The Architecture Critic

Rachel Hurst: senior lecturer at the School of Art, Architecture and Design, University of South Australia.

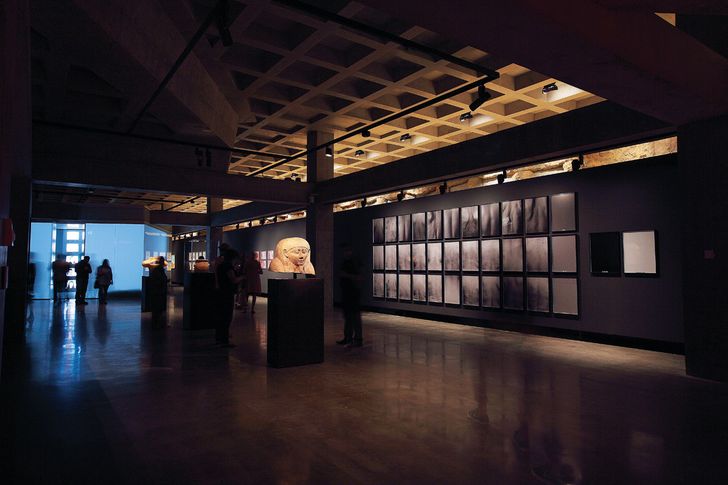

Ah Xian (Beijing, China), China China – Bust 82, 2004. Cast porcelain with hand-painted underglaze decoration. The portrait gallery can be seen in the background.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

David Walsh has failed miserably. In the substantial and subversive matt-black catalogue Monanisms produced for the recent opening of his Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Hobart, the eccentric collector and philanthropist Walsh declares that “Pissing off academics is fun”, and that part of the intention of this remarkable new private gallery designed by Fender Katsalidis Architects (FKA) is to challenge notions of how art is experienced. Despite this, MONA has ticked all the boxes in terms of standard museum features. In addition to over 6,000m2 of exhibition space, MONA houses a video-art cinema, bar, library, reading room and two artist-specific pavilions, as well as a museum shop and cafe. Buried three levels underground, the size of this subterranean complex is not immediately apparent, and it is only one part of Walsh’s extensive developments on this heritage site, the first vineyards in Tasmania. A visit to MONA can include “Eat”, “Drink” or “Sleep” packages in supporting facilities including winery, brewery, restaurant and the dramatic MONA pavilions (also designed by FKA).

But this is not about the sophisticated totality of Walsh’s vision for the Moorilla site. It is about the architectural container for his idiosyncratic collection and, like the collection, there is too much to digest in one visit, or cover in one article. (Digestive and bodily analogies are inevitable in this review, given Walsh’s clear interest in the visceral and scatological: if you are prudish stop reading now.) So despite its seductive magnetism, this will not be a discussion about the art, except in terms of its engagement with the architecture, nor will it be a descriptive journey through the building. You just have to go there for that. And every architect and architectural student and architectural aficionado in Australia should go there – soon.

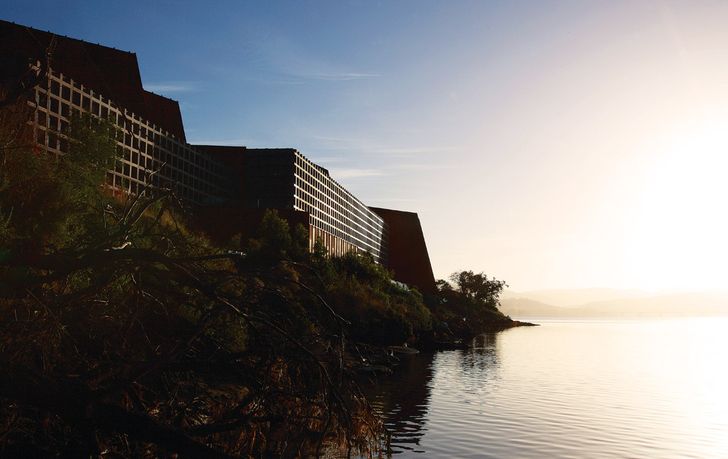

What will persuade you beyond the images accompanying this article? What do you need to know without detracting from the cinematic, suspenseful experience of this place first hand? Well, the best way to arrive is by ferry, as the journey there is far from the Stygian crossing one might anticipate on the way to a place so fascinated by death and sex. The sights pointed out along the way are contextual appetizers for what is to come – the sublime contraptions of the zinc refinery, the clutter of a cemetery between plump hills, and ancient striations of Indigenous stone caves at water’s edge.

