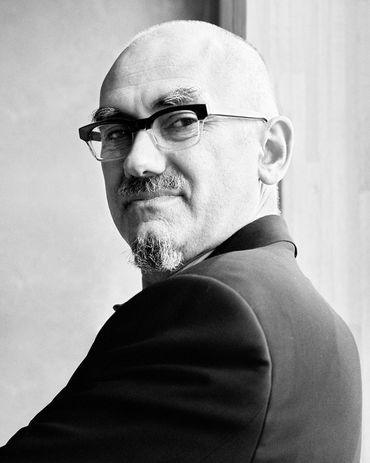

Peter Wilson, Bolles+Wilson.

Image: Thomas Rabsch

Recently I had an argument with a friend about Roxy Music. “I love Brian Eno’s designs! And music. What a great collaboration!” he said. “He had nothing to do with it!” I protested. “I was there! I know he hadn’t!” But a seed of doubt was planted. The thin guy with the long blonde hair who ironed his hair on the ironing-board in the house I shared with Bryan Ferry, was he Brian Eno? Was he there all along? I rushed to my record collection. No, I was right. No credits to Mr Eno in any Roxy Music album. Asked to write about Gold Medallist Peter Wilson, I began to rummage through my papers, fearful of false memories and the narratives that they fuel.

In 1974 Peter Wilson was awarded the Architectural Association (AA) School Diploma Prize, a prize I was awarded in 1971. After graduating, I ran an Interim Unit and worked in a Diploma Unit run by Bernard Tschumi. Peter, after graduating, ran an Interim Unit with Jenny Lowe and worked in a Diploma Unit with others before running his own. Jenny audited my “Drawing as a Thinking Tool” sessions. Did Peter? Probably not … but we shared space and have been on friendly if nodding terms since 1972. I certainly was observing and admiring his drawing practice. No one else thought so clearly through drawing.

In 1978 Peter was invited (by Peter Cook, I assume) to exhibit this drawing practice at Art Net. He called the exhibition Shades of Architecture, an apt title, as these drawings ghost between his past and his future practice. I have the invitation slip and the catalogue. In the catalogue Peter Cook aligns Peter Wilson with Walter Pichler, Raimond Abraham and (maybe, he writes) other exhibitors in A Space: A Thousand Words, an exhibition curated by Bernard Tschumi and RoseLee Goldberg at the RCA in 1975. Amongst these were Peter’s AA colleagues Jeanne Sillett, Jenny Lowe, Nigel Coates, Paul Shepherd, Will Alsop, the writer and the Zenghelises, Zoe and Elia. Perhaps there was a bit of a school of thought, or drawing, in this.

In Peter’s entry in A Space: A Thousand Words, there are three spaces: “A space for my mother; A space for myself; A space for an absent friend.” That seems important. In Shades of Architecture he has his Bird House (1976). In the attic, he writes: “A place for storing secrets, the past, human artifacts (sic), and a spare pair of wings.” I always had the feeling he was creating reserves of power. And here there is “A comfortable House for (Architectural Speculation) in the Metropolis” (1977). The section of this house merits study. On the rear ground floor, over a raised basement (how many of us lived in these buried places?), there is a very large window looking over the city, which – we are told, and the drawing suggests – lies in the valley below. Here the “projective eye” is invited to cast its assumptions over what it sees. Turn 180 degrees and we see something else entirely. Well, not entirely. A vertical shaft rises to the third floor above. Containing two angled mirrors, it projects into the room light from the outside and with that light, a view of the city below, slightly out of register with the one we see directly. Here we have a “receptive eye.” The former allows our preconceptions and our learning to range over the city. The latter forces us to observe what is actually there. Peter has stayed true to this observational model, mostly. Especially in his drawings and paintings of the exurbia of Eurolandschaft (Bolles+Wilson with photography by Christian Richters, Bolles+Wilson: Recent Buildings and Projects, Birkhauser Verlag, Berlin, 1997, 61), that ubiquitous terrain that most architects (and tourist boards) refuse to see.

In 1980, Peter published The Villa Auto. I don’t have this. My false (?) memory is of a flimsy document with atmospheric drawings of that laundry-iron-shaped apartment on two floors, linked by an external staircase off which was accessed the toilet. A fantasy constructed from memories of conversing in Münster in 2003 over a bottle of red that was splashed all over my white shirt and chinos by one of Peter’s gestures? My memory weakened by the trauma of walking back to my hotel mid-afternoon, confronting tut-tutting burghers.

