A tourist in one’s own city. Naomi Stead joins the curious public on the Historic Houses Trust’s Sydney Open, a day on which many buildings reveal their internal wonders.

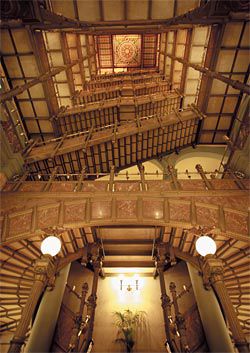

The sumptuous stairwell of the Société Générale Building, usually inaccessible to the public, was just one of the delights of this year’s Sydney Open. Image: Jody Pachniuk

Queues to get into Deutsche Bank Place, one of the most popular “open” buildings. Image: Jody Pachniuk

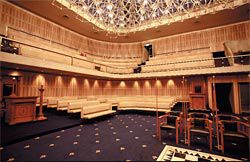

Sydney Masonic Centre and Civic Tower. Image: Jody Pachniuk

Participants descending the stair of the Société Générale Building. Image: Jody Pachniuk

Going up at the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Image: Jody Pachniuk

The stairwell at St Margarets Urban Village. Image: Jody Pachniuk

In the law of warfare, when it becomes clear that a given city can not be held against imminent invasion, its government may declare an “open city”. This declaration bears the expectation (or hope, since it has historically not always been respected) that the invading army, meeting no further resistance, will march in and occupy the city without destroying its architecture and landmarks, or attacking its civilian population. It is a mode of surrender, intended to preserve built fabric and human life, but it is also a powerful metaphor: in it the city becomes porous, without boundaries, something to be flowed through and filled to the brim. In a peaceful place such as Sydney, the warlike metaphor may seem inappropriate. But the notion of permeability, of the city as a diaphanous network of open pores, remains potent, and it well describes the event of Sydney Open.

Organized biennially by the Historic Houses Trust, Sydney Open is an architectural open day when a large number – this year 65 – of city buildings are accessible to the public.

Some of these are part of specially ticketed “focus tours”, which provide “in-depth access to private and fragile properties”, most often led by the architect or building owner. But the majority are buildings opened for this single day to anyone who holds a general admission ticket. Sydney Open began in 1997, following other successful events in London, New York and Toronto. It is now a fixture on the Sydney cultural calendar, and continues to grow in popularity and scope.

On the face of it, it is perhaps surprising that this event should be run by the Historic Houses Trust (HHT), given that most of the buildings featured are not houses, and many are also not “historic” in the sense of being old. In fact there is a fantastic collapsing of historical periods here – buildings that might usually be known as architectural “heritage” are displayed on the same plane as the most recent and cutting-edge constructions. And in this sense the event is entirely in keeping with the innovative and engaging public programmes of the HHT, an institution that contributes immeasurably to the cultural life of the city. In many ways the HHT leads the way in the display and dissemination of architectural ideas, both contemporary and historic, to a broad public audience in Sydney. In the Sydney Open guide book Peter Watts, director of the HHT, writes that the aim of the event is to “encourage a greater awareness of, and appreciation for, all forms and styles of architecture and design that contribute so much to our heritage and culture, encouraging us all… to develop a sense of ownership of our city.” Accordingly, the Trust reports that this year 5,000 people bought general-admission tickets, up from 3,706 at the last event two years ago. The most popular sites this year were Deutsche Bank Place, with a staggering 2,000 visitors, the Great Synagogue, and the Mint.

So there we all were on the day itself, Sunday 5 November, 2006. It was a grey, cold, and windy day in Sydney, with the city raked by fast-moving squally showers.

In spite of the weather, there was a celebratory atmosphere and a sense of camaraderie between participants, as we hiked around the city with our umbrellas and cameras, looking out for other people wearing the distinctive red admission sticker. Most also clutched a well-thumbed brochure, the map at the back marked up with each person’s individually plotted itinerary. There were many possible themes through which to organize the day’s path through the city; materiality, for instance, could have been one linking thread – examining the role that sandstone plays in the architectural life of the city, perhaps starting with the convict mason’s mark on each individual stone in the wall around Darlinghurst Gaol (now the National Art School). Or you could visit Sydney landmarks including White Bay Power Station, the underground remnants of the Tank Stream, and the Sydney Town Hall.

Or you could stick to contemporary, award-winning architecture. Whatever your taste and interest, people who wanted to nosy around the latest apartment design were equally as welcome as train-spotting historians, and both appeared to be outnumbered by regular, curious citizens of Sydney, hoping to see the city from new vantage points, to discover unexpected and secret spaces. Suddenly buildings which you might have walked past literally every day for years became more than just a facade: they are opened in every sense, taking on a depth of both space and experience.

Who would have thought, for instance, that there was such a sumptuous cast iron staircase in the Société Générale Building, which climbs acrobatically up a marble-faced lightwell towards an extraordinary stained glass ceiling. And while it has always been possible to see from the outside the sublime brutalist mass of the Sydney Masonic Centre and Civic Tower, who could have known that to be in this interior, with its highly figured off-form concrete and swooping heavy forms, would be like being among the turning cogs of a giant machine, the spaces themselves turning and meshing against one another.

Sydney Open also allows the populace an opportunity to see and understand those buildings that are “public” – institutions serving the public, working for the collective good – but which are not usually publicly accessible. Most people would hope never to see the inside of the cells and courtrooms at Darlinghurst courthouse, for instance, but the presence of this institution, the knowledge that it both symbolizes and facilitates the orderly processes of law, is a central part of living in a social democracy.

But aside from these lofty ideals, in visiting these buildings it is also the detail that is interesting, including the graffiti on the cell walls at the courthouse – “this cell has ears!”; “whatever you have done, remember God”. Likewise, the interest of Darlinghurst Fire Station is not just the lively brick and stone of Walter Liberty Vernon’s design, but the opportunity to see the way the firemen’s coats and boots are lined up, the whiteboard with notes about sporting teams, fundraising drives, and a phone number for “Deano”, the open-air boxing gym on a roof garden that would be the envy of any inner-city resident. There is a sense, throughout the fire station, of the many many hours spent here, training, keeping fit, and mostly simply waiting for the emergency which will send the trucks hurtling out onto Victoria street with sirens blaring. While the building itself is interesting, especially in the context of two other fire stations designed earlier by the same architect (at Pyrmont and Randwick), it is more compelling for the insight it gives about the working life of a professional fire-fighter.

It is not just as artefacts that the buildings suddenly become fascinating, it is as the intimate spaces of other people’s social and working lives.

By taking one day to specifically frame and re-present the city back to itself, Sydney Open makes architecture, in all its lived, built and temporal complexity, a legitimate object of appreciation in its own right.

It reveals the pleasure of becoming a tourist in your own city for a day.