When I commenced my career I was advised by people I respected that I should get experience by working in a large practice, which I did. However, I also worked on private commissions to build my courage and avoid mediocrity. Driven by a philosophy of high risk and high drama, I soon found myself converting a historic canal-side terrace in Amsterdam. My clients wanted to test every design rule. Despite the distance, I was able to connect my clients with their dream. From that moment my objective was to enable my clients to give life to their dreams.

Around this time I was invited to design a beach house in Vanuatu. My client had purchased land that we later discovered had existing plans and a design for a beach resort. My client became interested in developing this resort; however, the existing designs were for a faux traditional thatched-roof beach resort. Without knowing how to build in this foreign land, I encouraged the client to join me in developing another dream, equally fuelled by risk.

My first problem was how to convince the client that the primitive hut aesthetic was imported, trashy and clichéd – not exactly the definition of vernacular. But what is vernacular? I didn’t know and nor did my client, but he was enthused by the question.

Slowly I began to lead him away from the conventional “mother tongue” definition, and replace it with an idea about architecture rooted in a sense of place. For the project, this meant gaining the trust and ambition of those who lived there. I sought to work with symbolism they could relate to and use materials within walking distance, allowing their skills and craftsmanship to inspire and teach me. I slowly began to gain the respect of my client’s Ni-Vanuatu business partner.

My final design presentation was delivered in a boardroom filled with solicitors, accountants, builders and clients. They patiently listened to my story as I resisted being overwhelmed by fear. Then, with almost unbelievable speed, the project was accepted. The dream was becoming a reality.

Then came the chaos. The documents were prepared without problems or surprises, but also without the advice of structural engineers or service consultants, which my clients refused to engage. I had to call in favours to ensure quality. I remained on my toes for the entire project, as every decision was made on the fly. Necessity, materials and lack of appropriate skills determined most changes. I was constantly weighing up risks and carefully adapting to suit the capabilities and resources in Vanuatu.

There was no leadership so the project proceeded unevenly, booming then stagnating. Drawings were ignored. Inappropriate set outs had to be corrected again and again without a surveyor overseeing it. This resulted in the improvised use of a canvas template and hand-cut stakes.

Cultural issues intervened as the local Ni-Vanuatu business partner and his team coped poorly with receiving instructions from a lone woman. They would turn their backs to me or deliberately speak in French, believing that I couldn’t follow the conversation. I felt exposed on site and in hindsight was probably naive to think I was safe.

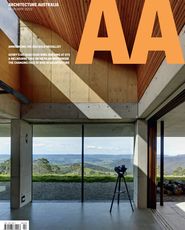

My biggest challenge was knowing where the money was going. The project eventually ground to a halt and for months its future was uncertain. It was only after I invited one of Australia’s leading architectural photographers, Peter Bennetts, to come and photograph the project that it took on a new life. On returning to Melbourne, Bennetts and I staged a photographic exhibition that was very successful. With this success the impetus to complete the project returned. I am now at the stage of custom-designing light fittings, joinery and furniture for the project.

I have been asked why I put my life on hold to see this project completed, but each day we struggle to deal with those who want to take mindless shortcuts. Though I sometimes wonder whether the risk has been worthwhile, the thought is fleeting and I can’t imagine working any other way – to me, people’s dreams are too important.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 30 Apr 2015

Words:

Kristin Green

Images:

Courtesy of Kristin Green,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2015