MONA sits sentinel over the Derwent, its bulk echoing the riverbank topography. Immaculate coffered concrete spine walls and canted Corten plates shore up the site, with few openings penetrating this daunting artificial cliff save for a single Cyclops window overlooking the landing. Incorporated adeptly into the bunker-like language are two Roy Grounds buildings, the 1957 Courtyard House and 1958 Round House, which contain the entrance facilities and library respectively. The initial external impression of MONA is the least satisfying aspect of this otherwise exemplary project. Corten has become almost mandatory for contemporary art museums, and the pitch of the steel plates unwittingly recalls Wood Marsh’s ACCA. Even interpreting these tilted planes as abstracted naturalism, turning the building into landscape, FKA’s earlier, rectilinear, container-inspired use of the material, such as in the Melbourne Terrace or Hero Building, is more convincing. The waffle panels, too, though intelligent structurally and climatically, seem slightly forced externally. Internally, however, as slab and ceiling elements, they resonate with all the neoclassical authority and clarity of Edwards Madigan Torzillo and Partners’ National Gallery of Australia.

A winding Corten staircase traverses the central void.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

Circulation through MONA is, like so much of the place, unorthodox to the point of perverse. Entering at the cool intellectual patrician “head” of Grounds’ 1957 house, all platonic forms and elegant materials, one descends a downright funky steel and glass circular stair and lift well (kind of London Underground meets Archigram) into the bowels of the building. It is the first of a number of corporeal metaphors that the project suggests. As opposed to most contemporary art museums, the journey is away from the light, and increasingly textured and rough – almost primitive – as the massive quarrying through seventeen metres of Triassic sandstone is revealed. Pillowy drifts of shotcrete lining the descent shaft give way to the primal power of the rock and the engineering finesse at work in its exposure. The surface is scarified with circular saw cuts, pocked intermittently with rock anchors (like tiny display alcoves) and glistens with water and snowy salts leaching through the stone and collected in rubble-filled gutters in the floor. This is an archaeological abyss in keeping with Walsh’s original collection of prehistoric artefacts and early classical remains; a spectacular modern-day Petra in which to uncover new culturally significant objects. The theatricality of this first move into the galleries is – in the true sense of the word – awesome.

Deliberately labyrinthine, MONA is designed for visitors to get lost in, despite its essentially linear organization. I can’t shake the sense that Walsh lurks as the Minotaur at its heart, but that heart is actually occupied by a Corten stair of mythological valour. Fabricated in thirteen segments, this self-supporting construction is an alimentary canal of complexity. Though it appears to arbitrarily twist and leap through the structural grid, it connects the various gallery levels in a steely meander through the main penetrating volume of the building. The controlled bounce of the floor plates, echoing clang of footfalls and backlit handrail heighten its perilous, Piranesian atmosphere.

A walkway on level B1 peers through a void to the lower levels.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

The spatial narrative of shifting planar terrains recalls medieval streets that open and compress plastically – an organically evolved Greek town rather than an Acropolis to art – or, more pertinently, the cisterns and crypts beneath an absent temple. MONA positions itself repeatedly as a netherworld of viewing; a challenge to conventional perspectives on art and civic buildings, often through the simple act of reversal. It’s hard to actually see (and photograph) the building, for example: unlike most architecture of this degree of cultural import, it is not a pure object externally, but an assemblage of parts, portals and landscaped planes. It is all about the interior, and the interior of that interior. Looking up from the base level, the underbelly of the Grounds house is laid bare, its slab and footings coated to hold the surface, a compelling view one was never intended to see. (For another underside you are unlikely to have seen before, don’t miss the nearby LocusFocus by Gelitin).

Neither is MONA a traditional, controlled gallery environment in terms of ambient conditions. Noise and light spill from space to space, and rather than precisely temper each space climatically, MONA embraces the elemental qualities of water, light, air and smell, with an impressive balance between seamless mechanical servicing and raw sensory effect. Reinforcing the tactility of much of the art, there are clammy porous tunnels, dazzling crystalline pyramidal passages, smooth toxic rooms of lead and glass, and foetid laboratories for gastroenterological art. This is multi-sensory architecture of great competence, in terms of both concept and execution.

