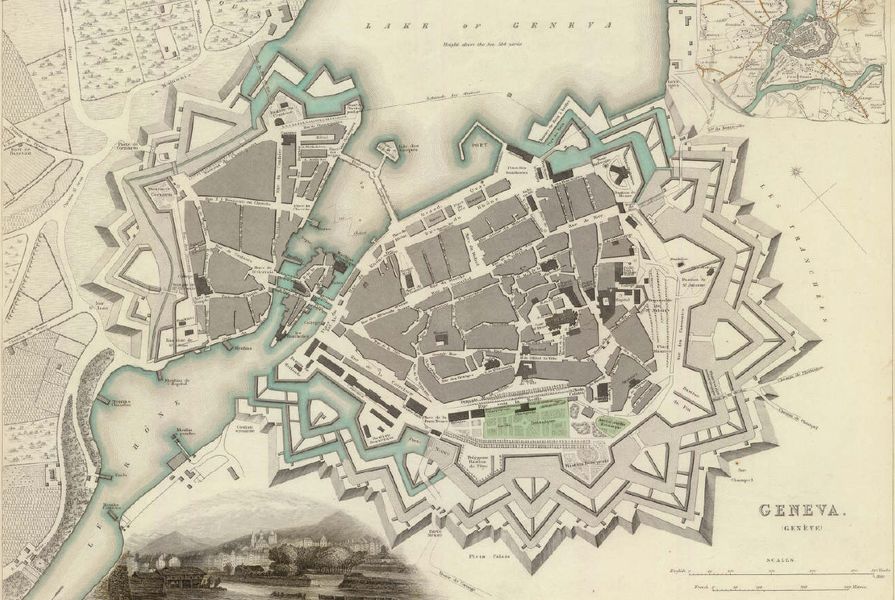

Paul Virilio’s view on the relationship between war and the city came to mind as, over the past month, 100 people died in a terrorist attack in Ankara, Turkey, 40 were killed by suicide bombings in Beirut and then 129 were murdered in coordinated attacks in Paris on the 13th of November. A French urbanist and cultural theorist, Virilio experienced the horrors of WWII as a child and, as an adult, saliently predicted the Gulf War, the fall of the Soviet Union and the September 11 attacks. His books are read in military academies and they’ve also been popular with architects. In Speed and Politics (1977), Virilio argues that the form of the city is determined by the weapons of war. The city, he declares “is constitutive of the form of conflict called WAR, just as war is itself constitutive of the political form called the CITY.”1 Virilio cites as evidence historic examples such as the obsolescence of the walled city once the cannon could surpass its battlements. He also proposes that the form of the city is as much concerned with threats from within as it is with the defense of its citizens from enemies beyond.

Virilio’s writing is gripping, but his take on the city is reductive, paranoid and apocalyptic. Cities have, arguably, evolved in response to multiple social, political and technological forces. The history of the city is equally a history of manufacturing, a response to advances in medicine and hygiene, and an effect of new forms of transportation that change patterns of trade and time itself. Without, say, the elevator and the pump, we’d not have high-rise towers and cities of the density we do today. Pleasure, too, is as much a source of the vitality of cities as is the exercise of control. Despite these reservations, Virilio’s understanding of the contemporary urban condition is useful and possibly gives us insights into how warring states and terrorists both view cities.

Virilio believes that from the beginning of the nineties “communications weapons” have superseded weapons of destruction, such as bombs, and weapons of defense, such as armour, tanks and fortified buildings. He claims that war, including terrorist attacks, now takes place with a minimum of actors, who may be robots, commanding maximum media coverage. He calls this the miniaturization of destructive power.2 Virilio also proposes that war has been transferred from the realm of the actual, to the virtual and mediated. He predicts the imminent dematerialization of architecture and the city – a situation wherein public space has been usurped by the televised media, the street abandoned for the domestic display terminal. While it is true that drones are operating in the so-called “war on terror,” it is not true that war has gone entirely virtual. War today is both virtual and real.

The attacks in Paris involve a small number of assailants and though many died, in comparison with ISIS assaults in Syria and Egypt, the number of victims is relatively few. Unlike in ISIS’s field of operations in Syria and Iraq, the intention was not to overtake, subdue or destroy the city. It was a symbolic act that gained impact thanks to the global propinquity of contemporary media coverage, through both formal and informal channels. The destruction also gained power from the physical sites in which the massacres took place: the open boulevards and a café-concert theatre built in 1864 during the period of Baron Haussmann’s interventions. The targets of the September 11 attacks, the Twin Towers and the Pentagon, were so clear in their symbolism, but the Bataclan?

If cities respond to the evolving technologies of war, then what we have witnessed over the past decade or two is a shift, not in weaponry per se, but of the “kind of war” being waged. After September 11, the US administration used terms such as “global war on terrorism” and tended to merge terrorism and rogue states into an “undifferentiated terrorist threat.” War expanded to mean not just a military operation but also intelligence, diplomacy, the surveillance of citizens, police work and communications strategies. Traditional wars begin and end, whereas the West’s “war on terror” and ISIS’s quest to eradicate what it has described as the world’s “state of ignorance” have no such definition. Virilio calls it “undifferentiated terrorism.” The entire globe has been brought into war’s violent embrace. France and her allies in the West are the target, but generalized such that any site in Paris can stand in for the nation. Indeed, Harlem Désir, the Secretary of State for European Affairs in the French parliament, has claimed: “France was attacked, but all of Europe was hit.”

Past terrorist attacks have largely concentrated on a recognizable range of sites – airports, public transport and stations, the corporate headquarters of multinationals, embassies and government buildings, hotels frequented by western tourists. These sites are either symbolic of the state or places where large numbers of people are gathered. Architects have been engaged in designing solutions for these programs that fortify them against the new mediated and miniaturized forms of war. A whole panoply of material and dematerialized technologies has been invented, from foyers that have no concealed nooks or crannies, to sculptural bollards and back-up energy generation. The Paris terrorist attacks invite this level of fortification to the entire city, for the attackers appear less interested in the number of victims or who those victims are, as they are in expanding the potential of victimhood across the city, to all its denizens.

So what of the city? What will it become in response to dispersed and continuous war? Virilio’s diagnosis is that the state’s response will be one of creating policies for the orchestration and management of fear (rather than its alleviation). If he is correct, then an architecture of fear in the form of defensive public and cultural spaces is coming, if not already here. The French places attacked on November 13 were spaces of inclusivity where there was freedom of circulation and association. These are the necessary principles of public space. If the ambition of all terrorists is to inflict terror as a way to gain power, then this ambition is firmly realized if public space and the freedom of all citizens to use it is further eroded, as it already has been in the virtual realm.

1. Paul Virilio, ‘Foreword’, Desert Screen: War at the Speed of Light, trans. Michael Degener, London: Continuum, (1991) 2002, p. 5.

2. Paul Virilio, A Landscape of Events, trans. Julie Rose, Cambridge: MIT Press, (1996) 2000, p. 21.