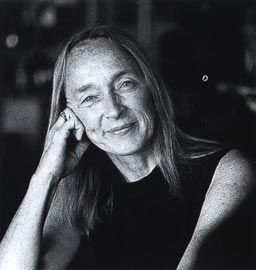

Brit Andresen and Peter O’Gorman at the Mooloomba House. Image: Anthony Browell

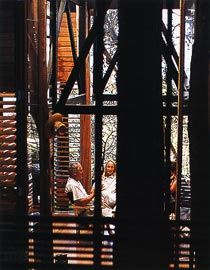

Mooloomba House. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

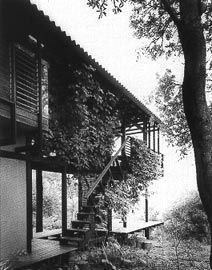

Detail of Mooloomba House. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

In accepting the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal I wish to thank the jury and to acknowledge, with pleasure, the recognition this extends to my collaborations with students and colleagues. In particular, the medal honours the architectural collaboration over the past twenty-five years with my partner and husband Peter O’Gorman, with whom I share this award.

During the years before Peter’s death last year, while we were assembling material for a manuscript, we talked about our work as academic practitioners and reflected on the interdependence and transfer of ideas between our teaching, research and design projects. We also discussed how these ideas developed from our belief that the purpose of architecture is to contribute to making us more at home in the world. Our position was sharpened by what we referred to as the dilemma of Modernism. In an attempt to expand on these conversations I am drawing on our notes to explore the dilemma posed by Modernism and to outline a few of the ideas that have informed our research, practice and teaching.

Twentieth-century architecture is marked by the adoption of abstraction as a way of thinking, with an emphasis initially on functional abstraction and later on formal abstraction. Functional abstraction, or Le Corbusier’s “separation of powers”, is the key to the reinvention of conventional form. The power and potential of abstraction is, however, a two-edged blade. In any retrospective view of the twentieth century it becomes clear that the processes of unfettered abstraction inevitably lead to reductive solutions, “one-liners” where single ideas are reduced to purely functional or formal solutions, and not readily to ideas that encompass more comprehensive experiences.

It is in the very nature of the processes of abstraction to permit the reestablishment of priorities. Functional abstraction involves the restatement of any problem in terms of performance specifications, together with an assumed potential for the unlimited invention of new solutions. The tendency is to establish new and justifiable “hierarchies” that result in the suppression of certain meanings, perhaps traditional, perhaps implicit. In early Modernist thought, the process of reconstruction through functional abstraction was deliberately overlaid with utopian intent and marked by the suppression of traditional composition principles that were perceived to be politically charged. Later, priority inevitably shifted to the economic prerogative. The “guaranteed certainty” offered by the pragmatic solution, plus the suppression of valuebased judgments in the process, has underpinned the ease with which Modernism has been appropriated by capitalism and “the culture of sameness” that we have come to recognise as Western society.

In much contemporary architecture, economic rationalism has eliminated the lyrical, the poetic, the social or the environmental. The built environment faces a dilemma. Productivity, diversity and quantity are greater than at any time in the history of technology, but there is an accompanying loss of value-based quality. This loss of value can be attributed to a failure to appreciate the deeper interactive roles evolved through cultural relationships associated with “things”.

›› In the process of functional abstraction not only is “the object” replaced, but also – through the suppression of the empathic responses – unconscious, accumulated values and meanings gathered as part of human culture and ecology tend to be obliterated or distorted. Culturally evolved “things” are more than just functional objects. Humble as they may be, “things” are the agents of relationships that gather the cultural memory of place and occasion.

This, then, is the dilemma of Modernism. The processes of abstraction hold great power and potential – on the one hand they have the capacity for invention and, on the other, the potential to destroy values and meaning. It seems that there is no going back; the genie is out of the bottle. Modernism is still with us and although almost unrecognisable without its original ethical intent, it continues to drive the design engines of Western society.

Many architects of the late twentieth century adopt the position that the generators of Modernism came as much from the world of art as from engineering. Poetic abstraction can similarly harness the “separation of powers” to delve into the nonfunctional world of ideas. Formal abstraction, however, like the inadequate processes of functional abstraction, tends to result in reductive solutions. The world of abstraction, ideal forms and the body of knowledge draw on what Colin St John Wilson calls the “artificial” or inventive imagination. Instinctive experiential reactions, in contrast, engage the “natural” or empathic imagination.

The current visual novelty of abstractions derived from digital technology, fractal geometry and literary theory is usually the product of inventive imagination rather than empathic imagination. The destructive effect of suppressing the empathic imagination in favour of the inventive is obvious in the excesses of the late twentieth century.