Erwin Wurm (Bruck an der Mur, Austria), Fat Car, 2006. Steel chassis and body; leather interior, with polystyrene and fibreglass.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

The empathy between collection and container extends beyond the haptic to critical criteria of scale and lighting. As Peter Timms noted in Meanjin, Walsh has gathered a true Wunderkammer of art. Its diverse curiosities – everything from painted Greco-Roman wooden coffin covers to gleaming porcelain turds to entire Mack trucks – demand equal spatial agility and specificity from the architects. Consummate proportioning and materializing characterize the range of galleries, from the more generic rooms for temporary exhibitions to the lofty Snake Hall of 1,620 Nolan drawings. Transitions between are fluidly handled: the dark, secret passage of 150 plaster vulvas invites close viewing (or licking, in the case of three fifteen-year-old boys). Pools of light provide wayfinding through the blackness, the uneven illumination imbuing the journey with a sense of de Chirico alterity. Jean Nouvel designed comparably and contentiously dark settings in the Museé du quai Branly, which oddly feels more pornographic and voyeuristic, in spite of its ethnographic, rather than provocative, content.

Andres Serrano (New York, USA), The Morgue (Blood Transfusion Resulting In Aids), 1992. Cibachrome photograph, edn 2/3.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

Perhaps it’s that while there is sensationalism in Walsh’s collection, there’s a different sensational quality to the architecture. The memorable experiences at MONA are undeniably physically and perceptually rich, but there is nothing in FKA’s resolution that is gimmicky, an attitude borne out by Katsalidis’s almost prosaic description of the principles at work – to solve things directly and keep the materiality very strong. The sensory rewards are the product of a refined but pragmatic architectural sensibility, so that in many places the architecture melts away despite its strength and muscularity, and the art, in all its wondrous, piss-taking iconoclasm, is foregrounded. The result is a serious conversation between architecture and art. If there is humour at MONA it is not whimsical, but a comedic laugh at taboos, and the recto verso of the commedia dell’arte, where the tragic and profound is only a breath away.

So sorry, David, you have failed. He declares that MONA is “going to mess with your head” and his collection may well do that, but the drama of this chthonic, subliminally disturbing place messes more with your body and heart. Not since visiting Canberra’s Australian Academy of Science (coincidentally another Grounds building) have I felt so convinced by an Australian building. Far from being pissed off, this academic came away exhilarated by one of the most exciting architectural experiences Australia has to offer.

The Curator

Jason Smith: director of Heide Museum of Modern Art.

Santiago Sierra (Madrid, Spain), Economical Study on the Skin of Caracans, Caracas, Venezuela, September, 2006, 2006. Set of thirty-five black and white photographs, edn 2/3.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

A review of the evolution of exhibition design and the role of the exhibition designer would reveal conceptual and practical approaches as divergent as the works of art exhibited. With some exhibitions, particularly blockbusters, there sometimes seems to be too heavy a reliance on the literally spectacular fitout of the space, and a sense that viewers increasingly expect exhibition design to condition or contribute to their experience of the art. Perhaps that expectation is not unreasonable: we all want space to inspire intellectual and emotional experience, but provided that – in the case of visual art – the space does not overwhelm the art or supersede it in quality.

The display of David Walsh’s collection of old and new art (at this point, within the framework of the museum’s opening exhibition, Monanism) succeeds quite brilliantly because it shows how design appears and simultaneously disappears. It reminds me of a text from a favourite Colin McCahon painting that is fixed in my memory: “this day a man is and tomorrow he appeareth not.” The restraint of the exhibition design strangely tempers the imposing scale, subterranean wonder and healthy ego of the architecture. This is no mean feat, given the curiosity the museum building itself has generated and the way in which a hunger to assess the architecture and the art can sideline evaluations of something as integral, and in this case, as understated, as the exhibition design.

The tunnel entrance leads visitors to the library and Round House.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

Restraint is the imperative that guided Adrian Spinks’s design concepts and resolutions: clearly he felt no need to challenge a purpose-built architecture with overtly conspicuous display furniture, contextually irrelevant supports or unnecessarily discrete environments. What Spinks has felt is the integrity and potency of particular works, and has understood the changeable but decision-making eye of Walsh – uber-curator/designer of the enterprise. Spinks has worked alongside, within (and hopefully at times without) Walsh’s prerogative to think and rethink the way in which he wants his collection displayed; that is, with anti-chronological juxtapositions and aesthetic connections or collisions.

