Review Dianne Peacock

Photography John Gollings

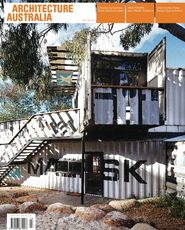

The striking west facade of Albury’s “new lounge room”.

The double-height foyer. “Highway” black ceiling bands flow across and down to drop cabling into the library.

Looking along the colonnade on the main facade, with its Miesian columns, from inside the entry.

Museum exhibition space.

The sloping concrete walls and deep fascia of the Swift Street elevation reference both Enrico Taglietti’s St Kilda Library and local tree-lined levee banks.

The dramatic X-forms of the Kiewa Street elevation might be read as Roman numerals or as the truss of a steel rail bridge crossing the Murray River.

The south-western corner.

Detail of the southern elevation.

Public space on the Swift/Kiewa Street corner. The plan of the glazed facade follows the line of the river.

The bold green wall of the cafe area, which will help address Queen Elizabeth II Square as the precinct evolves.

LibraryMuseum is a composite word from Albury. The name of the city’s new lounge room, by Ashton Raggatt McDougall, it refers to a combination that has so far proved to be a productive and popular initiative by Albury City.

ARM is known for detailed expositions of its methodology, techniques and sources. While past work includes the St Kilda Library extension, Marion Cultural Centre and National Museum of Australia, the methodology used in this project and others is not based on building typology (although there is an interest in the civic institution). The architects study local conditions and pursue the re-emergence, in their architecture, of local forms and architectural references, obvious and obscure. As described and argued elsewhere, architectural investigations of the relationship between the original and its copies are made in this process.¹ Methodology is repeated and renewed in each project.

Roadkill: the architects drive around and photograph the city, searching for what the road might throw up. Found objects are presented back to the community as roadkill. While this is a simplification, roadkill is their term. As a method it involves searching and finding, the application of experimental and sophisticated techniques of transformation, and sensitivity to the conditions of the regional city.

ARM’s Roadkill collection of objects supports engaged community ownership of the project through the dialogue and speculation generated around its language and meanings. Albury’s place on the Murray River and state border is used in naming the museum’s permanent exhibition, Crossing Place. This conveys stories of the Wiradjuri, the Bonegilla Migrant Reception Centre and many others – and includes the fact that Albury is the birthplace of Maggie Kirkpatrick, known for her television role as Joan “The Freak” Ferguson in Prisoner. Uncanny correspondence occurs between ARM’s collection of Albury parts and the contents of the museum’s cabinets, where the obscure brushes up against the obvious. Crossing Place has the whiff of roadkill – in the best possible sense – dangerous, chanced upon and potentially nourishing for some. The Flying Fruit Fly Circus photographed by Anne Zahalka and Gerhard Ziermann’s 1981 monumental matchstick art rendition of Hume Dam Wall are on display. The Murray River is the museum’s unifying theme and is said to have generated the line of the building’s glazed facade and forecourt landscaping.

Being concerned with objects and the information they convey, libraries and museums might appear to be natural neighbours. In contrast to the nineteenth-century model of the civic library, the municipal museum emerged here in the 1970s, with the former Albury Regional Museum opening in 1983. Albury City’s development of the LibraryMuseum project is credited as a catalyst for new organizational structures. Now, instead of separate departments, a cultural management team oversees all that is cultural and collected in Albury City – a scope that includes civic architecture, municipal records and the work of curators and librarians.

The library and museum converge in a double-height volume between the main entry and staircase. An accessible balcony affords a view (and a sense of ownership) over the library and foyer. Its white ceiling rises from the northern end of the library, carrying with it a series of strong black bands marked with the dashed lines of fluorescent tubes, a suggestive image for those who have driven the Hume Highway at night. These bands also drop cabling down to the library and work areas. The Infozone located at the elbow of the building houses programs and objects common to both library and museum: technology, public work space, drawers holding historic maps, etc.