Bridge Buildings and the Shipshape (1984), The Clandeboye Report (1985) and Informing the Object (1986) followed. Today I am struck by how “object” focused this drawing work is. In a completely unconscious parallel to Wood Marsh, Peter was – I think – building a platform for practice from the designing of urban furniture, setting himself up to furnish Europe with “new landscape measuring elements” (Lars Lerup, Mirko Zardini and Christian Richters, Bolles+Wilson: Nieuwe Luxor Theater, Rotterdam, Axel Menges edition, Stuttgart/London, 2003, 13). Space doesn’t get a mention. Perhaps it is ineffable. Western Objects Eastern Fields (1989) follows, with an interview with Alvin Boyarsky, in which Peter distances himself decisively from any lingering association with an AA “narrative architecture” school. For him, he declares, narrative is now sublimated. In this crux publication, Peter presents again the early projects mentioned above, some realized urban furnishings, the winning Münster Library design, a contemplation of the mythical figure of the ninja in a design for the 1988 Shinkenchiku “Comfort in the Metropolis” competition and a series of “masked,” vertically organized projects for Tokyo and elsewhere in Japan (Tokyo Opera, Cosmos Street – an HQ Office, and his Osaka Folie (sic)). Hard not to love these drawings. Hard not to mourn that in the main they were not realized as buildings. But easy to trace how the architectural ideas in them are present in the successive waves of built work that followed Münster Library. They manifest in the Akira Suzuki House, a miracle of compression and intimate immensity, as I observed in a loving if intemperate review for Architecture Australia (“Dark/Light,” vol 84 no 1, Jan/Feb 1995, 26–31). In the interview Peter displays an obsession with the writings of Virilio, then emerging as the theorist of anti-orthogonality, of the inclined plane, of the condition of endless movement. All these Bolles+Wilson projects have transcended the layer-cake sections that so often reveal the lack of plastic thinking behind sinuous facades, but counter to the restlessness there are these havens, docks of comfort.

There has always been a palpable aura of difference around Peter. Mike Gold (Peter Wilson (ed), Informing the Object, Architectural Association Publications, 1986, 7) identified this in part as: “Peter, at this time, had an incredible stammer. What others might regard as a problem, he typically turned to effect as part of his performance.” I think this delayed delivery of words was more than performative. As Peter spoke I thought you could see him choosing a word, rejecting it, reaching for a better one, finding a better phrase still. It was as if his two ways of seeing were also present in his verbal thinking. This was a delivery that eschewed the glib, the sparkling, the easy formulation, and it forced us, forces us still, into a slow thinking that parallels the making of architecture through drawing and redrawing. I think this reflection of real architectural thinking is why I prefer his spoken language, the interviews and off-the-cuff lectures, to his essays, which, more than his other works in any medium, play to a received notion of propriety.

Warehouse with rooftop waterscape, Münster, Germany, 2010.

Image: Markus Hauschild

Peter’s aura of difference arose also from his style of dressing. Even today there is something of the mid-twentieth-century gentleman about him. In A Space: A Thousand Words, Peter drew himself wearing an outfit only slightly exaggerating what he then sometimes wore. He is in tweed plus-fours gathered in at mid-calf. He is wearing brogues. He has a sleeveless, possibly Fair Isle, sweater and he is wearing a golfer’s cap. Famously, Peter has a moustache and thickly rimmed spectacles. If anything this is a P. G. Wodehouse character from the 1920s. This figure is drawn observing himself in the act of observing. Arrows shoot out from his eyes, triangulate and return. This in itself is a Heisenberg uncertainty principle moment; we are invited to wonder with Peter: “Am I seeing a wave? Am I seeing a particle?” If (as Yvonne Farrell of Grafton Architects mused to me in 2012) architecture is that moment when the intellectual becomes physical, Peter was already locating the core of that moment. And perhaps suggesting that we can only address it camouflaged in fancy dress, rather as the ninja (Peter Wilson et al, Western Objects Eastern Fields, Architectural Association, London, 1989, 11) “is the anti-figure to a samurai … a paid assassin who goes where it is impossible to get to …”