Spinks’s modus operandi was to embrace the elegant but muscular architecture and its raw yet refined materiality to create displays subtle enough not to be noticed as design, but that helped to structure the viewer’s excursion though MONA. His design clearly asserts Walsh’s intention to question and reconstruct historical narratives; to unsettle aesthetic and taxonomic schemes; and to subvert conventions of display and interpretation.

Spinks’s eye has seen beyond obvious display solutions to envisage how the essence of an image, object or installation might be at once encapsulated and liberated for the viewer. For me this is no more evident than in the exceptionally beautiful and captivating vitrines displaying gleaming antique coins. In one we see installed a single gold coin, while in another we see a massed, abstract assembly of silver coins from different empires, regimes and periods. The coins in both “float” against a dense black ground, and are illuminated by a complex but, again, restrained exhibition and architectural lighting system that finely balances ambience and accentuation.

The zinc-clad Boltanski Pavilion is a secure, airconditioned bunker that contains Christian Boltanski’s The Life of C. B.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

Walsh’s antiquities collection is superb, but both he and Spinks knew that old coins would compete for attention against new works more challenging in scale and subject matter, hence the device of setting antiquities among twentieth- and twenty-first century works. For me, one of the intriguing outcomes of this strategy was an intensified feeling that the makers of the coins and antiquities were the great contemporary artists of their time.

The idea and format of the Wunderkammer could define MONA as an entity, and it is certainly elaborated by Spinks most adventurously in outdoor and indoor forms that are leitmotifs of Walsh’s intentions as well as prompts for the visitor. There is perverse fun and something strangely logical in a large-scale vitrine-cum-fish tank containing various antique fertility symbols, skulls and, of course, fish. Part Dr No, part temple or Eros, encountering this work in proximity (if memory serves) to Juan Davila’s The arse end of the world (1994), which shows the explorer Burke having his arse tongued by a kangaroo, confirms why the freedom of the private collection has so much appeal.

Waffle-like concrete panels clad the museum’s southern facade.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

There is democracy at work in the design of Monanism: there are no VIP works of art, and the fascinating “O” iPhone device is accumulating data for collector, curators and designers as they determine what and how to display next.

Spinks’s minimal approach to design responds perfectly to the content of works; to the scale of objects and the practicalities and potential imposed/proposed by architectural footprint and volumes. In contrast to generally vast open areas in which art installations and sculptural objects also operate as integral design devices, small votive objects and treasures are only to be glimpsed in intimate recesses, as if protected from the volatile forces of the outside world.

The ex-local

Katelin Butler: editor of Houses magazine.

Claire Morgan (Belfast, Ireland), Tracing Time, 2007.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

As an eighteen-year-old living in Tasmania, moving to the “mainland” could not happen soon enough. Now, ten years later, I look forward to going home. This is probably because I’ve grown up, but also perhaps because the cultural landscape of Tasmania has matured. The latest addition to Tasmania’s cultural scene is David Walsh’s Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), a museum that has established Hobart on the global art circuit.

This building is an example of how art and architecture can have an instant impact on the social and cultural reputation of a place; the so-called Bilbao Effect working its magic on Hobart. Andrew Bain of The Sydney Morning Herald wrote, “In a virtual blink, Hobart’s cultural landscape has been transformed, with art, wine, fine food and stylish accommodation becoming integral features of the city … If Hobart’s makeover has an origin, it’s the opening of MONA – the Museum of Old and New Art – in January.” MONA made the national press and international blogs before it opened. Like Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, MONA has been pivotal in the reinvention of Hobart as a cultural hub.

The Tourism Industry Council of Tasmania’s chief executive Luke Martin claims that MONA was “proving so popular it was underpinning the tourism industry in Tasmania.” However, this Bilbao Effect on Hobart has broader ramifications for Tasmania’s tourism industry. As reported in Hobart’s local paper, The Mercury, there is concern about how long people are staying in Tasmania. Rather than spending a week in the state and hiring a car to experience the beauty of the Tasmanian landscape, people are making short stays in Hobart only to visit the gallery. The next challenge for the state is how to entice holiday-makers to stay longer and to venture further afield. Tasmania is more than a one-hit wonder.

