Looking along the south-west axis to the Griffins’ Newman College, with the Dining Hall in the centre. Image: John Gollings

Edmond and Corrigan’s new Academic Centre, with the Chapel in the foreground. In its broad massing the centre answers the Dining Hall, while its siting reinforces the college’s south-west axis. Image: John Gollings

The Dining Hall at Newman College. Image: John Gollings

The Dining Hall at Newman College. Image: John Gollings

The vertical space at the core of the Academic Centre, seen from the mezzanine reading room. Image: John Gollings

Entrance facade. The splaying porch responds to the congregated spires of the Dining Hall and the rows of pinnacles around the Griffin dormitories. Image: John Gollings

The vertical space of the choral and tutorial room. From inside one looks out to the tall, stylized Gothic Chapel. Image: John Gollings

The student lounge. Image: John Gollings

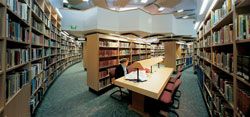

Looking across the library’s main reading room with its fixed shelving. The zigzag edge of the mezzanine reading space is seen above. Image: John Gollings

Looking over the main reading room from the mezzanine. Image: John Gollings

The building addresses a diverse context with great intensity. Split view from the mezzanine over the university sports grounds and the library reading room. Image: John Gollings

The main stair seen in the first floor foyer. The doors to the library are seen to the left and the stair to the sub basement to the right. Image: John Gollings

Stair detail. Image: John Gollings

Looking up through the polygonal central void. Image: John Gollings

This building has a library at its core, surrounded by tutorial and music rooms, a lounge and a long balcony. In both its function and its representation it is a link between the two Catholic Colleges at the University of Melbourne, Newman and St Mary’s. In its broad massing the new centre answers the proportions and bulk of Newman College’s Dining Hall and its spired dome, designed by Walter and Marion Mahony Griffin between 1916 and 1918. Thus it reinforces a diagonal axis hall running south-west from the Dining Hall. When seen from Carr, Newman’s original north dormitory, and from the Dining Hall’s courtyard front, the centre’s faceted edge and subdued colour make it read as almost not there. It is unobtrusive even from Mannix, the much closer east dormitory. Seen from this angle, the two large gum trees in front register and reflect light more strongly, and the cement render on the new building links it to the neighbouring Donovan and Kenny dormitories, built to others’ designs in 1954 and 1958. This allows the centre, in turn, to work as a subdued backdrop to the Chapel when seen front-on from Swanston Street: its colour values and roof line matching the backdrop given by the Donovan wing on the Chapel’s north side.

In morning light the new centre picks up sunlight and the slowing shadow of the trees in front, but again is more subdued in this light reflection than the Chapel or, for that matter, the original wings of Newman College itself. The centre’s modulation in light reflects a contextual placement in the hierarchy of Newman’s and the surrounding buildings’ context. It is intended as a far more forceful collegiate presence than Peter Elliott’s 1994 Principal’s House behind it – the best building in the St Mary’s College complex. The centre also bears a far greater expressive and symbolic weight than the Murphy flats to its immediate north, a Newman College addition of the early 1970s.

At the same time, the centre works in concert with the rear extensions of St Mary’s College. This is no mean feat as St Mary’s earlier buildings, from 1964 into the early 1970s, are hardly monumental either in solidity or concentrated meaning.

Up closer to the centre you can see any number of Griffin details gathering: terracotta trim on ridges and similar colouration of the decking roofs. A porch splays out like a crown, answering both the congregated spires on the Dining Hall and the rows of pinnacles around the Griffin dormitories. In the same way, the angled entry areas and walling takes up the Griffins’ theme of the angled pier, a crucial motif in their initial college buildings and a way in which they expressed both growth in the rock and their buildings’ correspondence with the trees as planned.

