Standing among the ejected smokers of Docklands’ shiny office developments and listening to Docklands SoundWalk, a ten-stop iPhone tour running over the summer, you are invited to refigure these surroundings as the head of the meandering Yarra River – once a hunting ground of the Wurundjeri and Bunurong people, then a shantytown of bloody slaughterhouses, a busy dock marked by criminality and union struggles, and by the 1990s a container-ridden wasteland ripe for redevelopment. Everywhere, it seems, our experience of built places promises to be transformed, for better or worse, by an overlay of digital, ubiquitously accessible apps. These apps for smartphones and tablets are assuming a number of guises to inform the architecturally minded user – including the tour guide, design tool, pocket encyclopedia, marketing brochure, tutorial and game – all attempting to expand our experience of a city or building through an overlay of digital content.

This is still a fluid terrain, but we see three dimensions defining the space of mobile digital tours. First is authorship, from the more experimental, ephemeral and subjective guides – which often explore a range of media, from sound to film and manipulated images – to the more authoritative or institutional offerings. The second dimension is scale, from the individual building to a city-wide tour. And the third is the level of user control or agency, from highly scripted guides, which take you by the hand along a predefined route with carefully sequenced content, to the nonlinear pick-and-mix tours usually derived from existing databases or encyclopedic resources and configurable by the user (albeit usually in a constrained way).

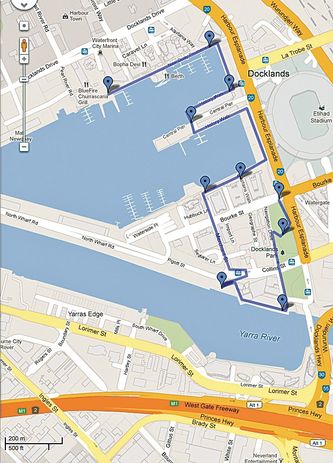

A stop on the Docklands SoundWalk in Melbourne.

There is nothing new about guides for cultural tourism, and well-recognized brands like Lonely Planet are releasing a number of city guides for the iPhone, including a walking guide to Paris that uses a conventional map format with stops that activate a slice of patter from a French-accented tour guide against a collage of background sounds supposedly evocative of the city’s streets.

But a number of other guides published in the last year are catering far more exclusively to the niche market of architecture and design. These are not just driven by new technological possibilities but seem to be catching the wave of archi-tourism that has become known as the “Bilbao Effect.” Domus, for example, is publishing a series of city guides, with London, New York, Shanghai and Berlin currently available. The London edition gives you a comprehensive list of notable buildings in Greater London, spanning from the 1930s to the present. You can search by architect, look up design outlets, plot your own route or follow one of four preset tours. We tested the description of the Isokon building, designed by Wells Coates in 1933, and found that it was solidly covered both on its history and the life span of the building, including its recent conservation. This is unlike many other architecture guide apps appearing on the Apple App Store which, as many reviewers have been forthright in pointing out, are not worth the pixels they are built with.

Similar in design and intent to the Domus app is the newly released Vic-Heritage app, which gives a listing of registered sites in Victoria, each with an image and a precis of a heritage report. You can search and plot sites from the database on a map to find examples near to your current location, or follow a recommended tour (like Ghosts of Docklands or Melbourne Murals). And in a gesture to Web 2.0, like most apps of this sort, it solicits user comments and content. The MyBurb project currently being developed by the ABC uses augmented reality technology (Layar). It attempts to take user-generated content to another level by creating more organic guides of places – Redfern and Millers Point are in progress – and aims to combine people’s own contributions with ABC archive material to create an interactive history of Australian suburbs.

In terms of other, more subjectively authored and less encyclopedic guides, The Sound of Buildings app presents itself as a walking tour of ten significant buildings in Melbourne. In an attempt to offer a multiplicity of views rather than authoritative singularity, each building is represented through a gallery of site images accompanied by different voices, usually including a designer, an engineer, a user and a child. The material is well selected and constructed, but is perhaps better consumed before or after visiting, as there is no direct indexing of content to elements in the site and little clue as to how it might be consumed during a walking tour. Our own observational studies have shown that people find the consumption of long stretches (over one minute) of disconnected content in situ beyond their comfort threshold.

A few app guides are beginning to appear for individual buildings as well. This is an eclectic and serendipitous mix, with some from recognized cultural institutions and museums, like the guide to Zaha Hadid’s Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati by Planet Architecture. It offers plans of the building and an interview with Hadid telling us how “architecture, in a good way, can restructure society.” Others have a more singular focus, like the guide to Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House 22 in LA and the disconcertingly detailed reconstruction of Hitler’s house on the Obersalzberg.

A map of stops along the Docklands SoundWalk in Melbourne.

Returning to the Docklands, where we began, this tour has been created through QR codes, embedded tags that are scanned by a mobile to trigger the downloading of information at each stop. The Society of Architectural Historians has created a tour of Chicago architecture using the same tagging technique. This reliance on physical signs seems a little counter to the spirit of mobile delivery. However, it brings a simple directness through its hardwired links to physical location that demand your presence on the site. This contrasts with the greater freedom but less directive approach of database-driven and encyclopedic apps.

No matter the mode of delivery, this emerging genre of touring apps is rushing to embrace the functions of Web 2.0- and Web 3.0-based mobile and ubiquitous connectivity. This is enhancing their immediate gloss but may well miss the challenge of actually assisting people to experience and make sense of past and present places in ways that conventional media cannot already do. The promise of multiplicity and organically created material is flexibility and difference, but it sometimes brings confusion that threatens sustained uptake and use. And at a deeper level, we might ask: Are digital touring apps offering a retelling of history that sugar-coats wholesale urban destruction and insensitive redevelopment?

Hannah Lewi (Faculty of Architecture Building and Planning) and Wally Smith (Department of Information Systems and Computing) wrote this review based on their experiences at The University of Melbourne creating digital prototype tours in Melbourne, focused on education – either for the general public or for university students. These include guides for the Shrine of Remembrance, the Royal Botanic Gardens and the nineteenth-century architecture of central Melbourne (in the Formative Histories Walking Tour app).

1 “Reality is Plenty, Thanks,” Paola Antonelli (ed.), Talk to Me: Design and the Communication between People and Objects (MoMA, 2011).

This article was originally published as part of a dossier in the March 2012 issue of Architecture Australia that discussed whether the architecture profession is losing ground.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 25 Jun 2012

Words:

Hannah Lewi,

Wally Smith

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2012