“In this sense, ‘architecture’ – the totality of structures, systems, ideas, practices that are bound up with buildings designed and built by architects – is an ideology. It takes its place beside law, religion, and the rest, as the mystification of material practice.”1

In reviewing another thoughtfully wrought building by architects of demonstrated professional stature and commitment (in this case Six Degrees Architects), I would like to ask the following: What does this building – this work of commitment, professionalism and obvious competence – ask of us? What does it offer us at the level of professional discussion? I am particularly interested here in putting out some thoughts that we might usefully bring to the work and more especially to the design processes of its making. As Roland Barthes has written (quoted by Manfredo Tafuri), “the duty of criticism is to start from the work, not in order to make its meaning clearer – nothing is clearer than the work itself – but to generate new meanings from it, to multiply its metaphors, to satisfy somehow, the enquiry that the work of art incessantly proposes on the sense of its construction.”2 And in works of architecture too we can look for this enquiry in the sense of their construction.

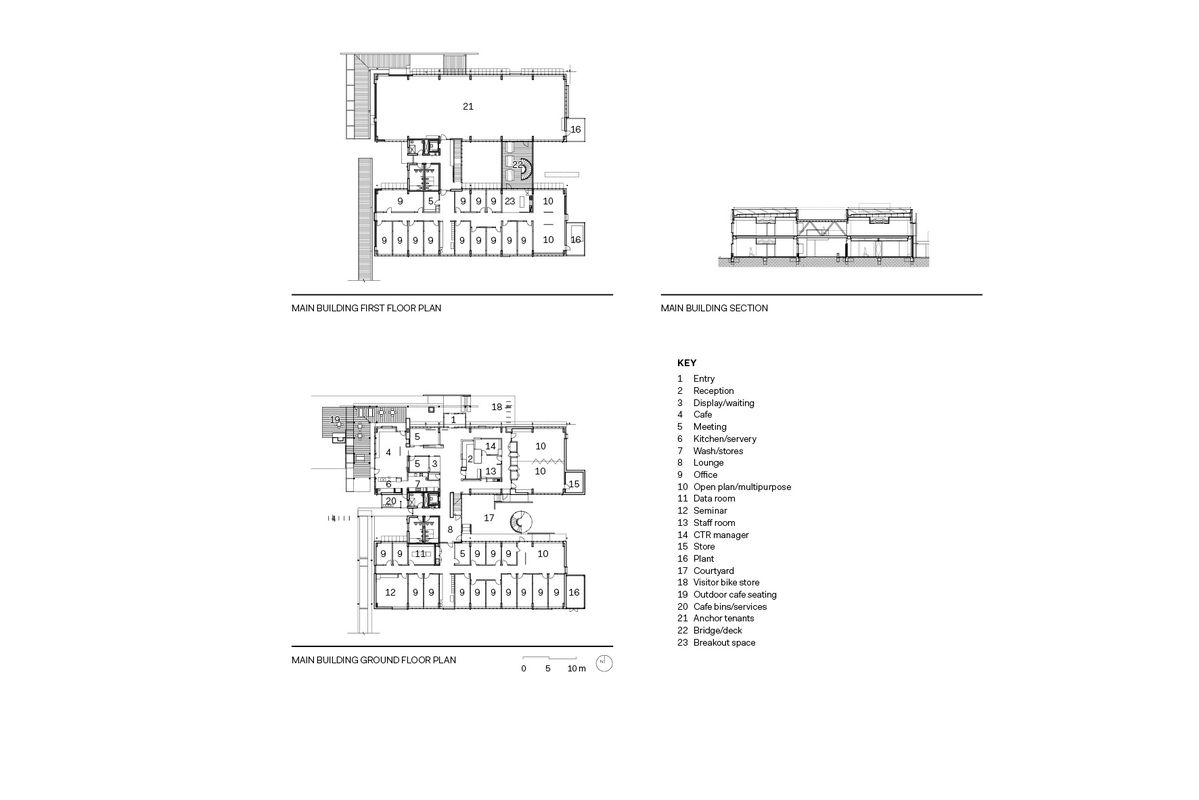

A pair of parallel two-storey rectangular forms house the offices and meeting rooms and are linked by bridges containing the services.

Image: Alice Hutchison

The Western Business Accelerator and Centre for Excellence (Western BACE) is a local government collective enterprise for startup companies and acts as a business accelerator. The building contains offices, a cafe, meeting rooms and space for anchor tenants, plus a separate workshop building placed orthogonally to the main forms. The offices and meeting rooms are housed in a parallel pair of two- storey rectangular forms, linked orthogonally by services and access. As demonstrated by the plans, the logic of the structural order generally enforces alignment of the tenancy/spatial/functional divisions, and in doing so makes the functional order subservient to the structural order. It certainly has the look of rational and thoughtful consideration, with the Corten steel cladding, the patterned concrete block walls, the coloured metal cladding, the diagonal stripes and the mesh skins on the mechanical plant enclosures all accurately composed to a rectilinear order. Yet this elevational composition and the fenestration of the scheme announce an “order” that is not aligned directly to the spaces, functions or structure. There is a De Stijl-like “independence of surface” theme played out both internally and externally; however, by not engaging the functional dispositions in this “independence,” the spaces and the contained functions are inconsistently sheathed in this compositional imagery. The tensions and differentiations of these functional operations (or opportunities) do not activate the plans, forms or surfaces. The spaces are not developed from Alvar Aalto’s spatial manner, where his “ordering sensibility appears to have produced representations of difference.”3 Certainly the plans, although structurally repetitive, don’t indicate any relation to Mies van der Rohe’s works, where the intention is in “providing ‘a ground for the unfolding of life,’ suggesting that the architect be a catalyst for the process of becoming.”4 Nor does the planning deploy the Corbusian schema, where we occupy the contrasting phenomena of structure and enclosure. Is the logic of the structural order of the precast panels to be read as independent, possibly universal? Is the relationship between structure and enclosure to be read as a partnership in the making of these spaces?

