The indefatigable optimism with which architects repeatedly enter competitions is astounding. Not only does each entrant believe the winning scheme will be theirs, they have confidence that the jury will be sufficiently impartial and wise to recognize this and will adhere to the selection criteria stated in the brief. I’m not suggesting architectural juries are incompetent or corrupt, but they are unavoidably made up of people with existing allegiances and preferences that colour the selection process. Worse, few competition winners see their entries realized, even when a commission is promised. This is especially the case in Australia – think of Sydney Olympic Village, the MCA, the Ultimo Pool and so on. The fact that entering competitions is akin to gambling (with only slightly better odds for closed competitions) has, however, once again not deterred our sanguine profession.

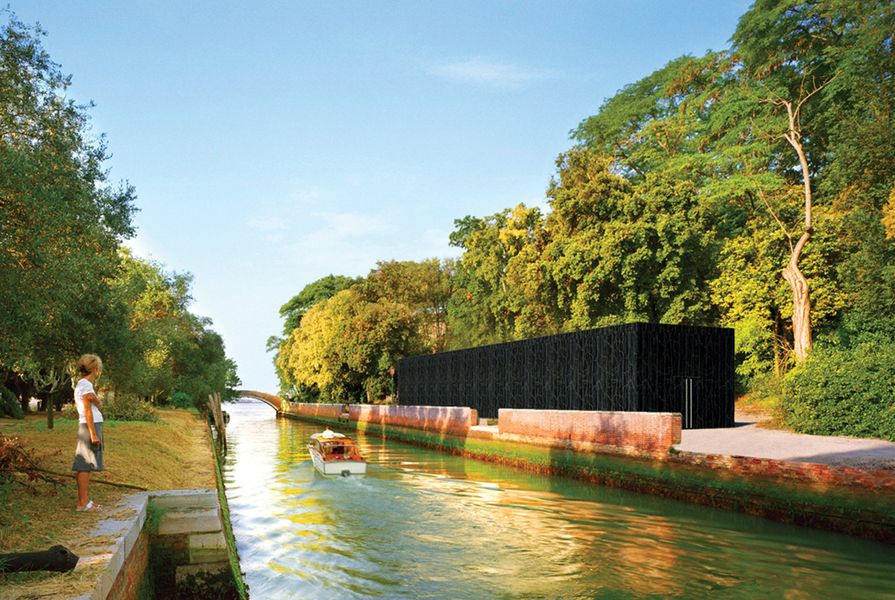

Iredale Pedersen Hook’s scheme.

The Venice Biennale New Australian Pavilion Di Stasio Ideas Competition received over four hundred entries, fifty-six of which were shortlisted for the exhibition at Heide Museum of Modern Art in 2008. The competition was sponsored by arts patron Rinaldo Di Stasio for the express purpose of adding to an ongoing momentum of support for rebuilding the Australian Pavilion. This is not an official competition with the building of a new pavilion as its result, nor is it endorsed by the Australian Institute of Architects or the Australia Council for the Arts. Despite this, and despite the vagaries of competitions generally, there are good reasons for the enthusiastic response.

Firstly, there was no registration fee and the competition was open to both registered architects and pre-professionals, with prizes including travel and accommodation to this year’s Architecture Biennale. Secondly, and this is the main drawcard, the project itself has rich possibilities. In the absence of any client/budget/reality, the competition organizers encouraged “radical architectural solutions.” Entrants could go as far as dismissing the site of the existing Australian Pavilion by Cox and the very notion of a permanent pavilion. Furthermore, the jury – architect and writer Norman Day, photographer John Gollings, artist Callum Morton and architect and urbanist Bridget Smyth – is sufficiently diverse as to be entirely unpredictable. All the conditions are there for an exhibition that promises to be a barometer of unconstrained architectural thinking on urbanism, exhibition spaces and the representation of national identity.