Abstraction, the essential tool used to restate priorities, has subverted the original goals of Modernism that were to seek design quality in the simultaneous balance of the apparently dissimilar intentions of the poetic and the pragmatic of human life. However, in the quest for balance, processes of abstraction also offer enormous potential in the design of the built environment.

There is great value also in ideas that can gather the two forms of imagination together. One such simple idea is that architecture may play a role in structuring relationships rather than destroying them. This is an architecture of interaction between people and their environments, as opposed to an architecture of separation.

Our goal, in teaching, research and practice, has been an interacting architecture where a building acts as an agent in establishing and supporting relationships.

Adrian Stokes uses the term “interacting” in his critical writings as a way of describing a world where all things have an interconnectedness in unity and balance.

Some interconnection is made through the organic and molecular structures of existence and some occurs through common human perception and psychological expectation. When human perception of the environment is at ease with these expectations there is a sense of “fit” between the two. There is both an interconnection and a wish for interaction, and the sense of being “at one” with the world.

Experiencing a building involves many interactions of this nature, some conscious and some below the level of the self-conscious. These can be registered as sequences of experience over time that are gathered and collectively distilled to contribute to “a sense of place”. In the world of design this is a phenomenon unique to architecture.

Architecture can make us more at home in the world by attending to the interaction or mutual fitness between things. When extended to include relation, not only within a building enclosure but also with the surroundings, the total environment forms what Aldo van Eyck might have called “a ladder of interaction” as a wider framework for everyday existence. If, on the other hand, buildings are designed as selfreferential abstractions, the linkages needed to make the relationship integral to experience may be either corrupted or non-existent.

Buildings are made of ordinary commodities. They tend to be the result of prudent adaptations of available resources assembled to fulfil enduring roles of enclosure, shelter and use. Elements such as the wall, the window and the door form important limits in determining possible design options. As Ann Cline describes in A Hut of One’s Own: Life Outside the Circle of Architecture, the placement of a small window in a modest wall can shift the question from simple assembly to include the quality of light on an object, the potential for social theatre, and to establish scale and inside–outside relationships.

This capacity lends ordinary buildings extraordinary design potential. The subtlety that transforms the ordinary (such as the positioning of Cline’s window) derives from two opportunities. The first is the opportunity to create simultaneous readings (“not only but also”) and the second is the opportunity to establish a world of “interaction” where things are interconnected in unity and balance. Obviously these are not the only ideas to drive architectural sensibilities, as opposed to building goals, but they are among the most fundamental. Relationships formed between a building and its landscape can connect, for example, through the place of the window seat, the room, courtyard, garden, hillside and horizon. Here the window seat becomes an active agent in the process of fulfilling the intent where there is an opportunity to align boundary-horizons connecting what is far and near.

The idea that the natural world is made up of the harmonious interaction of bipolar opposites was fundamental to ancient Greek philosophy. The view that the world is an inter-play of forces in dynamic balance is founded on a truly poetic ideal. Perhaps it is simply the urge of the full spectrum of the senses to register a balanced appetite, but as an idea that could generate a visual and conceptual dynamic it had a major impact in art and architecture.

The early timber houses of south-east Queensland can be described conceptually as a Georgian core of rooms (male) surrounded by a Victorian verandah skirt (female).

Another conceptual view is that the “Queenslander” conflates the scale and imagery of both “palace” and “cottage” in a simultaneous co-existence of bipolar opposites.

This interaction between “fringe” and “core”, as well as the double scale, is a recurring aspect in our work – for example, the Mt Nebo House, Oceanview House and Mooloomba House. Aldo van Eyck introduced a further variation with his idea of form and counter-form, which he demonstrated with the example of the mollusc and its shell.

Although these are in most respects “opposites”, they have what he called a relationship of reciprocity.

The consequence for architecture is that we may consider the form, and look for a balanced co-existence by including its counter-form. It is in the interaction or reciprocity that the fit is made to resolve the tension between opposites. In architecture this adds meaning to the “in between” or places at the transition such as the window, door, portico and framed opening that mediate between the contrasting realms of inside and outside.

The pleasure of being in a sheltered place is first experienced in childhood play (getting under a table or into a cubby house). John Summerson reminds us that the relationship formed between the child and the miniature shelter offers delight and a serene pleasure that endures in adult life. He writes that in camping and sailing, for example, “there is the fascination of the miniature shelter which excludes the elements by only a narrow margin and intensifies the sense of security in a hostile world”.

These two states of being – either sheltered within the secure interior or exposed on the hostile exterior – are spatial opposites and the transition between the two brings with it emotional tension. Tension is at its greatest at the threshold between inside and outside and this creates a third place distinct from the others. This tension can be reduced by the polarities being resolved either to coexist in a balanced relationship or by amplification as a moment of drama and reorientation.

Architecture is concerned with practical issues and by necessity it is also assertive.

