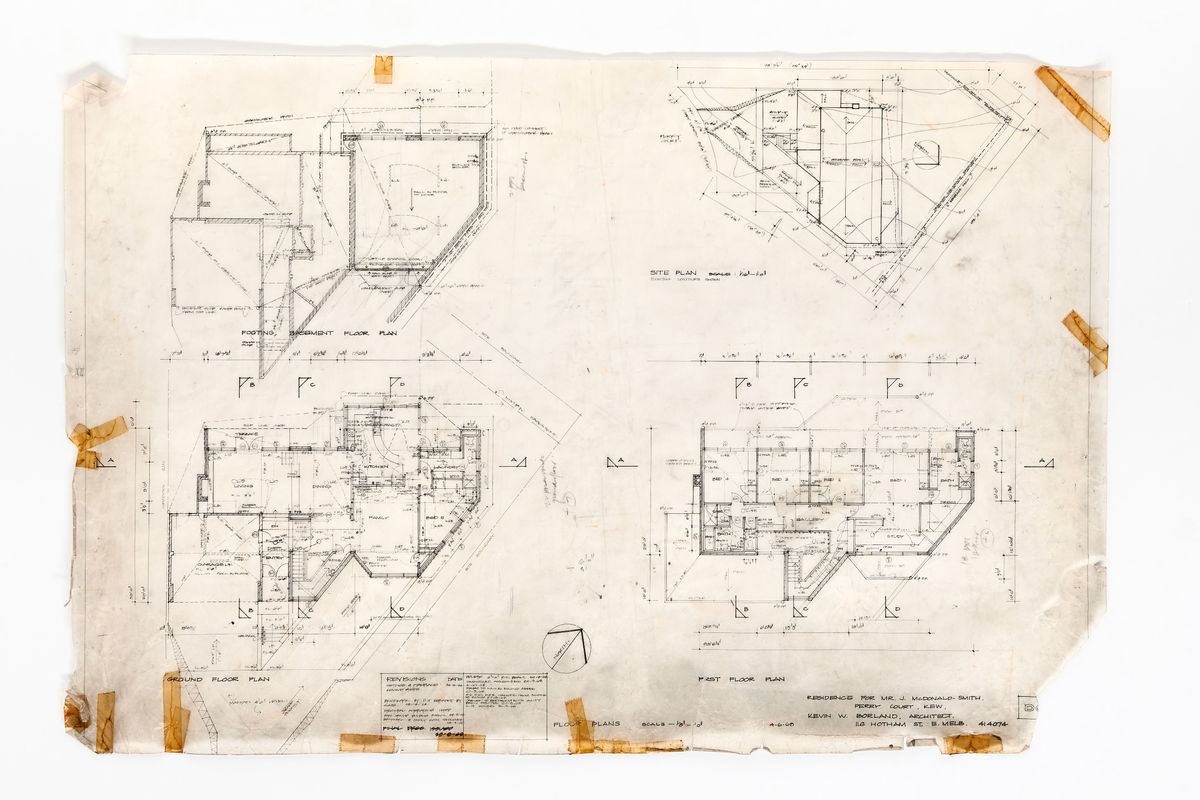

The McDonald-Smith House (1969) in Melbourne’s eastern suburb of Kew, while not a particularly well-known work of modernist architect Kevin Borland (1926–2000), nevertheless presages his celebrated mature domestic work of the 1970s in many ways. A reasonably large house in an affluent suburb, it sits at an interesting junction between the experimentalism of Preshil Junior School Hall, also in Kew (1962), and the complex geometry, rugged forms and textures characteristic of the later work and heralded by the Paton House in Portsea (1970) on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula. Borland had travelled overseas in 1966, visiting England, Holland, Scandinavia and Russia, and on his return the impacts of his travels were played out in the brutalist Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Centre (1968–69), designed in conjunction with Daryl Jackson. That building’s recalibration of form and texture had an impact on the McDonald-Smith House, evident in the cantilevered bay on the front elevation, the extruded kitchen and meals area to the rear, use of the chamfer and the austere brown brick exterior. But there are also glimpses of the Paton House here – particularly in the interior spatial arrangement – although at first glance the two very different plans would seem to belie this connection.

The McDonald-Smith House is stretched across the width of an elevated, wedge-shaped site and squeezed between two street frontages. Its entrance is at the base of a short cul-de-sac, while the rear elevation, with its long bank of uniform windows, commands impressive views to the north. The rectilinear plan and generous glazing on both elevations ensure that the whole house is filled with light. There are no dark corners or lost spaces.

