The Venice Architecture Biennale is a lovely party. Soaked in sun, speed boats and Prosecco, it is also a fantastic place to view a global cross section of contemporary architectural thinking. This year, Rem Koolhaas’s tilt at the creative directorship has been run like a military operation. Typically, the Biennale’s Creative Director is chosen late and the theme announced even later leaving countries to either scramble to fit in or ignore the theme completely and exhibit architecture as they see fit. Koolhaas, however, was appointed early and opened with a bang, announcing a theme for the Biennale focussing on the Fundamentals of architecture and the evolution of national identity expressed through the architectural lens of modernism – Absorbing Modernity: 1914–2014.

Using the vehicle of the Biennale to add to the architectural cannon Koolhaas has created a research saturated, authoritative body of work. The centrepiece of the Biennale, Koolhaas’ latest research project – Elements of Architecture, completely occupies the Giardini’s central pavilion. Developed in collaboration with the Harvard Graduate School of Design, numerous industry leaders and academics the exhibition defines fifteen ‘fundamentals’ of architecture – floor, wall, ceiling, roof, door, window, façade, balcony, corridor, fireplace, toilet, stair, escalator, elevator and ramp. Rather sadly neglecting the column, as pointed out astutely by Professor Paul Walker (University of Melbourne), the project is documented in an accompanying fifteen-volume book.

Basking in the Venetian sun at Maison Dom-Ino.

Image: Peter Bennetts

While Elements is a fascinating stand-alone exhibition, its position in relation to the greater Biennale deserves to be questioned. Although the ambition for the Biennale is laudable, Koolhaas’s creative directorship perpetuates a particular line of modernist thinking. The entrance to Elements is flanked by a full-scale, plywood replica of the Maison Dom-Ino. The house was intended by Le Corbusier as a framework for living, the gaps to be filled in and made whole through inhabitation. The plywood Dom-Ino, turned into sculpture and objectified as art, is impossible to inhabit meaningfully. Instead it is fleetingly occupied, at ground level only, by an ever changing array of well-heeled, lounging architects.

The presentation of the Dom-Ino as an object to be admired as opposed to a framework for life is echoed within the Elements exhibition itself. The introductory room to the exhibition showcases an expansive selection of canonic architectural texts from Vitruvius’s Ten books on Architecture to Giedion’s Mechanization takes Command bluntly implying the fifteen-volume Elements of Architecture is the next text in the succession. Like Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson before him, whose 1932 MOMA exhibition and accompanying book The International Style monumentalised a particular aesthetic that became irrevocably connected with Modernism, Koolhaas’s Biennale monumentalises a global contemporary response to modernity.

The theme of Absorbing Modernity looked exciting on paper but feels overly constraining in execution. A significant number of national pavilions chose the historical timeline as the lens through which they visually documented the expansion of modernism in their countries. In some cases this technique was successful. Mozambique, in its first Biennale, produced Architecture between Two Worlds, a simple three-strand timeline that clearly positioned international modernism in relation to the development of Modernism in Mozambique and traditional modes of construction and expression as they evolved over the past century. For an audience unfamiliar with the architecture of Mozambique, the exhibition provided a clear insight. However, many countries displayed a timeline of Modernist architecture that is all too familiar and the overall impression is one of repetition and retrospection.

The first ever Mozambique exhibition at Venice Biennale, Architecture between Two Worlds.