For example, it orders the patterns of use in a place. If, however, the experience of a building is limited to pragmatics, then memory and imagination are not engaged and relationships beyond the utilitarian tend to be limited. When “use” is balanced by an empathic consideration for experience, this same assertiveness can be pleasurable.

Architecture’s additional role of enhancing the “spirit of the occasion”, or the qualities of a place, contributes to the much larger idea that a building can orchestrate settings for interactions between people. Sequences of arriving and departing, of greeting and farewelling guests, for example, are recurring, often complex social rituals that can be mediated by design. The simple human response of “pleasure in the use of buildings” signals a fit with the needs of everyday life.

Architecture acquires a poetic dimension when it considers the appetite of the senses and when a building is experienced through the act of use as an enhancer of the way of life. The expression of egalitarian space is a basic characteristic of modernity, and contemporary materials such as steel and glass afford greater opportunity for transparency and connectivity between inside and outside. This increasing potential for transparency brings with it the need to preserve the primary qualities of the interior as a reparative space that also has the potential to resolve architectural dichotomy.

The subtropical climate of south-east Queensland invites a certain play with layers between inside and outside. Light and shadow are basic conditions that can trigger memories such as sitting under a tree looking out from deep, cool shade onto sunlit grass. There is an opportunity to layer gradations of light and to recall experience through transparency. Full transparency includes the movement of air, sound, light, sight and so on, and involves movement of the sensing body. Partial transparency, such as that offered by a glass curtain, may involve sight and light only. Transparency also offers an opportunity to superimpose dissimilar formal intentions.

In our work, transparency occurs as part of the interplay between the skeletal form of the timber frame and ideas about reciprocity. Christian Norberg-Schultz describes how the timber post becomes an extension of the energy of the timber frame, whereas the stone column reflects static resistance to the forces of gravity. The exposed, skeletal frame carries a unique architectural expression, a visual dynamic that has a quality distinct from other construction systems. The parts find a logical and dynamic relationship with other members in overlapping systems. This means they are simultaneously individual elements and parts of the whole.

The double reading of the parts and their relationship is a dynamic that is also fundamental to nature and art. The visual dynamic of the three-dimensional timber frame suggests that bio-morphic metaphors – including spines, ribs and cages – are a fertile source of architectural ideas concerning physical structure and aesthetic goals.

Inherent in the exposed frame is the opportunity to express a range of architectural scales and proportions through its subdivision.

In our work we express human presence in the larger form through a geometric subdivision measured to the body and we include scale relations with significant surroundings. So often in contemporary building and architecture the emphasis is |placed on surface, shape and visual abstraction alone. Yet, as the ancients could tell us, the two conditions of skin and skeleton are not at odds. It is within the power of architecture to bring these together and to celebrate their unity.

The various ideas and working principles sketched out above include references to construction, form, use, space, landscape and other common factors in the architectural project. Each has great potential to contribute to an interacting architecture that acknowledges human occupation and experience of continuity in the world.

What Peter and I referred to as the dilemma of Modernism stems from the processes of unfettered abstraction that led to reductive solutions and self-referential buildings. By seeking a more comprehensive view of the architectural proposition, by understanding architecture’s role as a form of reconciliation, and by engaging in poetic abstraction as well as the pragmatic, the potential of abstraction may be harnessed to investigate the “uncut” problem. With the loss of innocence and sense of fragmentation that mark the end of the twentieth century, we recognised that this is not just an option for designers, it becomes a responsibility.

References

- Ann Cline, A Hut of One’s Own: Life Outside the Circle of Architecture (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1997) pp. 27–37.

- William J.R. Curtis Le Corbusier: Ideas and Forms (Oxford: Phaidon, 1986) p. 42.

- Adrian Stokes, “Colour and Form”, and “Inside Out” in The Critical Writings of Adrian Stokes, vol. 2 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1979) pp. 75, 172, 179.

- Colin St John Wilson, Architectural Reflections: Studies in Philosophy and the Practice of Architecture (Oxford: Butterworth Architecture, 1992) pp. 4, 31.

- Francis Strauven, “The Urban Conjugation of Functionalist Architecture” in H. Hertzberger, A. van Roijen-Wortmann, F. Strauven, Aldo van Eyck (Amsterdam: Stichting Wonen, 1982) pp. 96-116.

- John Summerson, “Heavenly Mansions: An Interpretation of Gothic”, in Heavenly Mansions and Other Essays on Architecture (New York: Norton Library, 1963) p. 2.

- Christian Norberg-Schultz, “Treverk”, in Arkitekturhefte 1: Arne Henriksen Prosjekter (Oslo-Bergen: Trelastindustriens Landsforening, 1998) p. 3.

This is a shortened version of Brit Andresen’s A. S. Hook Address, given on October 24, 2002.

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jan 2003

Words:

Brit Andresen

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2003