The name Robin Boyd should be known to every Australian architect. The Melbourne architect was prominent in the postwar era, but he was many decades ahead of his time. Boyd was a proponent of an environmentally sensitive and locally specific adaptation of modernism, a teacher, a writer, an ambassador for the profession and a political agent committed to the advocacy of good design. Boyd was awarded the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’1 Gold Medal in 1969 in recognition of “the many distinguished works of architecture and architectural writing for which he has been responsible.”2

Architect Robin Boyd.

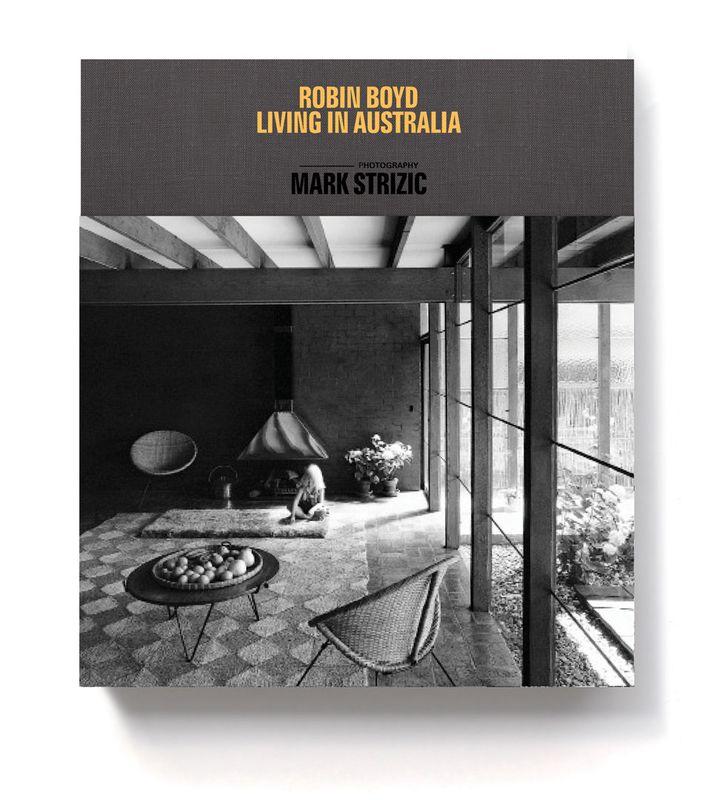

Though his design career encompassed a number of larger works, including churches, colleges, some of Australia’s first motels and the Australian Pavilion for Expo 67 in Montreal, Boyd’s enduring focus was the residential sphere. Working predominantly with lower-income families, his houses were the result of an egalitarian commitment to accessible architecture. In a country staunchly and inexplicably devoted to housing designs poorly suited to its culture, climate and construction technology, Boyd utilized effective design, simple materials and new prefabrication methods to provide cost-effective, high-quality buildings.

Boyd’s work, which comprised two hundred or so completed houses, was characterized by restrained materiality, a sympathetic engagement with the natural landscape and a warm humanity. These were also polite buildings, as mindful of their neighbours and streetscapes as they were their internal amenity. A half century before the Victorian ResCode planning scheme (2001) enshrined in regulation the need to consider a building’s impact on its surrounds, Boyd’s work sought sensitive solutions for both his clients and the built environment.

