation to that of Philip Cox, from Cox Architecture, Australia was one of extreme contrast, taking us from rural China to its largest cities and the recently completed National Maritime Museum of China near Tianjin. Cox displayed enthusiasm, curiosity and engagement in relaying the practice’s experiences of working in China. He showed a range of work across Australia, Asia and the Middle East, where the practice has engaged with projects on, or near, water. The scale and character of projects like the Kuwaiti Island settlements and the maritime museum were difficult to reconcile with the finer grained approach prevailing in the broader symposium – but were an important reminder of the relentless commercial and economic momentum propelling the region’s broader architectural oeuvre.

National Gallery of Indonesia by RAW Architecture.

Image: RAW Architecture

The final session, with Erik L’Heureux of Pencil Office, based in Singapore, transformed water to vapour, as L’Heureux passionately recounted his lived experience of the equatorial sky – one of clouds, driving sheets of rain and hazy edges, pregnant with humidity. He showed projects that embrace the particularity of these conditions and reject what he perceives as a growing sensibility that seeks to tame them in favour of the clarity of a temperate climate and conditioned air. A Simple Terrace House is a beautifully considered row house with a porous section that is selectively permeable to air, vapour and water. Its porous sectional form controls climate passively as its palette of concrete and mesh bleeds into the gauzy grey Singaporean sky.

Julie Stout from Mitchell Stout Dodd Architects, Aotearoa (New Zealand), brought cautionary tales of water as contestable space. She jolted us back to beginnings with an arresting image of the Pacific Ocean and islands at the centre of our region, with the larger land masses forming secondary, peripheral edges. This story traced a devastating history, from water at the centre of Pacific life, with its mythical spirits’ inhalations and exhalations visible in the tidal movement of the ocean, to invasion, colonization and the Treaty of Waitangi; a dispiriting arc of dislocation, from holistic systems binding people to place to those based on ownership, exclusion and rapacious abuse. The recent manifestation of these forces is evident in Stout’s five-year battle to halt an aggressive expansion of the Port of Auckland into the harbour. Her campaign’s rare victory in the High Court of New Zealand gave the population time, and a process, to collectively reconsider the way that Auckland might heed the lessons of its past to move forward with greater and more ethical purpose.

Gurjit Singh Matharoo, from Matharoo Associates, based in Ahmedabad in western India, concluded the day’s presentations by bringing us back to the essential qualities of water, with a heady mix of spirit, tectonic candour and humour. Each of Matharoo’s projects was introduced by sumptuously coloured watercolour drawings evoking the dynamism of life and place suffusing it.

Matharoo related seven projects to seven qualities of water: cool, sustain, indulge, soothe, spirit, aspire, utility. Under the theme of spirit, he described the Ashwinikumar Crematorium in Surat, located adjacent to the river Tapi. The proximity of the complex to the river was significant. In India, rivers are considered goddesses – they are sites of purification and ritual, and often bring the possibility of flooding. He described the widening of the project to ally water with its companion elements – exposing the earth through cuts in section, fire through cremation, air through the breeze that permeates open courts and circulation spaces, and water as the final element, where mourners are invited to engage physically with the river waters in completion of the funerary cycle.

The spare power of the projects was in danger of being upstaged by Matharoo’s side-splitting accounts of their construction. After a quick glance upwards and an introductory “as sometimes happens in my country…,” there were stories of critical structural elements delivered to site three months late, civil contractors winning tenders without understanding they were being asked to construct a building, the variable results of unskilled form-workers and misunderstandings regarding the application of sand-blasted finishes (which saw them taken to polished stainless steel instead of defective concrete). All were hilarious, but also hinted at an impressive level of adaptability and resilience that has been developed in the face of adversity, great and small.

Brimming with the energy and inspiration of the day’s insights, we left the symposium only to confront news of the worsening international pandemic. First fire, then water, and now ether imperils us, through contagion. A period of intense reflection is being foist upon us.

So many of the symposium’s speakers recounted serious environmental disruption as an accepted part of the annual and seasonal rhythms of their cities. Their response has been defiant and spirited – to develop strategies of agility, humility and reconnected-ness with old spiritual knowledge of culture and place, and ways of realizing work that use minimal means, deployed with intelligence, wit and élan.

In a time when we will all need to tread more lightly, in spirit and in deed, how very fortunate we are to cling to the bottom rim of this utterly extraordinary region.

The Architecture Symposium, Brisbane, was held during the Asia Pacific Architecture Festival, a collaboration between founding partners Architecture Media (publisher of ArchitectureAU.com) and the State Library of Queensland. The symposium was supporter by major partners Cement Concrete and Aggregates Australia, and Planned Cover, university partner Abedian School of Architecture at Bond University, venue partner State Library of Queensland, and hotel partner Ovolo.