Image: Courtesy Mozambique curatorial team

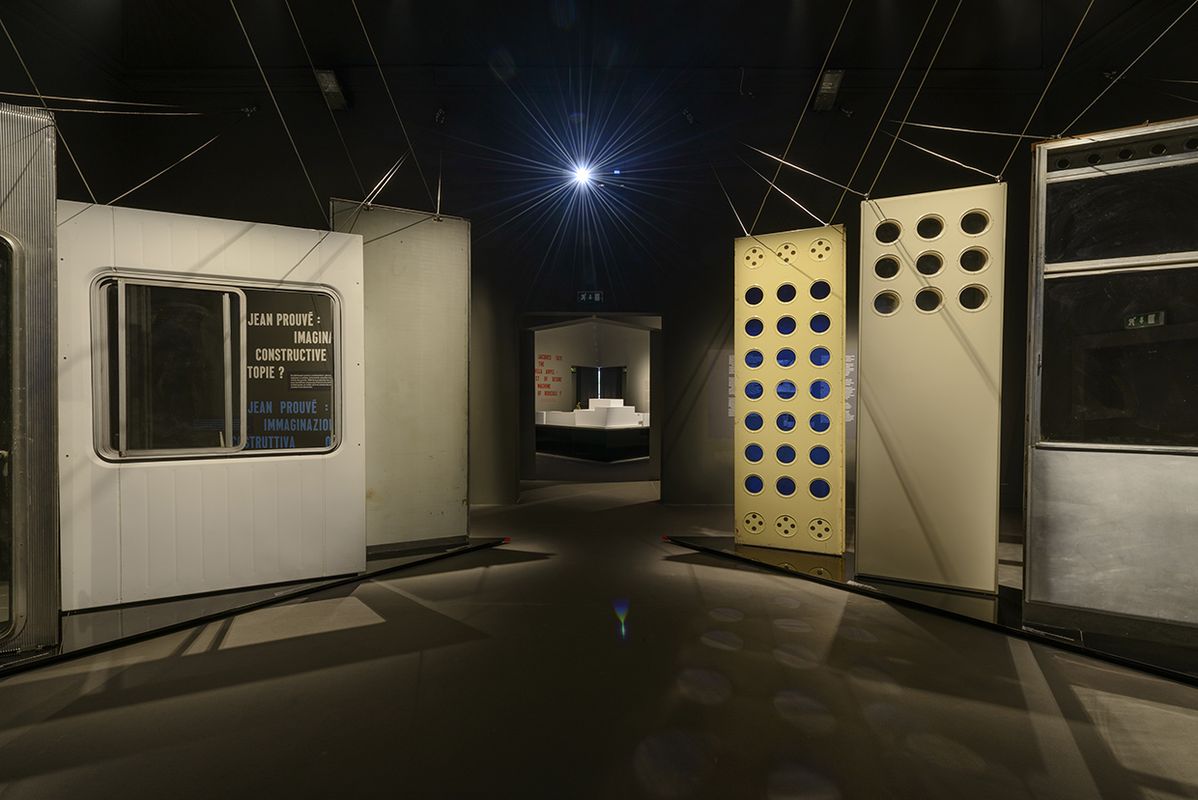

Some countries dealt with the historical legacy of Modernism more cleverly than others. Great Britain provided a joyous pop celebration of Modernism, echoing the euphoria of Alison and Peter Smithson’s search for a more humane modernism with their exhibition, A Clockwork Jerusalem. And France’s exhibition Modernity: Promise or Menace?, used the clever humour of the Villa Arpel, designed by Jacques Lagrange for the 1958 French comedy Mon Oncle, as a device to highlight the promise and the menacing social reality of modernist architecture and the processes of modernisation.

French exhibition Modernity: Promise or Menace?.

Image: Courtesy La Biennale

As architects we are conditioned to love the Modernist aesthetic, to live and breathe it. We are educated on a diet of the Maison Dom-Ino and the Barcelona pavilion, of Loos and Corb and Mies. However, it is important to place the aesthetic in political, social and cultural context and to give the work richness beyond the image. The countries that dealt with the culture and processes of Modernism and modernisation as opposed to the aesthetics of Modernism provided the most interesting counterpoints. Israel and Canada in particular provided food for thought addressing the processes of modernity as opposed to the aesthetics and Austria and Poland explored themes of politics, power and monumentalisation.

