The statistics are stark: by 2041, the Greater Sydney region’s population of people over 65 years of age is predicted to reach more than 1.2 million, more than twice as many as there are today.1

Sydney benefits from a wide range of programs to support neighbourhoods and communities adapting to this social shift, including state government strategies and transport plans for seniors, a broad range of efforts led by the not-for-profit and social enterprise sectors (such as The Australian Centre for Social Innovation’s Homeshare, which enables older women to create safe and secure co-living situations), and two local governments (Liverpool and Lane Cove) that have been part of the WHO Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities since 2014. But none of Sydney’s other local governments has joined this international network that is seeking to find appropriate, innovative and evidence- based initiatives for assessing age- friendliness. Does Sydney consistently provide for its older residents? And are the city’s solutions fit to meet the diverse needs of these residents where they live?

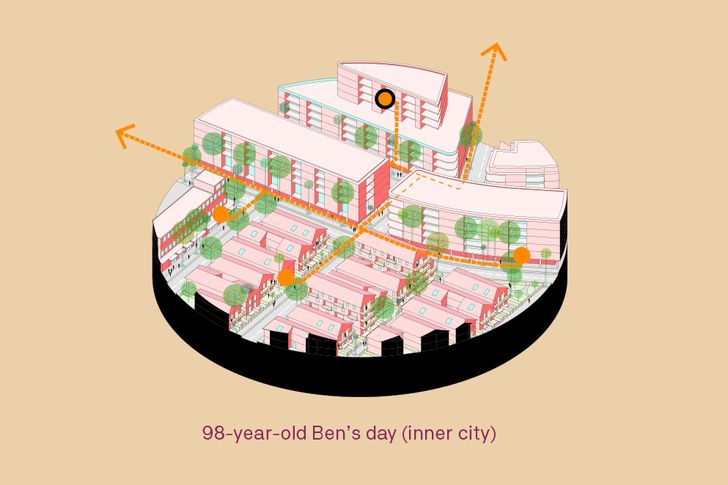

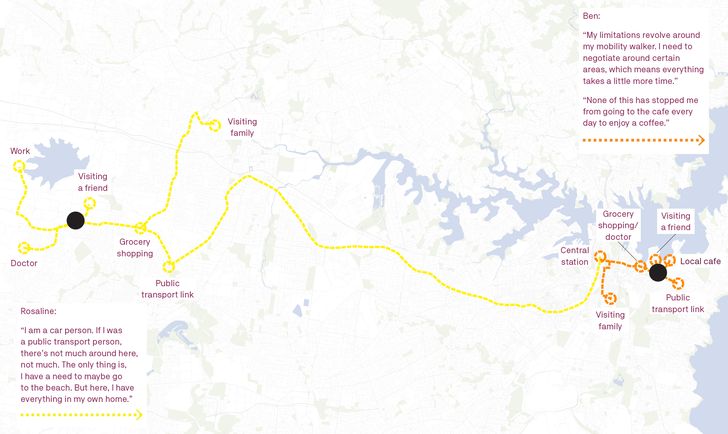

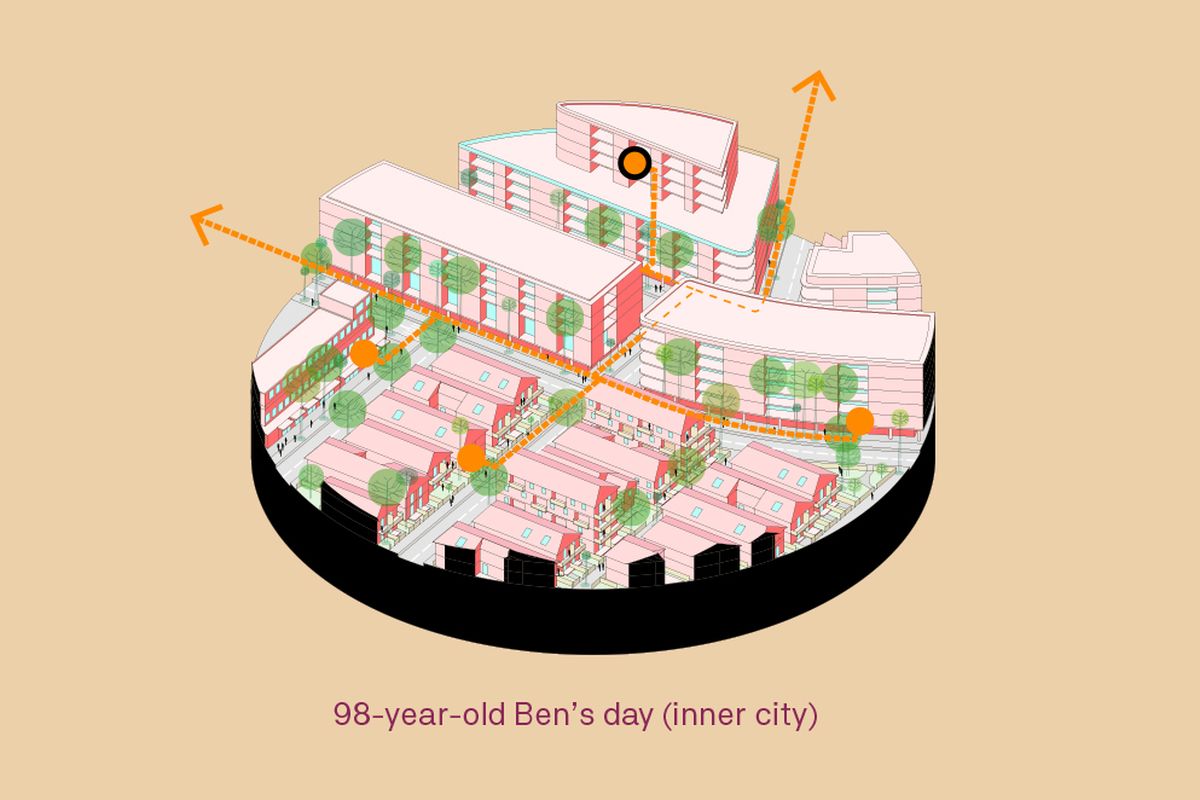

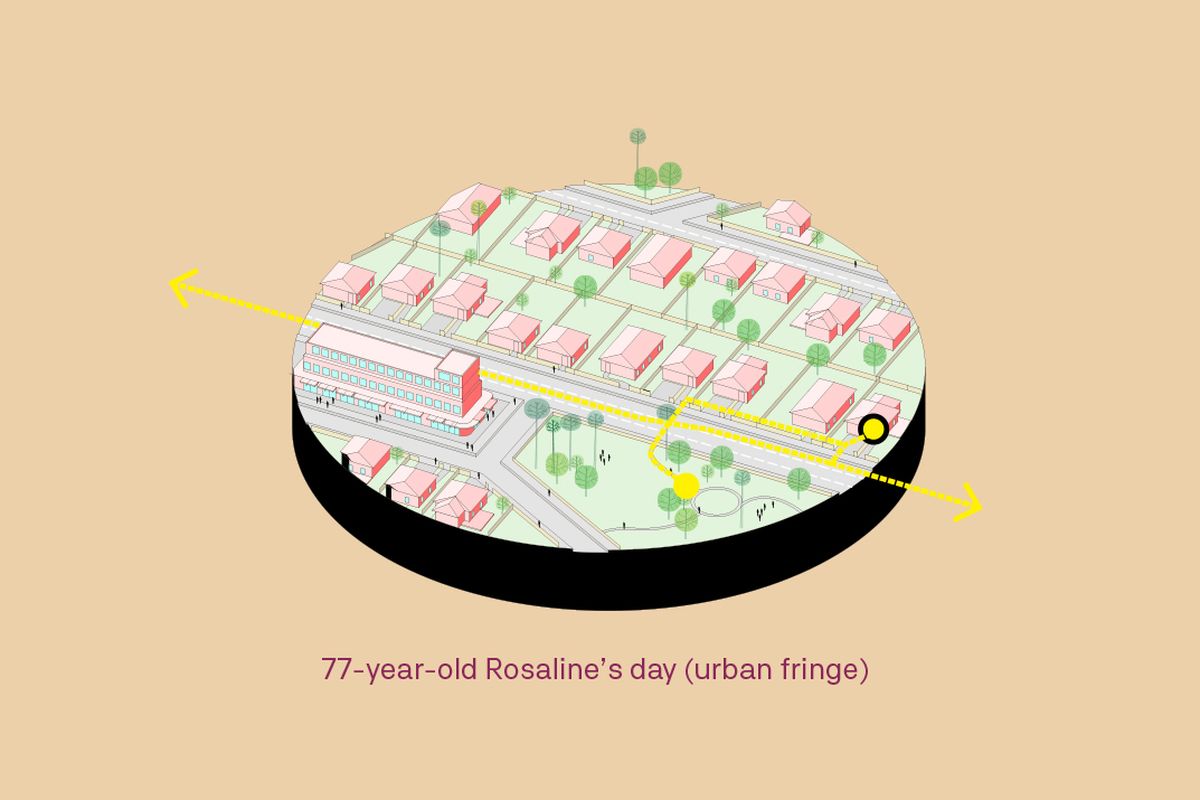

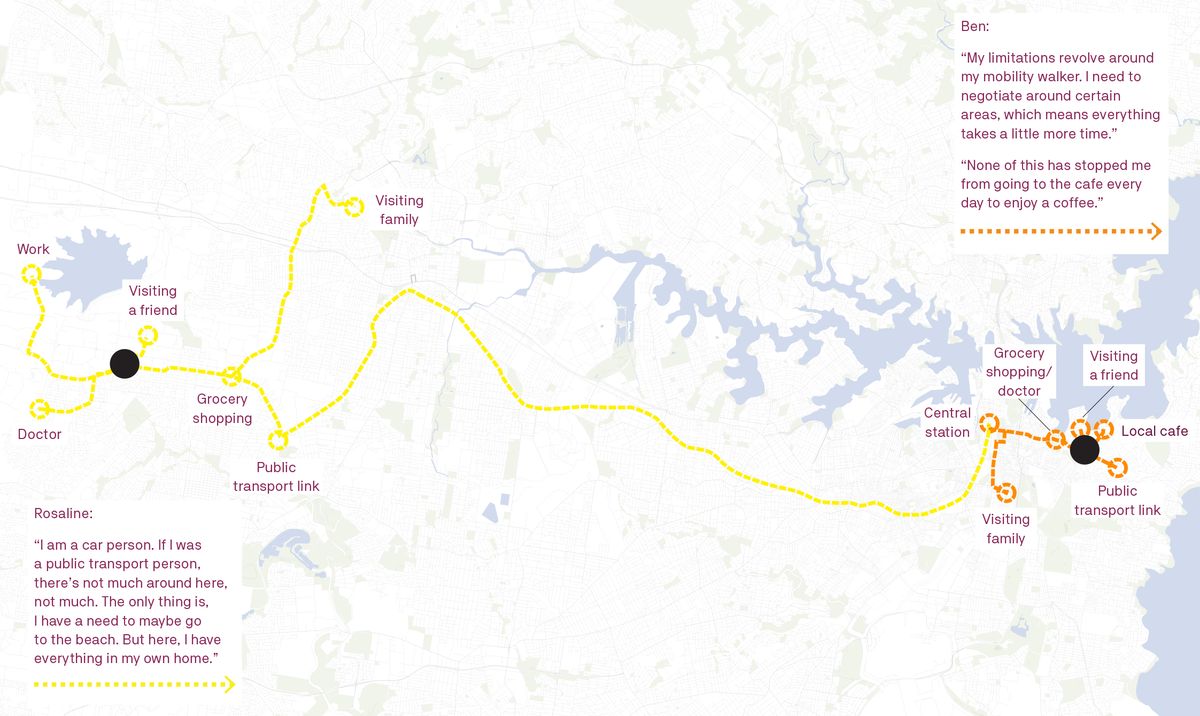

Grimshaw interviewed two older residents living in Sydney in 2021 to compare their perceptions and experiences of how their city caters to their needs.

Image: Daniel Tonnet, Grimshaw

One Sydney local authority proactively preparing for this demographic change is Liverpool City Council, where the number of people aged 65 and over is estimated to increase from 21,600 in 2016 to 68,650 by 2041.2 According to the Mayor of Liverpool Wendy Waller, the council is aware of both the coming change and the importance of “incorporating the existing and future needs of our growing local aged community within Council’s planning and infrastructure development.”

Currently under construction, the mixed-use Liverpool Civic Place development provides an example of the city’s approach to designing with older adults’ agency in mind. Waller emphasizes several significant features of the project, which was designed in response to feedback from older residents. These include drop-off/pick-up zones for people with mobility aids, a hearing loop in the library and meeting rooms, “rest stops” throughout the complex for those with mobility issues, and colour contrast and large fonts on signs and wayfinding.

Grimshaw interviewed two older residents living in Sydney in 2021 to compare their perceptions and experiences of how their city caters to their needs.

