Sometimes it can take time for the vision that belongs with a practice to emerge in a way that can be widely recognized or understood. In the case of Room 11 Architects, a practice based around Thomas Bailey, Megan Baynes, Nathan Crump, Aaron Roberts and James Wilson, operating with offices in both Hobart and Melbourne, there seems to have been a determination and distinctiveness present from the very beginning. Yet it is perhaps only now that the full extent of their vision can be appreciated. It is being realized in an especially striking way as part of the Glenorchy Art and Sculpture Park (GASP!) on the water’s edge at Elwick Bay.

Room 11 Architects (L–R): James Wilson, Thomas Bailey, Nathan Crump, Aaron Roberts and Megan Baynes.

There are few opportunities in Tasmania to work at this scale, and the Glenorchy City Council site also connects with David Walsh’s much-publicized MONA by Fender Katsalidis. The first stage of the project, a walkway that curves round the bay towards the point, has already reinvigorated a neglected and marginal location. Yet it is with the second stage of the development on the point itself – where the ribbon of the walkway is finally weighted down – that the project achieves its fullest impact. There the experience of the surrounding landscape is shaped in a direct and almost commanding fashion by long walls that extend along two cardinal axes. The command here issues less from the walls, however, than from the landscape itself.

Hobart is a windy place, and the point exposed, so that a key requirement is protection from the horizontal forces that blow across the site. The walls function as shelter, but since they partially obscure the western aspect, they also direct the view. Through the way they shelter and screen – a way that invokes a range of important architectural precedents even as it establishes its own – the walls make for a complexity in the structure of the space that would not otherwise have appeared.

The Glenorchy Art and Sculpture Park (GASP!) pavilion, Hobart.

Image: Benjamin Hosking

In spite of the widespread rhetoric that suggests otherwise, architects do not “make” places. Rather they respond to them, to the potential in which they consist (strange though this may sound), and which they also offer. The architectural vision that the work of Room 11 Architects articulates is a vision responsive in just this fashion – although, in addition, it is a vision that exhibits a remarkable clarity, simplicity and assurance.

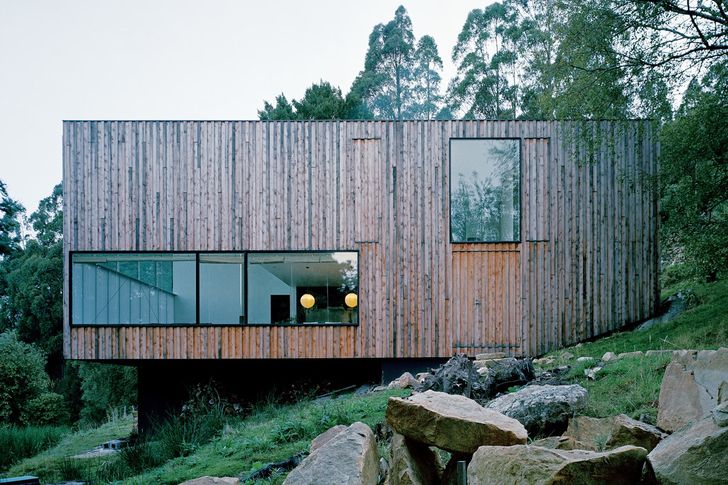

This vision is clearly present, not only in Glenorchy, where Bailey is the lead architect, but also in the house at Fern Tree designed by Bailey and his partner Megan Baynes (commonly known as the Little Big House). Building here, on the slopes of Mount Wellington, one might suppose the view would be everything and the aim to ensure none is missed. Yet from inside the house, one discovers that the lower half of the internal wall that looks in that direction is opaque, screening the main room from the road below, but also blocking the aspect beyond. The lower floor is not without views, but the screening of the lower wall creates a very specific bodily as well as visual orientation, while also intensifying the view available from the upper floor.

Little Big House.

Image: Benjamin Hosking

Again, the particular use of the wall as both screen and shelter (a fundamental architectural element made even more so by the deliberateness of its deployment) is one of the critical features of the design. The basic form of the building – an extended rectangle cantilevered out from a solid anchoring wall at the south-west end – echoes a key element of the form at Glenorchy. At Fern Tree, however, the building points longitudinally towards a view that is partially withheld, while in Glenorchy that view is opened up and it is the view on the long western side that is partially obstructed. Nevertheless, the obscuring use of the wall operates in a similar fashion – in both cases the wall serves to turn one back into another space (or spaces) opened up at right angles to the axis of the corridor. At Fern Tree, one is turned back into the building, with a glance up at the sky, then out to the garden. At Glenorchy, one is turned outwards to a stage that opens out to the landscape, even while still held in the embrace of the walls that shape the site.

Longley House: Natural materials tie the house to its surroundings.

Image: Benjamin Hosking

These spatial complexities, and the way they operate through a particular deployment of the wall, are evident in other Room 11 Architects projects. The wall is used in a way that intensifies its character as screen, as shelter, as anchor, as projection and also as enclosing bound. Perhaps nowhere is this latter use of the wall clearer than in the Room 11 Architects project at Longley, in which internal spaces are created that give the building an intensified interiority – through a darkened pantry, a sunken lounge, a sky-lit bathroom, a “courtyard” space cut into the building’s envelope.

Whether or not one wishes to talk about a “Tasmanian” architecture here, there can be no doubt that Room 11 Architects has a vision that is responsive to a set of topographic and climatic elements characteristic of the island. It is a powerful vision and one that will deserve close attention as it emerges further in Room 11 Architects’ future projects.

Source

People

Published online: 18 Sep 2013

Words:

Jeff Malpas

Images:

Benjamin Hosking

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2013