The May 2012 Australian Institute of Architects’ National Conference was harnessed around what some called a “loose construct,” or the theme of “experience.” Whatever exploratory license this theme afforded the speakers, many presentations seemed, nonetheless, to track two hot topics.

The first – noted sometimes with surprise – was landscape and the experiential influence of lived contexts, including specific biophysical environments. The second was a frank and sometimes subversive commitment to improved experiences for the socially disenfranchised or those more simply unnoticed and inadvertently marginalized. Such literally grounded activist projects have been emerging – or rather assertively re-emerging – from the canon of professional design projects for some time.

An ongoing design research project to improve the living conditions of Indigenous communities is being undertaken in the remote town of Warburton in Western Australia. It is led by AECOM, the University of Western Australia (UWA) and the Ngaanyatjarraku Shire Council. The project belongs in this difficult, protracted yet deeply rewarding field of activist projects.

The cultural, political and other dimensions of Australia’s failure to understand and substantively improve the lives of Indigenous peoples remains a matter that has to do with far more than additional funding, legislative amendment or well-marketed expressions of apology. These things are a start and are necessary, but it is how we commit to a future delivery that respects this start that is now the issue.

Student proposal: Jessica Dnell looks at modularity and form.

In 2010, AECOM and the UWA’s Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts led the establishment of The Sustainable Warburton Project as a remote, practice-based studio. It was founded on funding from the Ngaanyatjarraku Shire Council, with pro bono professional involvement from AECOM, staff at Monash University’s School of Geography and Environmental Science, and UWA’s design studio experiences with remote Indigenous communities. Initial site assessment was guided by experts in various disciplines, including environmental and climate science, hydrology, stormwater management and governance, and interrelated soil and ecological sciences.

The studio – initially open to senior architecture and landscape architecture students but feeling its way to wider possible collaborations – necessarily grapples with the multiple problems of finding structure for mutual learning opportunities of all stakeholders in an environment better suited in many ways to unstructured explorations. Academia and professional practice have parallel histories of collaborative engagement.

Their work with other communities has equally long but differently appreciated, partial and interrupted knowledge bases. Building relationships with Indigenous communities in remote areas poses a range of practical, logistical and cultural challenges. Any built form propositions obviously face the same challenges. The inseparability of the mutually metaphorical building of relationships and forms is, in many ways, the nub of the project’s research.

The studio practice, landscape experiences and cross-cultural exposures that make up the project endeavour to find and deliver expression of what is learnt and valued of each. That is: What do we value and deliver as the offering of design and designers in a given situation and time? What can we understand and value about a given landscape? And what do we really want and value about trying to understand someone else’s life-world in that place?

