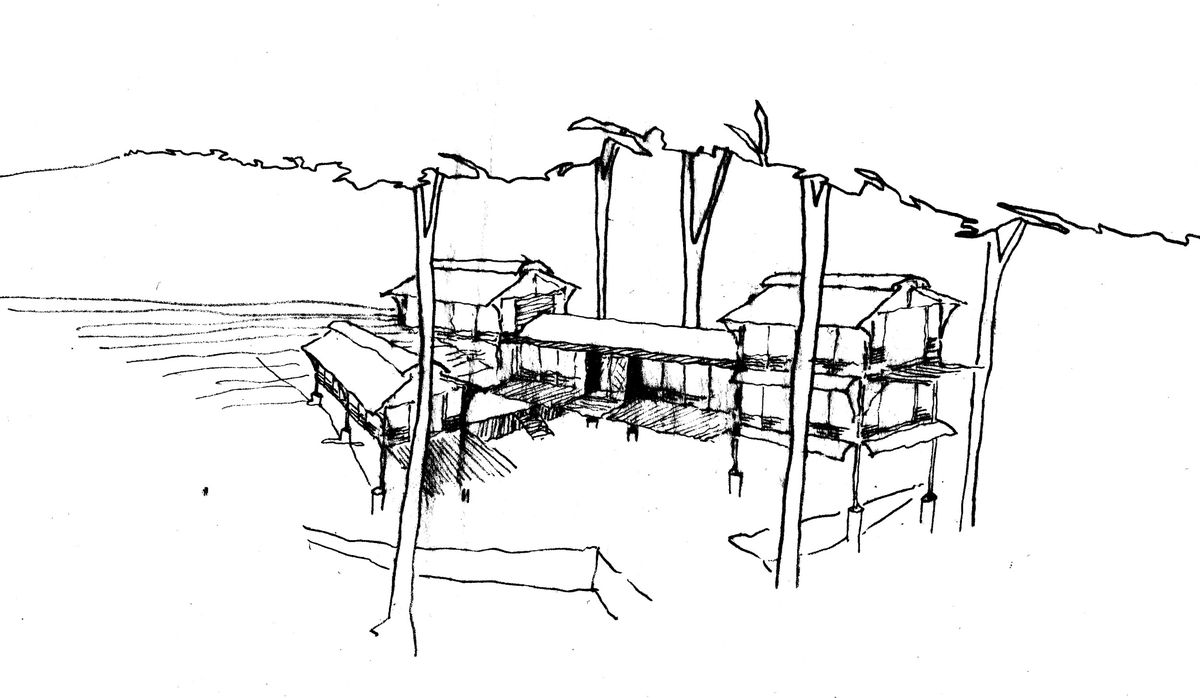

Twenty-seven years ago architect Peter Stutchbury and landscape architect Phoebe Pape began their West Head House in Clareville Beach, Sydney. Overlooking Pittwater, the site they chose is steep and from it rise the great, smooth trunks of spotted gums that form the canopy above. When it rains, water courses over rocky outcrops and soaks any flat ground. It is a typical western shore landscape , beautiful to walk through but not easy to inhabit. Its nature required a skilled response.

Peter was inspired by the architecture of the landscape-based cultures of Australia and the Pacific rim. He had not long returned from the highlands of New Guinea, where he lived for two years and practised architecture. He made meticulous measured drawings of important long houses, which are a valuable record. He had already built several accurate, pared-back houses in New South Wales.

This house is essentially two pairs of linked pavilions. Sleeping and bathing are placed along the contour at the top (east end) of the site behind a veil of casuarinas that filter the sun, while the winter room and summer room are on the southern edge of the site, reaching down the slope and with a long, open side to the north.

Rooms are accessed externally via timber decks, prioritizing experience of site.

Image: Michael Nicholson

The house is a hardwood post-and-beam construction, with tall tallowwood corner posts pinned into small concrete footings or directly to exposed rock. The entire frame is stop arrised. A fin plate system in galvanized steel makes all the structural connections, fully housed, on the centre line of the timbers.