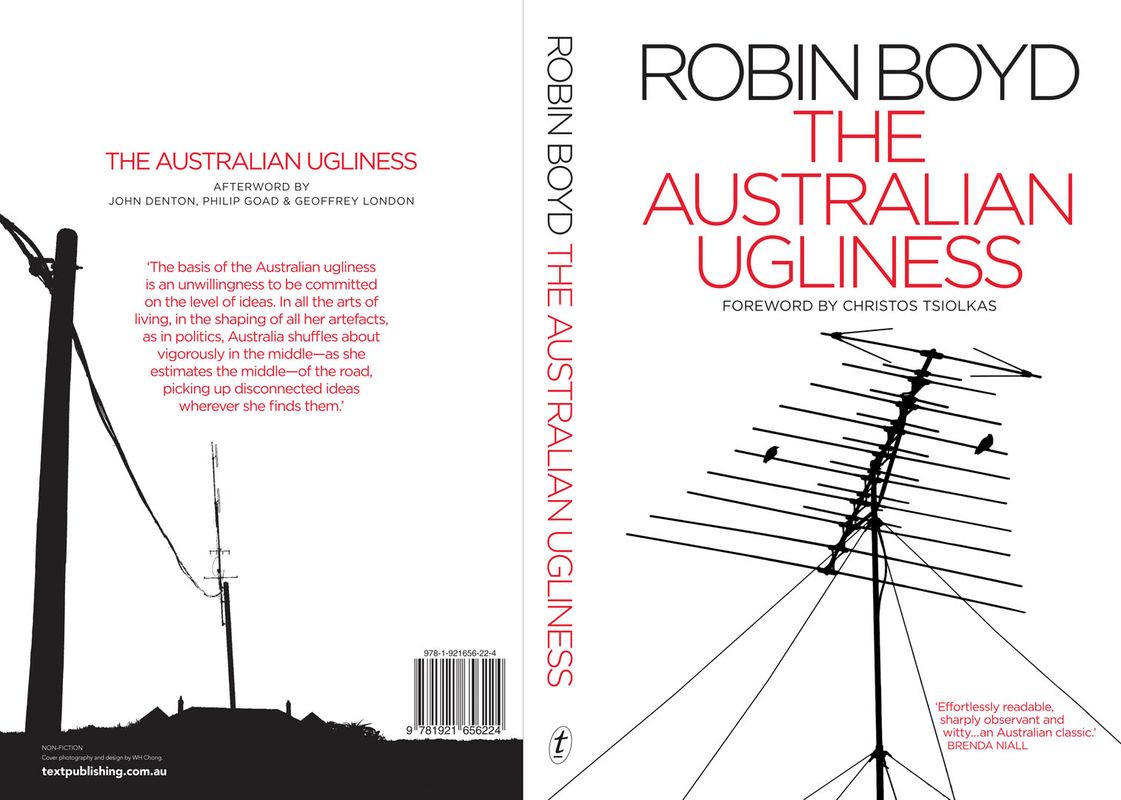

As indicated in the Gold Medal citation, this approach was reflective of a broader dedication to good architecture and the propagation of its values to all Australians irrespective of wealth or background. In addition to his residential work, Boyd is remembered for The Australian Ugliness (1960), a timeless attack on the fickleness of Australian cities and one of nine books he had published in his lifetime; his part in establishing the National Trust of Victoria in 1956; and his role as founding director of the Small Homes Service, a collaboration between the Institute and The Age with which he was involved from 1947 until 1953.

More than that of any of his contemporaries, possibly more than that of any Australian architect since, Boyd’s engagement with architecture and the built environment extended far beyond the confines of his individual projects. The Small Homes Service and associated lifestyle articles in The Age influenced a large part of an otherwise design-illiterate public; his lecturing posts at universities here and abroad influenced the next generation of architects; and his publications have continued to influence every generation since. If I were to distil all of these activities, and the values behind them, into a single phrase, it would be “to expose the general public to the benefits of good architecture.”

Since 2005, this philosophy has taken formal shape in the Robin Boyd Foundation, a not-for-profit organization originally established by the Institute and the National Trust, and committed to the continuation of Boyd’s legacy. Beginning with the purchase of Boyd’s own house in Walsh Street, South Yarra, the Foundation now runs half a dozen open days a year, providing access into modernist and contemporary houses, and runs seminars from contemporary architects and their clients at Walsh Street. It also produces annual publications returning Boyd’s writings to print and, beginning this year, will run an intensive workshop session for architecture students not unlike the Ozetecture Architecture Summer School in Sydney.