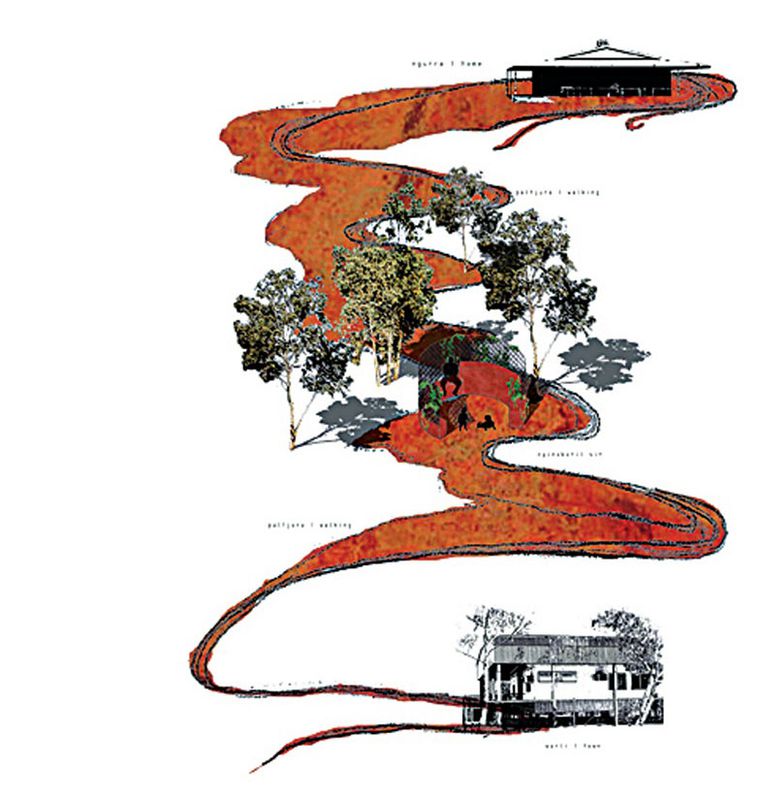

The first question generates responses proffering a ready range of technical and other expertise that would improve the spatial planning, construction and management of Warburton’s built environment. Important improvements addressing a range of local problems have been, and continue to be, developed. These include relocated energy sources and alternatives to the present diesel-fired station; rethinking of the sewerage ponds and their present and potential multiple uses; water harvesting and reuse, as well as flood mitigation at the other environmental extreme; increased vegetation for shade and/or produce; the suppression of dust, which can cause ill-health due to the presence of dried faeces from numerous well-loved dogs; incorporation of new and potentially integrated community education, training, recreation and trading facilities, along with employment opportunities and linkages from the main community to existing and enhanced tourist and council facilities; and reordering of circulation through the town for both car and pedestrian traffic, emphasizing predominant informal communal occupation and other habitation cycles.

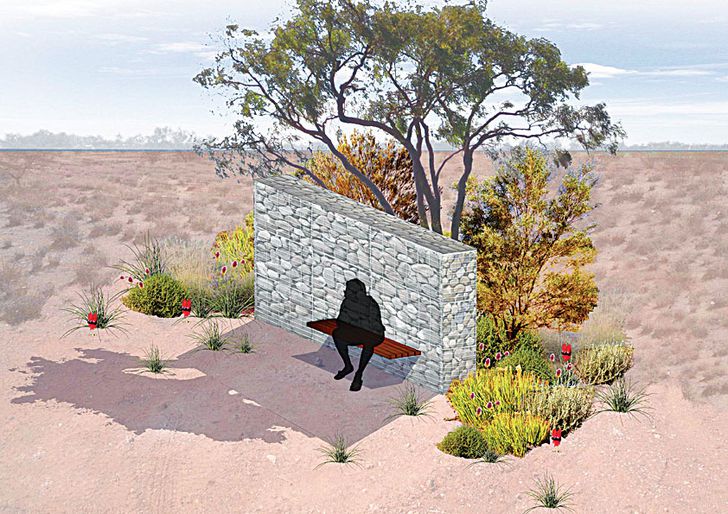

Student proposal: Jack Choi challenges the idea of space and use.

A masterplanning process that begins to draw together overlapping and flexible, optional threads for smaller staged improvement projects can provide the basis for funding and strategic grant applications. While such plans are a common part of urban settlement development (so much so that they can be overly prescriptive for designers responding to ongoing change in dynamic areas of expansion), models for Indigenous settlement and appropriate planned habitation patterns are a more recent and limited phenomena. Warburton’s legacy as a mission has provided an initial layout that has been variously and reactively modified over time in ad hoc and problematic ways.