I’d like to report that this has been the result, and well it may be, but the exhibition itself is inscrutable. On first sight it looks good. The exhibition consists of a freestanding triangulated structure, a neat black folded continuous wall within which the exhibition entries are digitally exhibited. The exhibition wall holds up well in the beautiful new gallery extension designed by O’Connor and Houle. Each screen presents the projects of four or five entrants, organized alphabetically. Each entrant is represented by three to six images, one image at a time for several seconds per image. Unfortunately, the screens sit close to each other, and it is impossible to block out the flickering of the adjacent screens as they run through their cycles. It’s a little like watching six televisions simultaneously.

Denton Corker Marshall’s proposal, one of the finalists.

It being mid-week at the time of my visit, and Heide being an out-of-town gallery, the audience was predominantly made up of ladies-who-lunch earnestly trying to make their selection for the People’s Choice Award. With the chance to win dinner at Cafe Di Stasio to the value of $500 simply by voting, there was considerable incentive, but they were falling like flies. To quote, “I can’t bear the flickering.” My two companions, both architects, gave up after a few minutes while I valiantly persisted – I had this review to write. I managed to view the end screens with the help of a piece of paper held to one side to block out the screen adjacent. Eventually, I was told that I could view the images on the website and I gave up, defeated. The bad news is that the images are not on the website, so what follows is a patchy impression of just over half of the entrants.

The “stretched Tasmanian tiger skin” by Grant Amon.

Overall, there was far less interest in the conditions of exhibition than one would expect given the building’s purpose and the desire to improve upon the reputed difficulty of curating the existing pavilion. Several entries acknowledged current curatorial practice, offering straightforward black box/white box schemes, including Denton Corker Marshall’s cartoon of this idea, which was chosen as one of the finalists. Iredale Pedersen Hook and Richard Swanson both divided their schemes into “dumb box for art, roof terrace for party.” The difficulty with the dumb box scheme, as with any interiorized program, be it supermarket or art gallery, lies in the reduction of its relationship with urban context to the manipulation of the imagery or texture of the envelope. With the exception of schemes by Angelo Candalepas and Nicholas Braun, both of which attended closely to the canal and landscape, there was an overwhelming lack of concern for the Venetian setting. Several schemes – Tamara Freibel’s, for example – were presented as isolated and self-referential objects sitting on entirely denuded and featureless white planes.

Tamara Freibel’s proposal.

Matthew Bird’s scheme that resembles “the skull of some ancient dinosaur.”

By far the greatest interest among the entrants was with the formal opportunities of the pavilion. For some, this was an opportunity for tongue-in-cheek Australiana. Grant Amon offered a stretched Tasmanian tiger skin, Todd Hoehn an island pavilion whose plan resembled the Australian continent, and Matthew Bird the skull of some ancient dinosaur. There were numerous landscapey desert-coloured proposals. Others forewent any obvious Australian references and sought instead a pavilion so bold, colourful or plastic that its distinction would lie in its sheer exuberance.

The perforated, curvaceous envelope proposed by McBride Charles Ryan.

Much of this formalist fervour lacks traction because it contradicts the need for a pavilion to show art. Consider McBride Charles Ryan’s heavily perforated and curvaceous envelope. Beautifully rendered, one could be persuaded that the experience of patterned light within the interior of the building would be stimulating, exotic, sensual even. Try to exhibit works of art in there? Forget it. We know that architects of the calibre of McBride Charles Ryan and others whose schemes were more conceptual than practical are perfectly capable of resolving a complex brief when required. They chose not to in response to the provocation of the competition organizers for a visionary proposal.

Given that I work in a university in which our students have great dexterity in digital form generation, I found most of the formal directions more familiar than radical. I was disappointed with the lack of experimentation given to the encounter with art, and with new forms of display and exhibition that exceeded the dumb box. Ditto new ideas about urban context. If the competition is seriously hoping to motivate government and private patronage to value and support a new pavilion, there will need to be evidence of the profession’s ability to provide a building that is both architecturally exciting and a workable venue for art. The failure of the exhibition strategy at Heide MOMA dented some of my optimism that this is the case.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 1 Oct 2011

Words:

Sandra Kaji-O'Grady

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2008