Intricate joinery separates the living room from the dining room while allowing for a visual connection.

Image: Dianna Snape

While the planning appears to be controlled by a formal grid, the spatial organization of the interior is fluid and experiential. Designed around the rhythms and needs of everyday family life, this is a careful response to the client brief and the opinions of the four children. It is here that we can see the sort of thinking that was given much freer rein in the holiday house in Portsea. There, the entrance creates a node around which the bedrooms and living rooms fan out. At the house in Kew, a similar effect is achieved by the manipulation of circulation patterns through the grid. Stepping through the front door to a small vestibule, you can proceed two ways (or three if you count the door to the immediate left, which opens into the garage). Straight ahead and down to a slightly lower level you enter the living room that looks out to the rear garden. In the corner of this room to the right, you pass up a short, curved staircase to the dining room. The detailing of the stairs is ingenious and simple; the timber treads rest on the tops of wide ply boards that form the curved staircase screen. Above, another vertical timber screen atop inbuilt cabinets separates the living room from the dining room while providing visual connection between the two spaces. The dining room, faced in vertical timber boards, has access not only to the living room but also to the kitchen and hall.

If you turn right from the vestibule, you enter the double-height hall, clad in pale timber like the dining room. Above, a cantilevered passage in front of the row of first-floor bedrooms protrudes into this space and is faced with another timber screen that extends to the ceiling; this arrangement is recast as a mezzanine sleeping space in the Paton House. The dramatic effect at the McDonald-Smith House recalls the “living halls” of Arts and Crafts architects like Walter Butler and Rodney Alsop, the latter’s Glyn in Toorak (1908) being a pertinent forerunner. The hall leads to another family room ahead that overlooks the court and abuts the kitchen; it is thus the hub of the house, around which revolves a generous and fluid space. However, panelled sliding doors can close off the dining room and the family room, separating the private spaces from the more ceremonial or public space of the hall. Here, again, there is precedent in Melbourne’s Arts and Crafts architectural experiments, particularly in the work of Harold Desbrowe-Annear, who frequently used panelled sliding doors to manipulate the interior spaces and circulation patterns of his domestic interiors.

The dining room is centrally located, with access to the living room, kitchen and main hall.

Image: Dianna Snape

While on plan the house might appear somewhat rigidly formal, Borland has inserted into its basic geometry a surprisingly fluid and extremely artful series of open and closed spaces. It is so well planned that almost nothing has changed in forty-seven years.

As with Borland’s architecture in general, it is the detail of the McDonald-Smith House that beguiles you. Like Desbrowe-Annear and Alsop, Borland uses the structure of his interiors as their only ornamental feature, an aspect of his architecture that became more marked in later work. For example, the bulky top of the timber handrail of the staircase has a double thickness so you can slide your hand along in the groove as you go up the stairs. Although the timber detailing gives the interior a feeling of richness, colour and vibrancy, it is in essence quite simple and enhances the planning of the interior and the expression of each space. It also turns the transitions from space to space into memorable experiences. This is particularly evident in the transitional zone from the living room up to the dining room, via the timber staircase. It is also apparent in the passage outside the bedrooms on the upper floor, where the space is enlivened and given character by the tall screen, through which you look into the hall below. The small shifts in level that mark the transitions from the vestibule to the living room and hall are also emblematic of Borland’s attention to the lived experience that his buildings afford. In all these ways, the McDonald-Smith House is typical of Borland’s stance as a modernist architect, expressing his humanist concern that architecture reveal and enhance the pleasures and patterns of everyday life at both programmatic and formal levels.

Kevin Borland (1926–2000) was an Australian architect who was recognized for his regionalist take on the international modernist stance. In his formative years, he spent time working on the Small Homes Service under Robin Boyd and Neil Clerehan. In collaboration with architect Daryl Jackson, Borland designed the Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Centre (1968–69 ), which is Victoria’s most notable example of brutalist architecture.

Source

Project

Published online: 12 May 2017

Words:

Harriet Edquist

Images:

Dianna Snape,

From Doug Evans et al, <i>Kevin Borland: Architecture from the Heart</i> (RMIT University Press, Melbourne), 2006.,

Kevin Borland.

Issue

Houses, December 2016