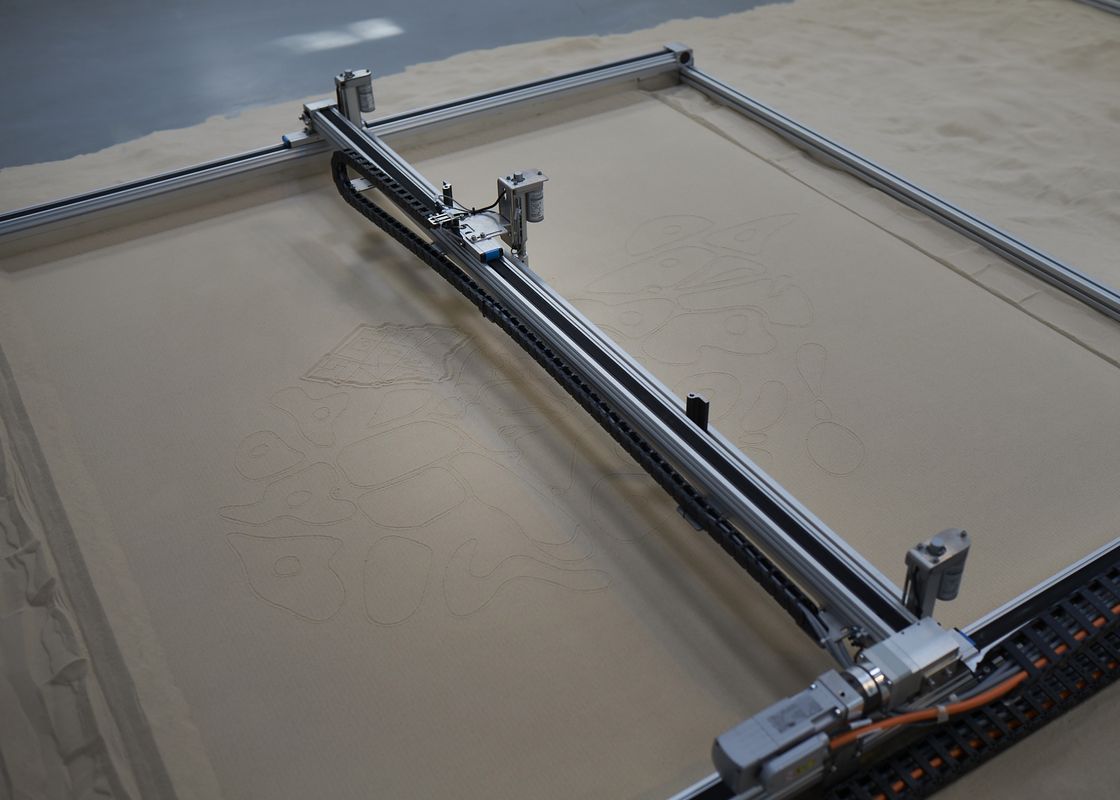

The Israeli exhibition, Urburb, utilised the Modernist preoccupation with the aerial view to articulate Israel’s history of dispersed urban form inspired by the garden city and the modernist suburb. Using four plotters to draw in sand shipped to Venice from Israel, the exhibition described Israel in plan at four scales – the scale of the country, the city, the neighbourhood and the building unit. The sand plotters depict moments in time delineating Israel’s changing urban form. The mesmerising movement of the plotter stylus provided respite from the information heavy Biennale. Between each drawn moment the sand is erased creating a tabula rasa, clearing the ground for the next drawing and providing a moment of contemplation.

Israeli exhibition Urburb.

Image: Courtesy La Biennale

The Canadian pavilion, Arctic Adaptations: Nunavut at 15, exhibited rigorous design research exploring the Nunavut region of Canada, one of the world’s most remote and climatically harsh territories. Not only did the exhibition provide a beautifully presented documentation of the existing conditions and history of this remote area, it also presented projective architectural research investigating the significant issues the region faces. Addressing health, housing, arts, education and recreation, the research takes the form of five architectural proposals articulated at three scales and animated from above by a projection that adds information about context, circulation, wildlife, landform and occupation. Each project was developed by teams comprised of a Canadian school of architecture, an architectural office with experience working in the far north and a Nunavut organisation. In a timeline saturated Biennale it was refreshing and engaging to see projective architectural proposals founded on compelling contextual research and analysis.

Five architectural proposals for Nunavut articulated at different scales.

Image: Courtesy La Biennale

Themes of politics and power were cleverly played out in the Austrian pavilion and the Polish Pavilion. The Austrians, with their exhibition Plenum: Places of Power, simply and effectively presents 196 national parliament buildings on its walls at a scale of 1:500. The buildings, taken as artefacts of national identity, are stripped of context highlighting the scale and form of each building – Australia, by a significant margin, has the second largest surface area. Without context the parliaments become ornament, a comment on contemporary politics perhaps?

The tongue in cheek tomb of Rem Koolhaas.

