Queensberry Street, north of Melbourne’s CBD, is on my preferred pedestrian route to and from the office. Along the way favourite moments include a Victorian shopfront of particular charm, glimpses into apartments above the footpath opposite Carlton Gardens, a better-than-front side elevation of a terrace and now, on the corner of Swanston Street, Jackson Clements Burrows’s (JCB) Upper House.

As a site, it marked the months for passers-by with daily instalments on construction: first, the delivery and speedy erection of the ten-storey podium’s concrete panels; then, the introduction of the recess at level eleven, which suggested the building’s parti was composed of more than one element; after that, the sprouting of “the cloud,” slightly set back from the floors below and subtly distinguished from the opacity of the podium by the introduction of colourback and clear glass cladding. What next? How high would it go? The cloud resolved itself into the five-storey cubic form it now is. Finally, the installation of the variably projecting balconies – plug-ons – added dynamism and depth to the envelope and achieved continuity between podium and cloud.

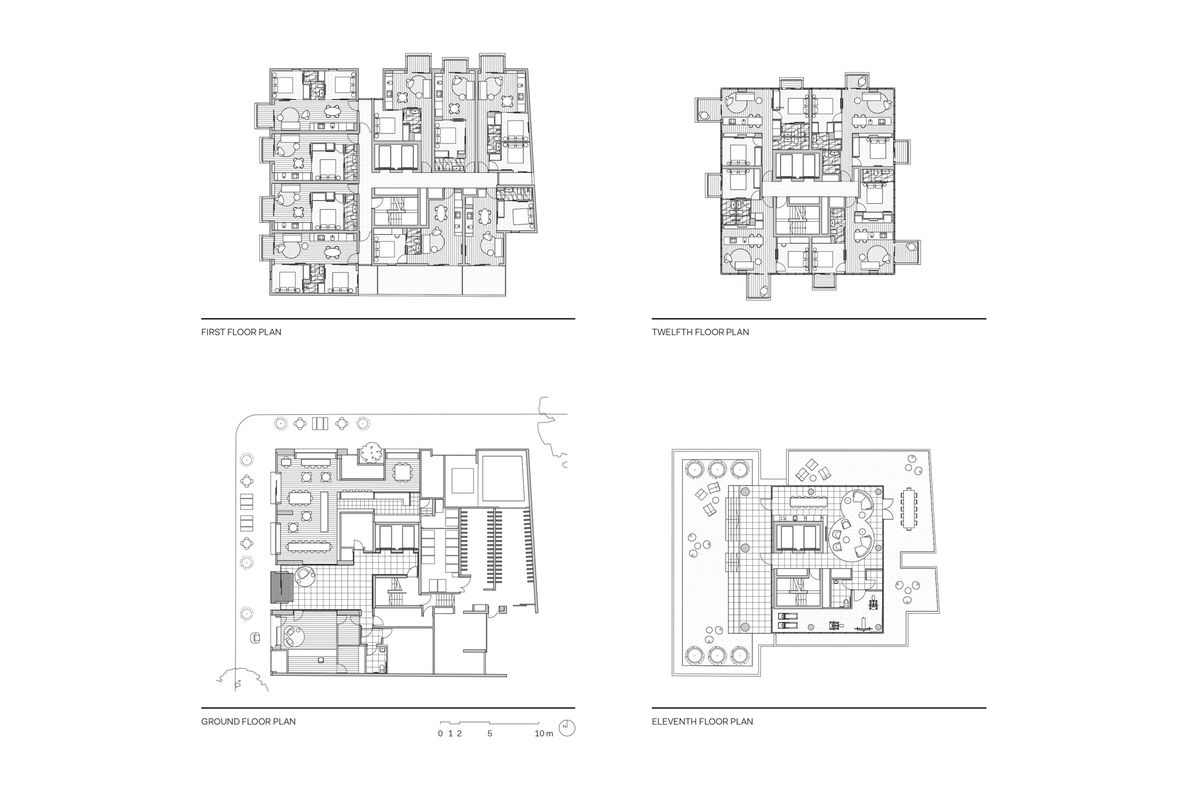

Upper House, located on the corner of Swanston and Queensberry Streets in Carlton, Melbourne, comprises an eleven-storey podium element beneath a five-storey “cloud” element.

In silhouette, the separation of the two is most apparent. An effective formal device, it also eased the way for additional floors during planning approval by incorporating a common area on the eleventh floor. The roughly anthropomorphic ratio between cloud and podium, coupled with the multi-eyed quality of the balcony projections, lends Upper House an anima that for me tips it into the category of kawaii, a Japanese term connoting cuteness. Its scale adds to this sensibility. Is it a tower, quite? At seventeen floors, probably, but relative to some of its neighbours, such as the ARM beast to the south-west,1 and within the context of Melbourne’s current predilection towards the 100-storey-plus, it feels smaller, somehow more endearing. But if a tower is a question of proportion – taller than wider, evidently vertical – then yes, a tower it is.