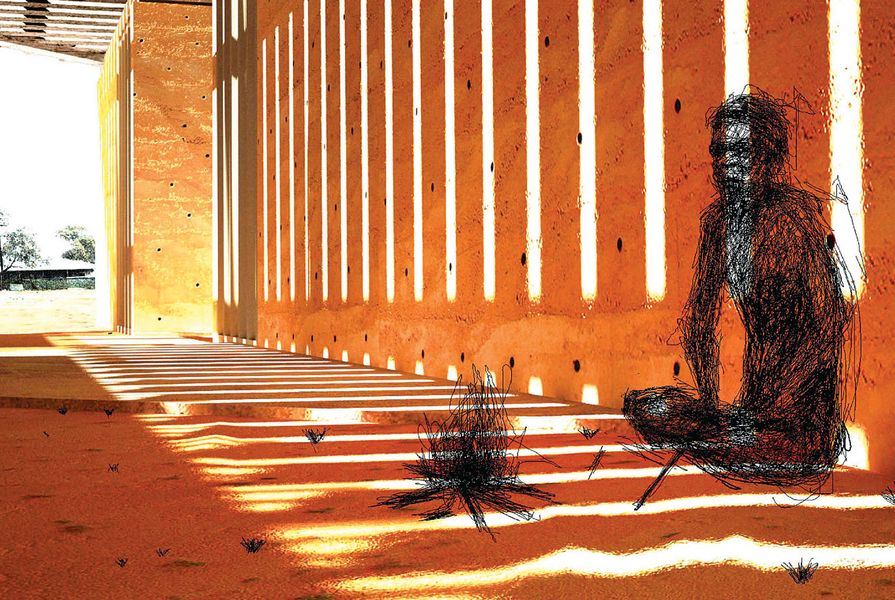

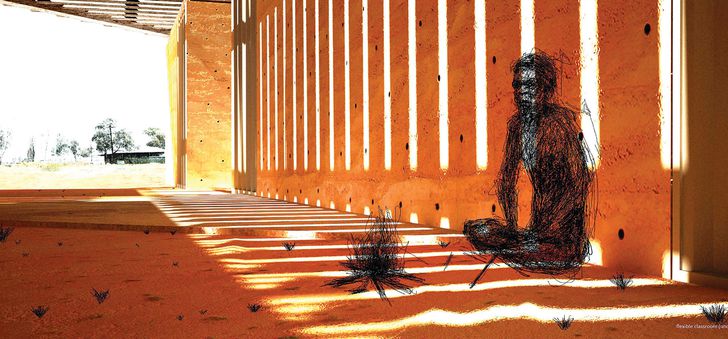

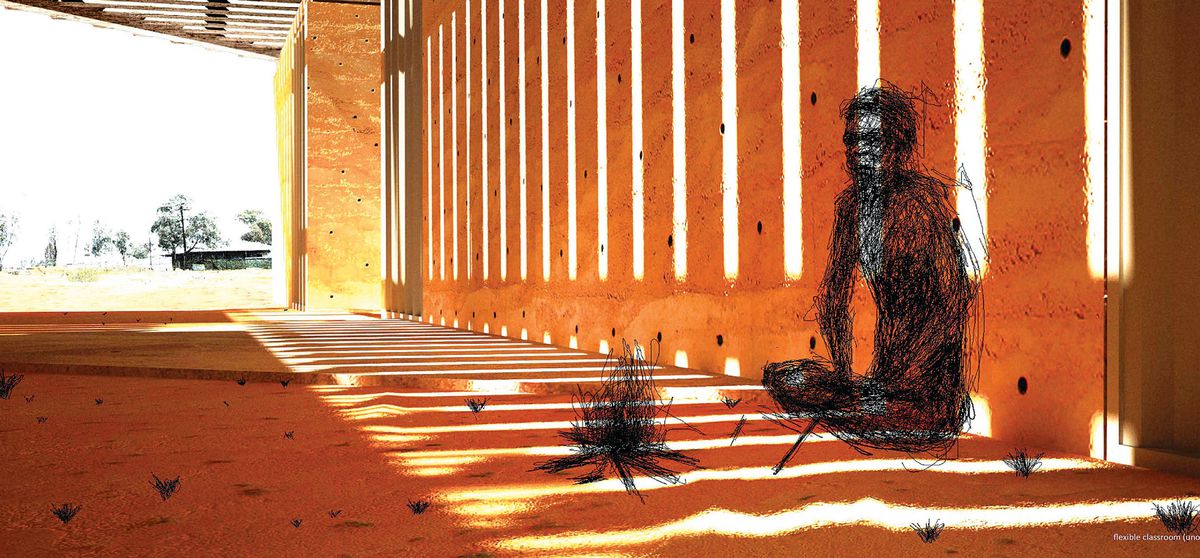

The second question of landscape value – certainly for landscape architects – crosses from initially easier claims based on practical application of certain formally acquired knowledges, training and expertise, into the more slippery realm of other knowledges and skills. Equally pragmatic and hard won, this experiential or aesthetic (knowledge through the senses) work of design thinking draws on historical, theoretical and other lessons to develop careful and self-conscious interpretations of observed environments, along with propositional alterations and enhancements that go beyond readily measurable efficiencies, but which are nonetheless demonstrable. As students looked to relocate or reinvent a variety of facilities, they also had to consider form, materiality and spatiality that would be responsive to an omnipresent wider – very wide! – surrounding landscape. If the first question holds answers of self-evident value, the answers to the second question might be thought of as further value-adding.

Student proposal: Jeremy Macmath promotes seed capture and revegetation.

It is with the last question, regarding the culture of a particular place, that design intervention finds a less easy justification and can less confidently claim specific disciplinary offerings. Yet this is the realm of the design imagination, central to mature design reflection and proposition and exactly what difficult situations need most.

Here the designer’s own life-world is called up and one must take stock of close and dearly held personal values. These can no longer be exercised in the abstract, at a remove, or via the pronouncement of universal principles, but must be examined in the light of a direct challenge to their immediate usefulness to others. The design imagination imagines other worlds: the worlds of those we try to help, as well as the future world we might create that is better and that, more importantly, understands “better” to be in terms that might not (yet) even be our own.

Of course all design and all projects do, and should, confront the designer in these ways. And this does not happen in a neatly procedural manner. Design research is, above all, research that makes these intermingled layers of confrontation explicit and helps us grow capacity and strength to deal generously with those confrontations. Design research in Warburton can be undertaken in and across all these layers, although its longer-term ambitions are clearly for that maturity that will build both relationships and an inspirational example of settlement for Indigenous communities.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 23 Jan 2013

Words:

Jo Russell-Clarke

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2012