Thin steel roof portals with fine stiffening gussets lean out from the frame at sill level to support the sheltering and sharp-edged roofs. Peter explored this articulation in the Hilltop, Israel and Gilbert Houses at the time, and recently in Cliff Face House, a collaboration between my own practice Fergus Scott Architects and Peter Stutchbury Architecture.

West Head House was built to the highest quality; the care taken more important than completion. The expense in this building is in human effort – far preferable to high-energy material. Peter placed an advertisement for a craftsman builder and so Jeffrey Broadfield imbued the construction with his unique talent.

After a journey through the site, from the bottom of the hill, up weathered timber stairs and over sandstone benches, the house is reached across a hand-carved stone platform. It seems to pivot around an old ironbark tree growing through the eaves at the entry. Shoes come off under the clear roof of a stone anteroom and a cedar door rolls back smoothly on weathered brass hardware.

The kitchen sits on the bridge running from the winter room to the summer room tower.

Image: Michael Nicholson

The space is serene, offering the warmth of a blue gum floor and flooded gum lining, and the smell of the fireplace. This is the winter room, with a low scale and a loft overhead. An old oak table, family photos, artworks and handmade gifts received over the years are respectfully placed above the mantelpiece.

As the site drops away, the plywood kitchen rests on the bridge that links the winter room with the summer room tower. Windows lift up to the northern light and Pittwater view, the breeze moves across the room and one is standing at canopy level among the trees.

Peter’s first design studio was under the summer room – a double-height space opened at the corner to the sun, with glowing polycarbonate walls overhead. As a recent graduate I worked there with Martina Shelley and Jonathan Temple. There was no computer and the fax machine never functioned well because it was full of sugar ants, but we filled the plan chest with drawings. The studio was about three metres off the ground and there was no connection to the cliff behind, except the narrow plank that our visitors had to walk.

Architects often run out of funds when they build for themselves with such care and it took some time to complete the skin of the building, but the openness was also intentional. Each room was externally accessed from timber decks. The bath pavilion was open to the climate. Laundry, storage and dishwashing were outside; there was no oven, microwave, dryer, dishwasher or vacuum cleaner. The usual layers of suburban life were pared back to the essential. Constant physical comfort was eschewed for experience of site. After a few cold winters, Peter’s father Ern Stutchbury and Rick Leplastrier helped install the slow combustion fireplace. Soon after, Phoebe gave birth to her and Peter’s first child, Bronte, at home.

Their house evolved with their family. There was a new layer of resourcefulness and play. Suddenly the open timber platforms up in the trees all needed balustrades. Peter designed them in galvanized steel water pipe and fishing net. A salvaged pink claw-foot bath became the centrepiece of the bath pavilion.

As the kids grew, the studio got a bouncy plate-steel internal stair and became Bronte’s room. Daughter Clea got the treetop loft with the ringtail possum nest, and son Noah got a wedge-shaped room with inbuilt bunks among the banana trees. My kids loved the house – it was an adventure playground.

As children grew, spaces such as the original studio under the summer room were transformed.

Image: Michael Nicholson

West Head House is an embodiment of an attitude towards site, and an exploration in living minimally with careful use of resources and with awareness of landscape. But it is also an example of how a dwelling can develop organically with a family, accruing its history. We learn that a house can’t be static if it nurtures life. This house became treasured by a young family and will be missed.

I have just visited Peter at his new home, tucked in behind red-brick flats near a busy beach car park. It is a Serengeti tent, over a hardwood deck in a garden. There are new coast banksias, fruit trees and a vegie patch. I am greeted by his partner, architect Fernanda Cabral, who designed the home with Noah.

The camp kitchen is in the annexe but Peter cooks outside in the clear night. His three children join us with some friends. They all have a keen interest in environment and architecture. We sit on the edge of shaped deck boards and talk until late. The surf rumbles in the distance, there is a wide night sky above. There is vitality in this set-up and in making a new place. Peter continues to shape his surroundings, true to his principles.

This review is part of the Houses Revisited series.

Credits

- Project

- West Head House

- Architect

- Peter Stutchbury Architecture

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Consultants

-

Engineer

Eva Tihanyi

Landscape architect Phoebe Pape

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Coastal

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 19 Mar 2015

Words:

Fergus Scott

Images:

Michael Nicholson

Issue

Houses, December 2014