Photography by Robert Frith

Review

The eastern permeable facade of the Consulate General’s Residence, facing Claisebrook Inlet.

The Consular Office building and gatehouse seen across Brown Street.

Looking west between the Consular Office building, left, and the gatehouse to the Chinese flag in the centre of the lawn. The Perth CBD skyline is beyond.

View through the Function Hall and courtyard to Claisebrook Inlet.

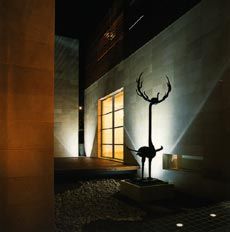

The entry courtyard to the Consul General’s Residence, with a traditional Chinese welcoming figure.

Looking west along the inlet walk into the Function Hall with the residence in the foreground.

The layered facade of the staff accommodation block facing Plain Street.

Looking from the Consul General’s balcony, through timber screens, to Claisebrook Inlet.

The ceremonial stair leading from the foyer up to the Consul General’s Residence.

Looking across the inlet to the chancellery complex, with the fabric of East Perth in the background. The Consul General’s Residence in the foreground, with staff accommodation, left, and the Consular Office building, right, beyond.

An architect friend recently urged me to take a look at the newly completed Chinese chancellery complex in East Perth, designed by Spowers. Over the phone, he described a somewhat bewildering scene: red flag flopping in front of a “Spanish Rationalist” building. But my informant could not help commenting on some “not-quite-rational” roof gestures within the same complex.

My curiosity was aroused: what is left for a building if it is free from the burden of overt representation – of nationality or cultural identity in this case? My visit to the chancellery coincided with that of renowned Beijing architect Yung Ho Chang. After being lost several times along the contorted Brown Street – broken, I presume, by the East Perth inner city redevelopment – we finally parked our car without realising that the building was in fact just on the other side of the road. Yung Ho then saw the red flag, and our eyes moved on to the building complex beyond. Despite its predominantly flat-roofed forms, the yellowish stone-clad surface certainly helped to merge the complex into the newly developed “sandstone-and-red-tile” East Perth – an instant new urbanism. After walking around the complex, we agreed that it was a Chinese dayuan – a big compound or courtyard. Our memories of communal institution living in China enabled Yung Ho and me to see the complex in this way. The chancellery, like an institution in China, accommodates working, living and entertaining. The dayuan in China began to be corrupted in the 1980s, but the memory of such communal living is still vivid. Indeed, Yung Ho’s own contemporary reading of the urban fabric in Beijing centres around dayuan. His architecture aspires to retain and enhance a Chinese spatial experience – an embodiment of a living memory.

A second visit to the complex with the architects convinced me that the chancellery is just a partial dayuan, and that this is a legacy of Chinese communal institutions, brought to the project by the client. It is, however, a truthful and yet skilful embodiment of the current Chinese institutional structure and culture. Chinese diplomats are still required to work and live together in the same complex, although a “collective consumption of food”, requiring a big communal kitchen plus a dining hall, is no longer necessary (all Chinese institutions used to have communal kitchens, abroad or not).

The chancellery complex, in fact, is not a dayuan as such; it is not an introverted fortress with a courtyard in the middle, although many embassy and chancellery buildings are fortified in one way or another. The complex consists of three linear buildings – consular office building, staff apartment and consul-general residence – located perpendicular to each other in another linear fashion. The dayuan, thus, is notional and is carefully crafted in the hands of the architects. A courtyard is an enclosed outdoor space which serves a building, not the street or larger urban space beyond the building. In other words, a courtyard is a private outdoor space. In the case of the chancellery, three different buildings are wedded together with a series of outdoor spaces – fenced gardens and enclosed sculpture courts – in order to materialise the concept of dayuan. As a result, the complex as a whole is physically separate from the public realm.

Accessibility in the Chinese Chancellery complex is a two-way visual exchange.

From the inside, there are “borrowed views” (city skylines) and vistas (inlet and the river beyond); from the outside, the building envelopes are carefully corrupted to reveal sculpture objects and gallery corridors. The “real” building fabric is in fact recessed behind these courts, sealed with artwork grilles, louvered balconies and fenced gardens, which serve as a layered security buffer zone. Although physical public access to the building proper is not possible at the inlet edge, this visual accessibility is a shrewd architectural strategy to achieve an integrated urban fabric along the river inlet pedestrian walk. Such visual permeability suggests a generous public urbanity. As Joseph Rykwert observes, New York corporate buildings, for example, were more accessible in the early 20th century when American dreams could still be dreamed by everyone in the street.