Image: Daniel Tonnet, Grimshaw

Through the WHO program, cities such as Liverpool develop strategies and apply actions at the scale of the suburb or local government area. There are, however, other established tools and frameworks that planners, architects and designers can apply on smaller scales, such as precinct masterplans and high streets. One example is a new operational framework for health impact assessment from the Asian Development Bank (ADB). In recognition of the convergence of ageing populations and infectious diseases like COVID-19, the framework aims to integrate public health into planning and design. Although the framework’s initial focus was China, its objectives can be applied to other countries, including Australia. ADB health specialist Najibullah Habib says that the framework calls for “well-planned, decentralized, and conveniently located urban health services ideally within walking distance to many residents and public transport, early detection of infectious diseases, and measures for vulnerable groups such as the elderly [to] help reduce noncommunicable diseases, control infectious diseases, and promote well-being. ”3

The interviewees’ daily journeys were mapped to show what it’s like to age in place and the impacts on their personal mobility.

Image: Daniel Tonnet, Grimshaw

Other holistic tools include age- and dementia-friendly streetscape toolkits, such as the one developed with residents and shopkeepers of Union Road in Melbourne’s Ascot Vale. Through a participatory design process, the street’s redesign was informed by a broad range of evidence that encompassed data and lived experiences, leading to the suggest-ion of relatively simple interventions to improve walkability and prioritize pedestrians in high foot-traffic areas through more seating, better lighting and wayfinding, and increased access to public facilities such as parks, libraries and toilets.4

While frameworks such as these respond to the specific needs of older people in our built environment by taking a mono-generational approach, there has been a recent movement toward concurrently exploring both age- and child-friendly cities. In Sydney’s Northern Beaches, the Harbord Diggers community space combines retirement living, child care and swim facilities in one precinct, demonstrating the benefits of bringing together services and infrastruc-ture that address the needs of both groups.

Gunyama Park Aquatic and Recreation Centre (GPARC) designed by Andrew Burges Architects, Grimshaw and TCL.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Another example is the recently constructed Gunyama Park Aquatic and Recreation Centre (GPARC). Designed by Andrew Burges Architects, Grimshaw and TCL, it is located within Sydney’s Green Square town centre, one of the largest urban regeneration sites in Australia. GPARC provides opportunities for intergenerational connectivity through both planned and informal interactions. Design director Andrew Burges says, “Our response to the brief was to be expansive in the range of community functions it provides to accommodate a much broader community.” Burges also describes the reconceptualization of a traditional pool to “a more freeform geometry that provides unprogrammed water spaces for play and relaxation as well as more active lap swimming, accommodating the many different social scenarios, abilities and ages required at a public pool.”

Clearly, designers have a critical role to play in delivering on agendas to best support ageing in place – which is something that 78 to 81 percent of Australians aged over 55 want to do.5 The shared experience of COVID-19 has highlighted the importance of involving the community in co-producing design solutions and the speed with which designers can adapt the built environment to specific needs. Now, designers have an opportunity to respond to the demographic change that is already underway, to build on the momentum of co-production to pilot more age-friendly solutions with o l der residents, and to integrate public health imperatives. The examples discussed here demonstrate the significance of each step of the design process, from developing the brief to evaluating the impact of the design, in facilitating Sydney’s progress toward a more equitable and liveable city.

1. NSW Government, Department of Planning, Industry and Environment, 2019 NSW Population Projections, planning.nsw.gov.au/Research-and- Demography/Population-projections/Projections (accessed 25 June 2021).

2. NSW Government, Liverpool City Council: 2019 NSW Population Projections, planning.nsw.gov.au/-/media/ Files/DPE/Factsheets-and-faqs/Research-and-demography/Population-projections/2019- Liverpool.pdf (accessed 29 July 2021).

3. Pima O. Arizala-Bagamasbad, “How to have healthy and age-friendly cities in the People’s Republic of China”, Asian Development Bank, 23 February 2021, adb.org/news/ features/healthy-age-friendly-cities-china (accessed 20 June 2021).

4. Architects Johannsen and Associates, Age ’n’ dem: Age and Dementia Friendly Streetscapes Toolkit (City of Moonee Valley, 2016), universaldesignaustralia.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Age-Dementia-friendly-spaces-MVCC-Report-final.pdf (accessed 29 July 2021).

5. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), “What’s needed to make ‘ageing in place’ work for older Australians?” 10 December 2019, ahuri.edu.au/research/ahuri-briefs/whats-needed-to-make-ageing-in-place-work-for-older-australians (accessed 29 July 2021).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 7 Dec 2021

Words:

Georgia Vitale

Images:

Daniel Tonnet, Grimshaw,

FJMT,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2021