The LibraryMuseum is sited at the corner of an established civic precinct currently undergoing renewal. It is intended to address a civic plaza and Queen Elizabeth II Square as the precinct evolves. Council was determined to promote public ownership and use of the LibraryMuseum and directed efforts and investment to the public areas of the complex. The back-of-house area is modest and storage is mostly off-site. It is a public building with a public role and presence, but one where parents seem relaxed about letting children wander from books to exhibitions to computers. This new type of community lounge room (this is the council’s term) has three potential public entrances. The main entrance faces a street corner. A tall glazed facade is set back from a sequence of black steel columns supporting a lofty veranda, while tracing a gentle path to the main entry. This sequence of columns, roof, mullions and ground plane is beautiful to walk through. The columns are expressively Miesian in their physical, material presence, yet tall, dark and light enough to appear stretched as the roof rises across the elevation. The window mullions are timber, deep in profile and stained black. Mies van der Rohe’s IIT Crown Hall is offered as a reference. When photographed obliquely, as shown in many reference books, its expressed wall framing exhibits a strong and dense verticality. ARM engages here with the tradition of modernism and materiality and, in doing so, recognizes a convergence with other contemporary architecture.

Expansive glazed walls are frequently employed by architects to lend an impression of openness or transparency to what goes on inside corporate and public buildings. Any impression of this often-boring typology is avoided here, despite actual transparency and extensive glass, thanks to the deep mullions, the blackness, a precast, table-height base wall that blocks much of the floor from view (while allowing the internal edge space to be occupied) and the fact that there are other things to see.

The steel fascia is discontinuous, its edge sliced back into itself at major roof junctions. Along the north facade, the slices are deep and wide enough to have produced a sequence of individual roof overhangs (or horizontal castellation). These hover above deep recesses between sloping concrete walls. Trees growing from within these walls reach for the gaps above. The walls, in conjunction with the deep fascia, refer to Enrico Taglietti’s 1973 St Kilda Library and locally to the tree-lined levee banks of a city built next to the river. This poetic synthesis of roadkill and architectural precedent conjures the impression that as the trees grow, the river will increase its presence at the site.

A striking emblematic facade faces a T-intersection on Kiewa Street. The facade is deep and patterned with a series of X forms that appear to contract laterally from left to right. The surfaces of its diamond-shaped recesses are orange-red. Its form comes from the structure of a disused nineteenth-century steel rail bridge crossing the Murray River. The facade’s top and bottom plates assist reading it as a truss (and as an extended Roman numeral). The bridge’s geometry was mapped onto a cylinder and its image then flattened, producing the effect of compression across the facade. Conversely, it is understood as a thick slab from which diamonds have been subtracted, adding to the architect’s series of subtractive volumes.

Floors and roof truncate these diamond-shaped openings internally, with the exception of one complete diamond window located adjacent to the main entry door and on axis with the foyer. Upper-level windows have since been furnished with black shading blinds, rendering these geometries slightly sinister.

ARM’s work is characterized by assembled forms, including text, which may or may not be readily identifiable but are rarely, if ever, reducible to singular readings. The LibraryMuseum employs forms that shift between figure and abstraction. The letter X is a sign that carries many meanings and provides a specific naming function in the museum. X also happens to be a generic structural figure common to architecture in the form of struts, bracing and drawing. The roadkill bridge structure could have been brought into the medium of architecture with minimal adaptation, yet it underwent a high degree of transformation and, while legible, exceeds direct reference. In some respects the steel veranda column is more the found figure here than are the Xs of the facade. Its transformation is subtle, but it is the roadkill that provokes such a reading.

Dianne Peacock is an architect who engages in art practice and is a member of Antarctica.

¹ Michael Markham, “Originality” in Transition 47, 1995, pp.36–45.

ALBURY CULTURAL CENTRE

Architect

Ashton Raggatt McDougall—project team Ian McDougall, Andrew Lillyman, Rhonda Mitchell, William Pritchard, Ross Privitelli, Andrea Wilson, Anthony McPhee.

Landscape architect

Ashton Raggatt McDougall.

Building services

Irwin Consult.

Contractor

Zauner Construction.

Exhibition designer

Banyan Wood.

Client

City of Albury.