It would not be too hard to imagine another kind of “integration” in this East Perth context where bastardized building styles (Tuscan, Georgian or Federation, just to mention a few) are already used to fabricate an “urbanity” – pagoda roofs perhaps?

Instead, the architects have achieved a careful spatial integration through a negotiation between the two parties – the client representative (a young architectural graduate from Beijing, who happens to have a sober taste) and the East Perth planning authorities, (who wanted the complex to be “contextualised”). The architects, working with humility, skills and imagination, managed to reach a “fit”. It is an accidental bonus if the framed views, or the visual exchanges, also invoke the spatial experience of a classic Chinese garden.

The building, then, is a “nice fit” to the institution that it accommodates, as well as to the place in which it is sited. This “fit” suggests the analogy of the architect as tailor, or as craftsperson. This analogy may seem rather passé, but it is worth reconsidering. To be a good “tailor” architect, first one must be determined to reveal the existing reality or human situation; second, one must possess skills. However, the “tailor’s position” of sincerity and humility has been difficult, if not impossible, since the turn of the 20th century. For most of last century, artistic and architectural endeavour was predicated on the idea of the avant-garde, where newness became the only measure of art, rather than a pursuit of craft virtuosity. But, while artists and architects were busy with their revolutionary inventions, anthropologists quietly went into the “field” to examine preindustrial and non-literate societies. One of their “discoveries” was that, in addition to imitating the universe, buildings actually imitate their inhabitants. A house, for example, is like its occupier, or is at least a second skin for its inhabitant – a nice fit, we might say.

In the case of the Chinese chancellery, this tailoring required firstly an understanding and an acknowledgement of its institutional culture and its site, and secondly the will and ability to materialize it through skillful spatial dispositions. But architecture should be more than a “nice fit”. It should also enshrine the fears, the hopes and the imaginations of the inhabitants. In the Chancellery complex, the architects have made a series of “suggestions” that move beyond a Chinese institutional culture. A backyard BBQ and lap pool, although slightly exotic for a Chinese diplomat, are legible and happily embraced. Other suggestions are more subtle and require efforts from the inhabitants to make them legible: a “grand stair” connecting the Consul- General’s residence and the reception celebrates the ceremonial roles of the Consul- General and spouse at functions; the louvered windows, terraces and balconies suggest that the inhabitants should “let the breeze in” at certain moments. I sensed a slight uneasiness about opening up the louvered terrace from Mrs Consul-General when she showed me her new residence. But I am sure this is not a resistance; rather it is an anxiety in the face of a suggested new lifestyle. On the other hand, the gatehouse in front of the Consular Office building, though symbolic, affords a familiarity to its Chinese inhabitants, but perhaps it is an “exotic” addition, along with the red flag, to the urban renewal in East Perth.

There is no doubt that the complex, as it stands, is a result of negotiations between the clients, architects and the city planning authorities. But, like any building, it relies on the skills of the architects to make it work; it also relies on the architects’, as well as the inhabitants’, imaginations to become legible, which is the very secret of any great building. The architect alone does not give a character, or a life, to a building. As inhabitants, we often get what we deserve.

Xing Ruan is associate professor of architecture at Curtin University

Project credits

The Consulate General of the People’s Republic of China, Perth

Architect Spowers—project leader Dirk Collins; project architect David Hunt; project team Peter Skinner, Kym Muir, Lea Molina, Paul O’Reilly, Ray Skerratt, Foong Lee, John Dalli; interiors Natalie Newton, Yvonne McGuiness. Structural Engineers Barwood Parker. Mechanical Engineers Geoff Hesford Engineering. Electrical Engineers CCD Australia. Hydraulic Consultants Oma Design Services. Landscape Architects EPCAD. Quantity Surveyor Ralph & Beattie Bosworth. Environmental Engineers Gabriels Environmental Design. Builder BGC Construction. Artists Kevin Draper (decorative gates), Elizabeth Mavrick (fused glass).