Moving closer still, you can see how the new building physically addresses its eastern contexts by drawing through one visual link after another. There is the duality of the entry, with facets that read equally, if asymmetrically, toward both Newman and St Mary’s. The diamond pattern windows on the upper levels answer the diamond and chevron traceries and vents in Newman and its later wings and the window vents in the Chapel vestries. You see the reason why the centre reads from Swanston Street as a screening backdrop behind the Chapel and from the Dining Hall as receding behind the trees. Its plan is in irregular, zigzagging facets, advancing and retreating by turns, from a podium that reads, alternately, as solid and void. The “solid” side is most visible at the St Mary’s end, the hovering side at the Newman end. Up close the building is the embodiment of tumult and movement, but in its contextual frames it presents specific episodes, with great precision for the job each has to do. This combination resembles the pylons and bridge supporting Edmond and Corrigan’s Building 8 at RMIT, but it is structurally asymmetrical here. In a sense the centre goes one stage further, because it is truer in its expression of vertical circulation and of programmatic springing points inside. This can be seen in the charge desk and librarians’ rooms, from where the library space literally sweeps out. This sense of drive outward – in facets from a collective trunk of circulation and gathering spaces – recalls Frederick Romberg’s combination of mass and projection at Stanhill, 1943–51, and the Stuttgart apartments of Hans Scharoun – both of whom have interested Corrigan for decades. The plan’s cranked, “armadillo” aspect to the south-east, where tutorial, seminar and music rooms splay out in freed trapezoids, also recalls Corrigan’s early Trinder house project for Corio, of 1965. This house carryover is appropriate enough. Alex Selenitsch, taking larger Edmond and Corrigan houses such as Calnin or McCartney as examples, has argued that the internal politics and coexistences of a house give it an institutional demeanour like any other building. The sheer verticality of the new centre is initially startling, though – given that earlier buildings by Edmond and Corrigan, Keysborough in particular, were emphatically horizontal. Arguably, this reflects the centre’s origins in sketches for a clustered tower, and it also allows the centre to read as light and hovering, or heavy and bearing down, when viewed from one compositional bay or episode to the next.

This heightens the sense of the building’s physique, in turn complementing the sense of facial or anthropomorphic expression that has always been present, even in the placement and detailing of a single Edmond and Corrigan window.

In plan, the central library is ringed at each level by tutorial, music and service rooms, offices, a lounge and even an eyrie “poet’s room”. This repeats the Griffins’ clustering of anterooms, Lady Chapel, rector’s and priests’ rooms and service areas in a democratic circle round the 1918 dining room. The new plan’s generation, however, is quite different, as it emerges from a gomon -like concept plan with stubby arms and concentric spatial organization. The gomon plan – in concept and in final form – was a natural conversion of the early sketches. In the design’s evolution, the building turned from being a refuge-library to giving image to the community life of students around and inside the library. Externally the centre, as you read it by episode, remains in part a refuge tower, a moat and bailey, from the west and at a distance from the Chapel side approach. But suddenly the form breaks open on the north and north-east, showing its internal life and the whirl of student movement envisaged for it. A balcony spins out from the student lounge, sweeping round over the car park, cutting through the general sense of mass, before changing into the complex essay that is the western escape stair. Here again this is something that can be seen at Edmond and Corrigan’s Drama Centre for the Victorian College of the Arts, finished in early 2003. There the building literally invited the student community onto its external decking, with chairs and drinks hauled out, in both a promenade and a serried watching of the collegiate spectacle outside. In doing likewise, the Academic Centre returns to the early grandstand and sports pavilion forms of Keysborough, Box Hill and Sale, and to the image of the populated building whose users become participants – not just in the architecture as spatial experience but in the architectural form itself.

The library is double-height, with the upper level bisected by a zigzag-edged reading space that works like a bridge. It closes the circle of a polygonal upper space over the charge desk and reference section, which resembles the Dining Hall dome and its looping sequence of solid-walled balconies. The reading room has a similarly teeming feel, and this is heightened by Edmond and Corrigan’s placement of fixed library shelves, which act as island solids through which space flows. The sense is rather like that of H. H. Richardson’s spatiality, though the sense of a landscape of books, and of the white, air-like spaces above, is a synthesis of Asplund’s classicism at the Stockholm library, and Aalto’s internal terrain – as at the Wolfsburg library. It also extends Edmond and Corrigan’s use of fixed timber library furniture, in creating both a sense of occasion and richness. This can be seen in RMIT’s Central Library at the point where the repeated stacks of its older Casey Wing precinct run through into Edmond and Corrigan’s Building 8.