At ground level, a series of Corten walls shield roof terraces and green roofs.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

According to Martin, possibilities for packaging up MONA with visits to other galleries around Tasmania are being investigated. Although not directly related to these investigations, the 1891 Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery at Royal Park in Launceston is currently being restored to its original condition; there are also plans to extensively redevelop the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart. In addition to this new work, there are up to twenty other quality existing galleries in the state. So there is more to see than just MONA.

Gehry’s Guggenheim was constructed in the context of an extended campaign to improve the city of Bilbao and this is also true of Hobart. The architectural “wow factor” of the Guggenheim was the most famous component of the city’s facelift. So does Fender Katsalidis’s building have the same visual impact as the shimmering metal surfaces of Gehry’s building? Although large, the building is rather nondescript, sitting heavily on the edge of the Derwent River. So, no. The wow factor comes from the notoriety of Walsh, the unusual artworks and the context of the new building in a maturing city. The architecture, instead, has more depth of meaning and does exactly as it should: it supports the vision of the museum, essentially the vision of David Walsh. The dark, moody labyrinth of gallery spaces could metaphorically be likened to the mind of the eccentric professional gambler himself. Each artwork appears to be integrated into the dark materiality of the architecture – the interiors are far from light, bright and neutral, as might be seen in a more traditional gallery. The dim lighting and rough, rocky surfaces are a reminder that you are buried three levels underground.

View from Little Frying Pan Island across the Derwent to the Museum of Old and New Art.

Image: Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

The warped, mirrored surface attached to the original 1958 Roy Grounds cottage at the museum’s entry might be seen as the start of a journey of reflecting on oneself. Much of the art explores the human condition – there are uninhibited artistic descriptions of sex, death and even the digestion process, which includes fully formed faeces. Going to a gallery with such confronting artworks with your parents is an interesting experience. It’s almost like watching a sex scene in a movie with them. However, I was pleasantly surprised by my parents’ openness to the exhibitions. My father, who normally whisks through a gallery while my mother likes to take her time, happily spent almost five hours at MONA. This is because the gallery engages all your senses and you need to pause to understand the effect each artwork has on your body. This raises the question of who is actually visiting MONA – and it’s definitely not just the normal gallery-goers. People from all kinds of socioeconomic backgrounds are curious about what lies within the subterranean maze of MONA. Conservative minds are being opened, which is a good thing anywhere.

Call it the Bilbao Effect, but this phenomenon has been around for thousands of years – good public architecture forms the centrepiece of a city. Walsh himself abhors descriptions of the building as the Bilbao of the south, saying that Fender Katsalidis solved a problem, as opposed to the “architectural masturbation” of Gehry. This is probably true, but like the Guggenheim, MONA has initiated something very important for Tasmania and for Hobart in particular. Now the challenge is to build on David Walsh’s contribution to the cultural setting of Tasmania.

Credits

- Project

- The Museum of Old & New Art

- Architect

- Fender Katsalidis Architects

Australia

- Project Team

- Nonda Katsalidis, Robyn Bartley, Milena Beames, Roland Catalani, Man Ching Chan, Coen Chin, Karl Fender, Daniel Goldin, Kathie Hall, Ashley Hunnisett, Andromeda Hutchins, Nicolina Iuliano, Shem Kelder, Wayne King, John Lamb, Jessica Lee, Andrea Mancuso, James Pearce, Falk Peuser, Anne Sophie Poirier, Tom Robertson, Rochelle Rosenwax, Eve Sayer, Natalie Stone, Andrew Walter,

- Consultants

-

Builder

Hansen Yuncken

Building surveyor Philip Chun & Associates, Braddon Building Surveying

Civil engineers Johnstone McGee Gandy Engineers and Planners

Council Glenorchy City Council

Design consultant Tandem Design Studio

Fire engineering Lake Young & Associates

Landscape architect Oculus Landscape Architecture & Urban Design

Quantity surveyor Rider Levett Bucknall – Melbourne

Services engineer WSP Lincolne Scott

Structural engineering Felicetti

Superintendent Gallagher Jeffs Consulting

Technology consultant Aegres

- Site Details

-

Location

655 Main Road,

Berriedale,

Hobart,

Tas,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

Type Culture / arts, Exhibitions

- Client

-

Client name

Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart

Website mona.net.au

Source

Project

Published online: 30 Sep 2011

Words:

Rachel Hurst,

Katelin Butler,

Jason Smith

Images:

Courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art.

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2011