It certainly is petite. From a site area of 552 square metres, the yield is 110 apartments: 1992 dwellings per hectare. Skilful planning extracts plenty of amenity via the compact arrangement of modest floor areas. Which raises pertinent questions about size: Does it matter? How small is too small? Is there a place for standards prescribing minimum apartment sizes in our current regulatory environment? Upper House apartments – 41–43 square metres for a one-bedroom, 56–64 square metres for a two-bedroom – have considerably smaller floor areas than the suggested minimums recently flagged by the Office of the Victorian Government Architect (50 square metres for a one-bedroom) or as legislated in the New South Wales State Environmental Planning Policy 65 (50 and 70 square metres for one- and two-bedroom apartments respectively). Yet despite this, key benchmarks for amenity – natural ventilation and light, visual aspect – are well met in the apartments and the common areas. The risk with prescriptions on floor area is that they reinforce an Australian preoccupation with quantity over quality, which accounts for the flabbiness we often see in new house plans from the “if in doubt, add more” school of design.

Instead, at Upper House we have precision and clarity, precious space allocated in ways that target the most opportunity for living well. Thankfully this means questioning the addition of a second bathroom when one will suffice, and integrating a dining table as an extension to the kitchen bench rather than delivering a too meagre dining area just to play the marketing game.

Though the floor areas are smaller than the standards recently recommended by the OVGA, the compact apartments have plentiful access to natural light and ventilation, and visual aspect.

Other “tests” Upper House might not pass include a bedroom located off a living area. Yet here, the arrangement works. Used in the majority of the one-bedroom apartments and the two-bedroom in the podium’s north-east corner, the sliding door detail – wide, full height and with recessed track – divides sleeping and living to substantially open the aspect from the bed to the world outside. In the podium, Upper House has nine rather than the recommended eight dwellings per lobby, and not all apartments have north-facing living areas. But they do all have high levels of natural light and only one per podium floor is solely south-facing, obtaining daylight rather than direct sunlight. I stress that it is good design that makes petite at Upper House desirable. In the wrong hands, petite could and does go horribly wrong. But still it is worth asking: Is the purpose of minimum floor areas to hinder innovation or limit the damage of the dreadful? As the primary mechanism for eliciting good design, they are not a panacea.

What adds considerably to the sense of spaciousness is the flow between primary and secondary spaces, reinforced by the continuous ceilings. Remarkably, the battle that typically plays out in multistorey apartments between building services and volume – the scar of which is the plasterboard bulkhead – has been won. There are none. The lack of bulkheads may seem like a small point, but in the context of developer-driven housing it is a major achievement. It signals effective design management, central to the architect’s role, and the constant vigilance to not acquiesce to expedient solutions and to find a robust and appropriate design intent relative to the project parameters. If the profession wishes to claim leadership in high-density housing delivery – the bulk of current construction – then it needs to embrace this role. Only then can architects do more than put lipstick on pigs and play a formative role in the making of our cities. With this project, JCB shows how clarity of intent enables design delivery within the time and cost limits of a commercially successful project. Full credit, too, to developer Piccolo for standing by the choices made by its architects, evident in the resolution of the overall concept.

The Observatory, a communal space on level eleven, is located at the break between the two volumes.

But back to the street. With the ground floor pending occupation, the more rewarding experience of Upper House is, appropriately, gained by looking up. The reflective underbelly of the cloud presents, downside up, The Observatory – a communal space atop the podium, visually greened with artificial grass and complete with recliners, barbecue, gym and lounge. What a clever way to bring the life up there down here to the street, views of tops of heads included. Situated within the visual break of the building’s parti, a prime spot you’d expect to be reserved for the penthouse, the common heart is explicitly expressed in the resultant urban form and evident from the street. It marks a shift from the roof garden as the topping on a multi-residential project. A post-occupancy study of how it is managed and the extent to which residents can practise a more collective pattern of outdoor recreation here will be interesting. My one “if only” for Upper House is that the sole living tree, in the bottom of the north crevice of the podium, could have been part of a forest on the otherwise quarantined landscape of The Observatory.

Like many Melbourne towers, Upper House has a central core, a mix of one- and two-bedroom single-level apartments and no car parking. What distinguishes it is the level of amenity – the experience of space – achieved from modest areas, and its deployment of a centrally organized, four-faced typology normally reserved for a freestanding rather than a corner siting, within a pattern of infill to street edge. This results in apartments with a variety of aspects and no real “back.” The fact that we can see it in the round is part of its delightful objectification. Even with future neighbours hard up against the east and south faces of the podium, the cloud will, by virtue of its setback, remain a free-floating element. But most remarkable is the relationship to the city that Upper House enables. Within the apartments, compact interior space is visually extended over rooftops and out to the wide horizon. The balcony as suspended room surrounds the occupant and combines haptic intimacy with the visual thrill of the city as spectacle. With so much out there, so little is required in here to live densely, and live well.

1. ARM’s Swanston Square, known as the Portrait Tower, is a thirty-one-storey residential tower containing 530 apartments, located at the corner of Swanston and Victoria Streets.

Upper House by Jackson Clements Burrows received the Best Overend Award for Residential Architecture – Multiple Housing in the 2015 Victorian Architecture Awards.

Credits

- Project

- Upper House

- Architect

- Jackson Clements Burrows Architects

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Tim Jackson, Jon Clements, Graham Burrows, Chris Manderson (project architect), Blair Smith, Simon Topliss,

- Consultants

-

Acoustic engineer

Acoustic Logic Consultancy

Builder Hamilton Marino

Building surveyor Reddo

Fire engineer Thomas Nicolas

Services engineer ALA Consulting Engineers

Structural engineer Rincovitch Consultants

- Site Details

-

Site type

Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2014

Category Residential

Type Apartments

Source

Project

Published online: 28 Jul 2015

Words:

Kerstin Thompson

Images:

John Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2015