The workshop building is differentiated from the main building by the repeated motif of diagonal yellow stripes along the length of its facade.

Image: Alice Hutchison

If, as Tafuri states, “every new architectural work is born in relation – no matter whether of continuity or antithesis – to a symbolic context created by preceding works, freely chosen by the architect as terms of reference for his themes (such that) every architecture has its own critical nucleus,”5 what are the critical intentions of the Western BACE building? What have the architects done with the terms of reference that come inescapably with this work of rectilinear late modernism/De Stijl? I mention these reflections as I see this critical process as most important, and yet it is largely neglected in much recent extremely professional and competent work. Writing of some of Paul Rudolph’s works of the 70s, Tafuri has observed that they represented “an extreme situation: between critical eclecticism and pure play,”6 and I feel that this work, as with many current projects, may have missed the opportunities of the former and been engaged somewhat more safely with the latter. Is much of our architectural production now leaning on the idea that architecture is defined as what architects do?

I am writing about a project whose societal worthiness, professional competence and functional and spatial capabilities are accurate and reasonable. Yet I am searching among these responsibilities for engagement with the positive questions of “why.” Why use this material version of late modernism? Is this material diversity about identity, or are these materials simply itemized? It seems to me that their compositional evenness plays against the essential tensions of gathered identities. The two formal accents to the street elevation contain plant and chair store, but there is no Pompidou Centre services comment here. The yellow truss must feel its Pompidou Centre heritage, but here it does not liberate space from structure. If (functional) identity is a compositional tool, why are the two major forms identical in terms of structural order and scale? Recently reading Tafuri (both directly and through Anthony Vidler), I found that discussions of architecture as an ideology, a critical means and a discursive process seemed to offer an attitude to architecture’s role as a valuable cultural practice. If you carry a critical attitude to help defend design from the undeniable forces of production, then your work will embody this critical stance. Inherent in this reflective practice is alleviation from the presumption, or accusation, that “architecture is what architects do.” Certainly the early work of Six Degrees engaged in these critical discussions, as much of their “found object” design/building technique forced this propositional enquiry with regard to identity and function. Materials were reinvested with value and identity and the spaces, the structure and the enclosure were unavoidably implicated in this reinvestment.

The arrangement of elements on the northern facade, including Corten steel, coloured metal cladding and fenestration with black framing, is reminiscent of a De Stijl composition.

Image: Alice Hutchison

Six Degrees Architects’ history of working with found material has given it a finely honed compositional ability and this has allowed the practice to get all the relevant and enlistable building elements to join in. With this level of material and compositional knowledge, the finished building is certainly competent and acceptable (there’s that qualification again). However, to discuss work in a professional journal – where there is no need to be self-congratulatory – we need to use the work as a source of investigation into the nature of architecture and the role of architects. We need to discuss issues in a context larger than the building. This “acceptability” deflects us too easily, almost readily, from critical enquiry. One is not encouraged to search or engage outside the usual assumptions of cleanliness, order and clarity that come rather naturally with this process of thoughtful building.

Looking at the images and drawings of the scheme, it is clear that the project is justified by professional competence and functional discipline, with accents of colour, material differentiation and detailing that operate as layers upon this skeleton of structure and discipline. Here I feel I could rephrase Colin Rowe, described by Anthony Vidler as writing in 1959 that “[Late] Modern architecture [is] now ubiquitous, an ‘official art’ rather than ‘the continuing symbol of something new, [Late] Modern architecture has recently become the decoration of everything existing’” and in 1947 that “The difference is that between the universal, and the decorative or merely competent; perhaps in both cases it is the adherence to rules which has lapsed.”7 We as architects need to put some critical rules back into play. This can be done both individually and collectively, and we need to have something to say. Architecture is more than simply building competently and thoughtfully. We all know this and we know that this cultural responsibility is essential to the true value of architecture.

Western BACE by Six Degrees Architects received the Allan and Beth Coldicutt Award for Sustainable Architecture in the 2016 Victorian Architecture Awards.

1. Anthony Vidler, Histories of the Immediate Present: Inventing Architectural Modernism (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2008), 178.

2. Manfredo Tafuri, Theories and History of Architecture (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1980), 108.

3. Detlef Mertins, Modernity Unbound: Other Histories of Architectural Modernity (London: Architectural Association, 2011), 142.

4. Detlef Mertins, Modernity Unbound, 142.

5. Manfredo Tafuri, Theories and History of Architecture, 109.

6. Manfredo Tafuri, Theories and History of Architecture, 129.

7. Anthony Vidler, Histories of the Immediate Present, 96.

Credits

- Project

- Western BACE

- Architect

- Six Degrees Architects

Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Peter Malatt, Simon O’Brien, Shol Nicholas, Jo Tinyou, Robyn Ho, Laura Tindall

- Consultants

-

Acoustic engineer

David Dolly

Building surveyor PLP Building Surveyors & Consultants

Environmental consultant Sustainable Built Environments

Landscape architect Tim Nicholas Landscape Architects

Quantity surveyor Slattery Australia

Services engineer SPA Consulting Engineers

Structural engineer George Apted & Associates

Traffic engineers Ratio

- Site Details

-

Location

Melton,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Commercial

Type Workplace

Source

Project

Published online: 27 Jun 2016

Words:

Des Smith

Images:

Alice Hutchison

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2016