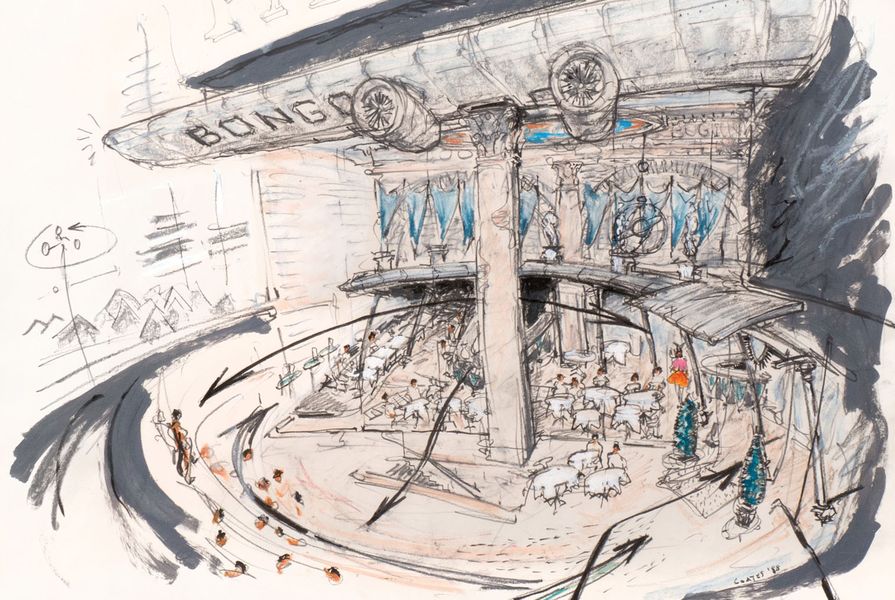

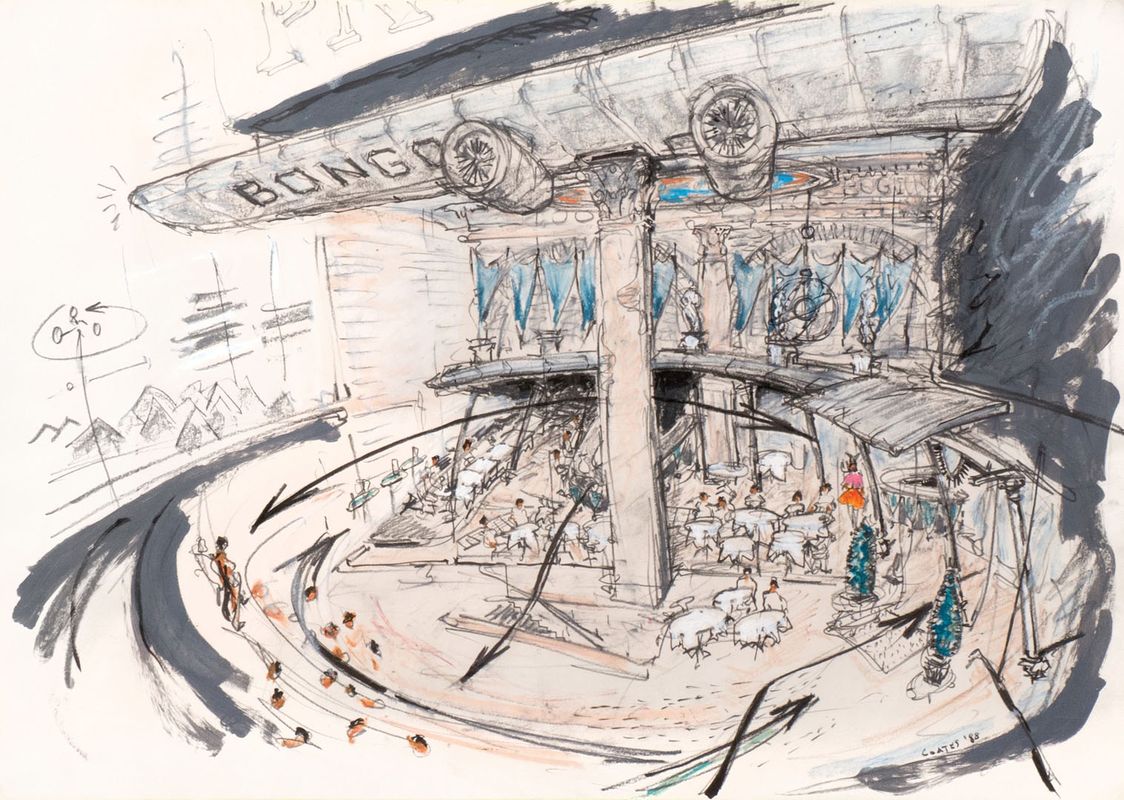

Decades have passed since architectural monographs were hot property. In Tokyo in the late 1980s, you could stand in bookshops and watch piles of books a metre high disappear in a flurry of hands as staff replenished the piles from loaded trolleys. Such frenzied buying is not often seen by Australians, other than on Christmas Eve at South Melbourne Market, when staff shovelling prawns out of lorries fail to keep pace with the demand inside. Nowadays, publishers – with very rare exceptions – produce monographs at the expense of the architects that they feature, even if this embarrassing fact is masked in various kinds of contra dealings. In the 1980s, the demand was fuelled by a public newly fascinated by the glamour of architecture – a period when Nigel Coates could buy up loads of junk on the Portobello Road in London, ship it to Tokyo and create dream worlds such as Caffè Bongo (1986) or The Wall (1990) for a delirious public.

A few economic downturns later, and only El Croquis and possibly GGili (2G) produce quasi-monographs that are editorially driven, staking a claim for a particular architectural vision. Monographs today are often advertising, passed freely to existing and potential clients, and only rarely are they acts of reflection, stepping stones to a new surge of creative practice or capstones seeking to define the contribution of a long period of practice. In the former group, one hopes for a full record with plans, elevations, sections and clear descriptions of context, and a few sympathetic essays by friends. You hope to avoid the over-generous scholar who compares your work glowingly to the Renaissance master that he studies – cringingly embarrassing, that! – yet it has happened. All too often in this cluster, however, all that you get are carefully composed photographs that remove all possible contamination by people or places. A tabula rasa purity that shows up just how vacuous the whole endeavour has been.