Image: Courtesy Polish pavilion curatorial team

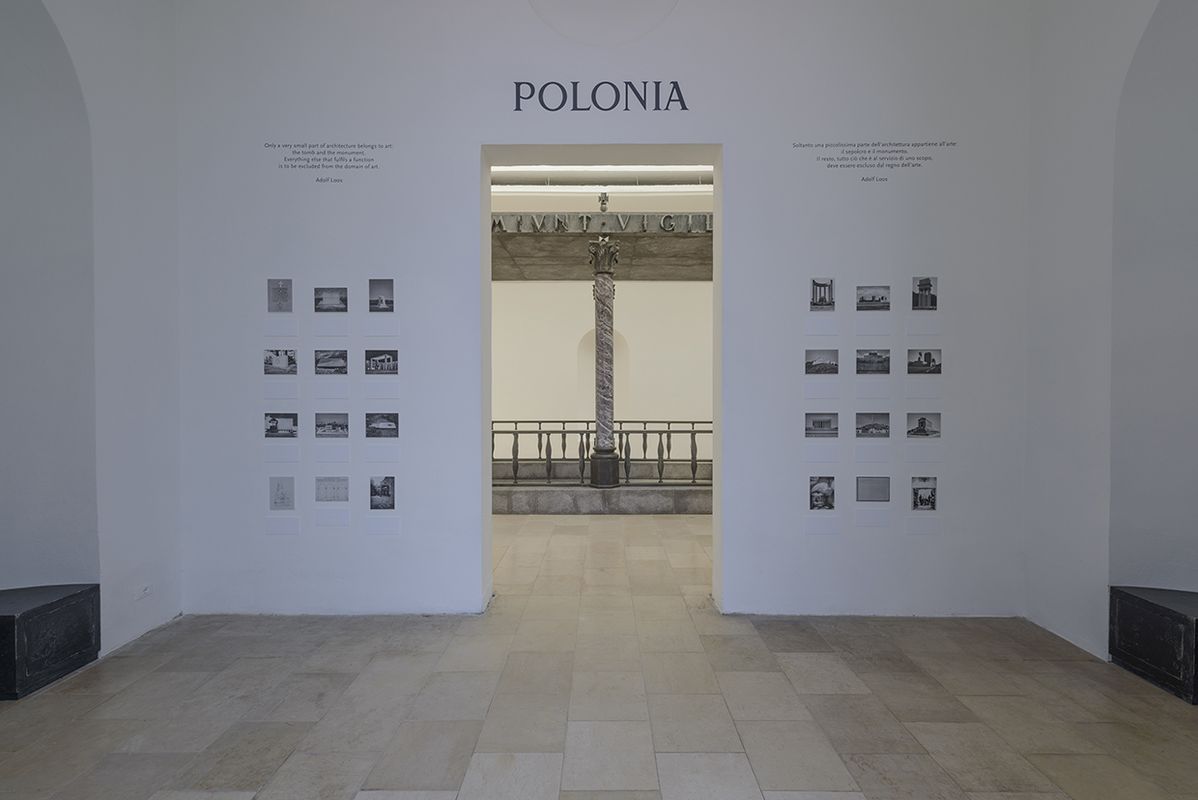

The Polish exhibition, Impossible Objects, presents a full scale facsimile of the burial crypt of Marshal Józef Piłsudski, a significant 20th century Polish leader who was instrumental in the creation of an independent Polish state. The existing tomb is a heavily symbolic work incorporating materials designed to evoke national pride and contradictory architectural elements – a neoclassical base and a slab-like horizontal canopy at the top. Re-presented for the Biennale these architectural elements are amplified as a commentary on Poland’s contradictory relationship with modernity and the early modernist period – tradition versus modernity, the past versus the future, etc – and an exploration of the relationship between architecture, power and death.

The entrance to the Polish pavilion is flanked to the right by monuments to fallen heroes and, to the left, by the cemetaries of Scarpa and Asplund and the tombs of famous architects – Mies, Aalto, Le Corbusier and Loos. These images are framed by a quote from Adolf Loos which reads, “Only a very small part of architecture belongs to art: the tomb and the monument. Everything else that fulfills a function is to be excluded from the domain of art.” The curators, interested in the fact that Loos designed his own tomb numerous times, asked several architects if they had ever given any thought to the way they would be commemorated. Koolhaas replied to the question by stating “I have no sympathy for death”. So the curators cheekily designed a monument for him in the form of the CCTV building and placed him next to Loos. If only more pavilions had bucked the party line and played irreverently with the Biennale’s theme.

One of the great strengths of this year’s Biennale is that it provides an excellent body of architectural scholarship devoted to modernism and its global evolution. The Monditalia exhibition, the third cornerstone of Rem’s Biennale, is a beautiful, expansive example of this. Taking up a large section of the Arsenale, the exhibition is devoted to contemporary architectural thinking in Italy drawing on Italy’s historical significance in relation to architecture culture. Koolhaas’s Biennale places architectural history front and centre in the international architectural consciousness. As a body of work it is a great foundation to build upon. However, this has come at the expense of the projective architectural project and engagement with contemporary architectural concerns. Like an old photograph, this year’s Biennale resonates nostalgia. With the multitude of issues currently facing the profession – gender equity, sustainability, increasing economic and financial pressure, questions regarding the future and form of architectural practice and so on and so on – turning the Biennale into a factory for the production of historical timelines seems like a missed opportunity.