These programs all share a common DNA intimately tied to the Foundation’s mission statement. The open days are most representative: according to Tony Lee, executive director of the Foundation, typically 50 percent of the five hundred or so attendees at each open day are not associated with the design industry. Then there are the open houses themselves: otherwise inaccessible to the public, they are either modernist projects by Boyd and his contemporaries or new houses by some of Australia’s best architects. Here is an ongoing opportunity for architects and architecture to engage closely with the general public, and this assists the public in learning about the value of both.

There is another initiative the Foundation hopes to undertake, one that perhaps will even better respond to Boyd’s legacy. The reincarnation of the Small Homes Service as the New Homes Service will revive what I suggest was Boyd’s greatest achievement. The Small Homes Service published designs for small houses of one hundred to 120 square metres weekly in The Age from 1947 until the 1960s. The designs were available for members of the public to purchase for five pounds.3 Boyd accompanied each submission with articles offering comment on design and lifestyle ideas that resonated with his modernist values.

To be successful, the New Homes Service will have to overcome significant hurdles that didn’t exist in the 1950s. A wider array of lot sizes, established building stock in both inner-city and middle-suburban areas, stringent town-planning regulations and more expensive construction costs will all take their toll. However, careful targeting might ameliorate at least some of these complexities.

The larger lot sizes, greenfield sites and looser planning controls of the outer suburban growth areas are all conducive to the Service’s offerings, as is a population demographic usually more interested in volume-built housing than architectural design. This is the one area of Melbourne where architects have the least involvement and where the New Homes Service stands to have the greatest positive impact.

Perhaps in pre-emptive response to this issue, Lee will not be keeping the identities of architects anonymous, as was the practice in the Small Homes Service. Due to what Neil Clerehan, director of the Small Homes Service from 1954 to 1961, explains was the common social practice of frowning upon advertising within the profession, Boyd architecturally edited submitted projects to suit the Service’s needs and then released them for consumption without attribution to their original authors. In a poignant reflection of our contemporary attitudes towards advertising, the New Homes Service will use established architects with their own cultural capital to attract early interest. For now, Lee is remaining tight-lipped about who he has approached, though I wager that the architects whose work features in various Foundation initiatives will be first on the call sheet.

That there is a need for the New Homes Service highlights a challenge made all too clear when reading The Australian Ugliness today, fifty-three years after its publication. The social, regulatory and communications conditions in Australia may have changed significantly since the 1950s; however, our built environment is, as ever, riddled with poor-quality housing. Looking back at Boyd’s ideals, and considering the legacy he has left behind, it is unsettling to realize how many of the changes experienced by housing in the intervening decades have been negative. We may have planning regulations requiring consideration of neighbourhood character and amenity issues, but that has not stopped the bulk of housing becoming larger, more neglectful of the natural environment, less considerate of climate and less well designed.

This is not to suggest that architects are at fault – far from it. (If anything, it is the absence of architectural involvement in what has anecdotally been described as 95 percent or so of all new houses in Australia that is to blame.) Rather, it is the inconvenient truth that few architects are prepared to deal with the unglamorous, everyday kind of isolation experienced by the significant part of Melbourne’s population living in its outer suburbs. If our profession ever wants to alter this status quo, we need to recognize that there is a social dimension to the work we do, a shared duty of stewardship for the whole of the built environment.

The solution will not lie in architects designing more houses. Indeed, Boyd recognized the paradox of such a proposal, noting “there are not enough artists to cover the world’s architecture; but if there were it might be too many.”4 Instead, we need to step beyond our design roles, take on advocacy positions, invest ourselves in political and regulatory change and, most importantly, expose the general public to the benefits of good architecture.

If Boyd has taught us anything, it is that the conscientious architect is far more than a designer of expensive beach houses.

1. Until mid 2008, the Australian Institute of Architects was known as the Royal Australian Institute of Architects.

2. RAIA 1969 Gold Medal Citation, Architecture in Australia, December 1969.

3. Philip Goad and Julie Willis (eds), The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 632–634.

4. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness (Melbourne: F. W. Cheshire, 1960), 107.

Source

People

Published online: 19 Jun 2013

Words:

Warwick Mihaly

Images:

Robert Deutscher

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2013