Reflective monographs are often structured in a similar way, but the range of essays is wider and not all criticism is suppressed. A few essays by people from within the discipline and from adjacent disciplines serve to suggest that the practice is culturally significant beyond the sphere of architecture. Photos by one of a small stable of architectural photographers are used and the images are usually very, very clean. Only rarely is a critic invited to have free rein – as I was with a wholly authored monograph. Here, there was a set of surprising discoveries and some new knowledge was generated. Recent Melbourne monographs (published and as-yet-unpublished – John Wardle Architects, Lyons Architecture, Edmond and Corrigan, ARM Architecture) document in innovative ways – both graphic and intellectual – extraordinary bodies of work and incorporate critical reflections by critics and the firms themselves. These, too, are significant contributions to knowledge.

Motives for making them differ, but what this small flood of monographs will undoubtedly do, by virtue of their nearly simultaneous appearance, is engender debate about the nature of architectural practice in Australia today. To what extent is it idea-driven? Is it more to do with securing effective delivery of projects? Or has its innovating mission succumbed to the professionalization of risk avoidance? How consciously political is it? Are the ideologies of realism, idealism or populism evenly spread, or has pragmatism swept the board? What modes of designing and manners of production prevail? Is abstraction and mathematical modelling advancing or receding? How are practices prototyping, if at all? Or are they all comfortably doing what has always been done? Who designs by focusing on process, who seeks out an encompassing figure and designs towards that? Who ducks the aesthetic challenge altogether? Who is at the vanguard of firmness, who of commodity, who of delight?

This article, published in Architecture Australia’s Mar/Apr 2014 issue, introduced four reviews of recently published architecture monographs:

Minimono: Paul Morgan Architects (reviewed by Carey Lyon)

Multitudes: Hassell 1938–2013 (reviewed by Leon van Schaik)

Exchange: Collaboration, Convergence, Conversations (reviewed by Sam Spurr)

Architecture as Material Culture: The work of Francis-Jones Morehen Thorp (reviewed by Elizabeth Farrelly)

Source

Discussion

Published online: 21 May 2014

Words:

Leon van Schaik

Images:

courtesy of Nigel Coates Studio

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2014