In case you are wondering, nowhere in these volumes does “I love a sunburnt country” arise. Perhaps these memories are locked away in those storerooms for memories. If so they are not let out. But a childhood stay in the annexe to the Imperial Hotel with meals in Frank Lloyd Wright’s building is treasured, and presented – a rare moment of eidetic recall. “When I was fourteen years old we stayed in the Frank Lloyd Wright hotel in Tokyo. To tell the truth, we stayed in the 1960s extension, but ate in the Frank Lloyd Wright dining room. My memory is of dark passages: the ceiling was painted blue with lights from beyond the cornices. It was like being in an Italian garden at dusk.” (Peter Wilson et al, Western Objects Eastern Fields, Architectural Association, London, 1989, 5.) Note that the allusion is vectored away from Australia to Europe, already calling …

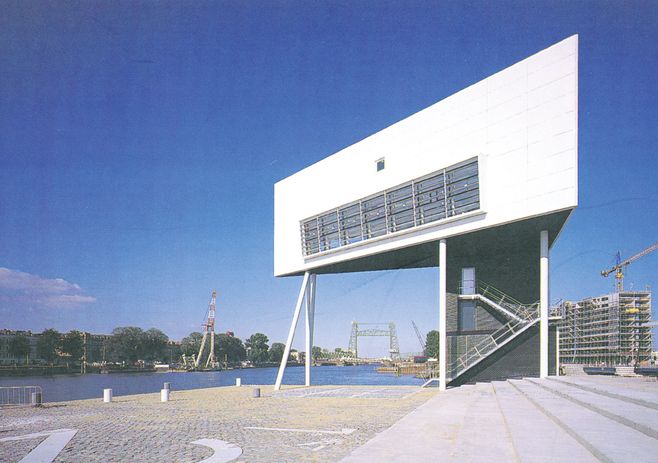

In 2003 a monograph on the Luxor Theatre in Rotterdam was published. A 1995 monograph featured the large-scale urban furniture of the Kop van Zuid that presaged the theatre. While I unabashedly love the work of Bolles+Wilson, and the Münster Library for me is the apogee of the entire AA school, this building exemplifies Peter’s engagement with the real landscape, the urban-scape of Europe. And it brings into play all the inventions of the 1989 monograph. A raunchy arm reaches out and captures some of that Dutch sky, so often sunken below sea level. Ninja shapes and masks whirl around the set piece of the auditorium, a giant piece of urban furniture.

Writing about Valerio Olgiati recently (2012), Peter says, “For Olgiati, as for Le Corbusier, discourse is marshalled by a sophisticated understanding and instrumentalising of mass media.” Peter is, as he admits in this writing, far less obsessive, less continental, avowedly and deliberately “Anglo-Saxon,” laconic, tongue-in-cheek. We have seen him assume this pose – wearing plus-fours, those symbols of amateur, sporting nonchalance – in A Space: A Thousand Words, his eyebrows arching slightly, wearing the shadow of a smile. I suspect he finds Olgiati to be “trying too hard.” But as with Olgiati and Le Corbusier, publications are vital to understanding the work of Bolles+Wilson. The work exists in a Plato’s Cave relationship to Peter’s drawings and watercolours, the buildings projected from these onto the walls of contingent reality: client, regulations, site, budget, contractor capabilities … This reference to Plato is no archaism. In a recent New Scientist (5 January 2013), Heisenberg’s wave/particle dilemma – the one that I find at the core of Peter’s wistful and gentle relationship to the world – is once again addressed. And the cave is called upon to explain the unnerving finding that we do indeed see what we set out to see, and a reality that must be neither wave nor particle eludes us. That I think is what gives the early books and the old drawings in them, and the new books and the watercolours in them, such power.

Hesitantly and can I say lovingly, they nudge an architecture into existence, an architecture that is so far from being dogmatic that it sits alongside the work of the Irish school (Grafton Architects, O’Donnell+Tuomey Architects) and looks uneasy in the presence of single-minded works based on Cartesian processes. Dublin, like Melbourne, is a post-colonial, provincial city. Both crucibles of creative musing on the hyperactivity of world cities like London. Perhaps after all, as Voznesensky wrote (1967), of the ways in which creativity launches from remote sites and crashes into metropolitan discourse, this is “the parabola” of the mental space from which this wonderful architecture has been generated and is constantly regenerated.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 22 Jul 2013

Words:

Leon van Schaik

Images:

Christian Richters,

Markus Hauschild

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2013