In the new centre the librarians had to arrange the two colleges’ combined collection: between 80,000 and 110,000 books (no-one knows the exact figure).

The planned juxtapositions of disciplines bring students from different disciplines into contact: theology is across a narrow aisle from economics. Corporate law is next to poetry. Medicine is next to art and architecture. The main computer room looks in on this reading room, literally, projecting out into it with a glass bay. Visually linked to the library, it is still kept separate from the library’s spatial role as a store of printed books – everyone was determined this library was not going to become just a contemporary information retrieval depot. The computer space is unusual in itself, having a tall ceiling that is familiar from older university buildings, but which is unexpected in the minimal spaces of modern computer labs. Indeed this vertical generosity, grand and solemn at once, is part of the centre’s verticality and stems from the early concepts of a library-tower. This verticality gives the reading room its sense of occasion – so rare in modern libraries, generally impoverished by their technocratic expression of volumetric efficiency. The same is true of the two flanking choir and ensemble rooms which, inside, link visually with the tall, stylized Gothic of the Chapel through the windows. The main lounge, similarly tall, seems to acknowledge the flow, visual and implied, of student life through the room and out onto the long balcony.

Even here we are reminded of the sheer diversity of the context and of the intensity with which this building addresses it. Not only are the Griffins referred to; so too is W. B.

Connolly, with Payne and Dale in the 1939 Chapel. St Mary’s College, opened in 1964, is in almost a designer-builder’s vernacular with a Baroque “hop” over the front door. It left no room for the Griffins’ idea of a mirror-image of Newman as completed. In their original design the library and its surrounding tutorial rooms were to be housed in a dome externally matched to the Dining Hall. In a sense the new centre recalls that unbuilt dome but expresses context as a wider and more complex mix. Part of the centre’s sheer force on its north and west elevations is a response to the visual force of its neighbours: the bulk of the gymnasium, c. 1970–94; the heavy-scaled towers of Protestant colleges to the north and west; the university’s central campus as a cream brick forest of tower-slabs; and the convergent theatre of the central sports arena. All this is taken on board, and yet reconciled with the difficult plurality of the Centre’s proposed interior life, expressed in the way its spaces and forms are shaped. For the Centre has about it that sense of an expanded community dwelling, where students can literally circulate, moving round the library level to talk to or make contact with friends.

As the manager observes, the action of library discussion can flow out easily into flanking tutorial rooms. The ring of tutorial and music rooms on the fourth floor, smaller like attic spaces, can buzz constantly – spatially linked yet acoustically protected from the library immediately through the central void below.

Designing this centre brought particular difficulties. Much has been built since the original Newman buildings were constructed, and the Griffins still cast their long shadow. Edmond and Corrigan’s new building rises to this challenge, responding to the original design and the buildings surrounding it and bringing to bear a use of space and flow that is remarkable and new in such a building. All this is directed to a principal aim: that the centre carry in its form the sense and image of community, read from both outside and in, and from a whole series of perspectives.

Credits

- Project

- Academic Centre for Newman College and St Mary's College, University of Melbourne

- Architect

- Edmond and Corrigan

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Peter Corrigan, Maggie Edmond, John Karick, Adrian Page, Raymond Ng, Michael Taylor, Simon LeNepveu, Anna Little, Cyril Yu, Julia Jang, Zlatko Basic, Alan Kueh, Jon Yong

- Consultants

-

Acoustic consultant

Marshall Day Acoustics

Building services consultant Meinhardt

Building surveyor Thomas Nicolas

Disability consultant Morris Walker Consultants

Fire safety engineer Bruce Thomas and Associates

Heritage consultant Bryce Raworth

Landscaping Edaw

Quantity surveyor Westbay Consulting Services

Structural and civil engineer Meinhardt

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Sep 2004

Words:

Conrad Hamann

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2004