Teaching and studying landscape architecture is probably a lifelong commitment – a way of being that ducks and weaves and evolves as a set of slow, reconciled “cosmologies.” The immersion in landscape architecture becomes a way of making sense of oneself, one’s family, one’s community and the world. From my observations, landscape architecture typically attracts certain individuals and collectives driven by the complexities, beauties and uneasiness of its integrated disciplines. These people and groups have far-reaching social and professional goals to creatively imagine, think through, make up, learn from or destroy. They hopefully look after the oscillating temperaments of time, space, place and home (and all its slippery in-between ingredients and events).

The education in and practice of landscape architecture are measures of societal tension and strife and as such they become a set of rehabilitative activities in the social, spiritual or physical realm and a measure of the relationship between one’s world and one’s earth or environment.1 Looking back to the origins of landscape makes for a powerful framework within which to read space and acknowledge place – these moments, as Australian architect Richard Leplastrier would suggest, raise issues of potency, moment, anticipation and preparation in design.

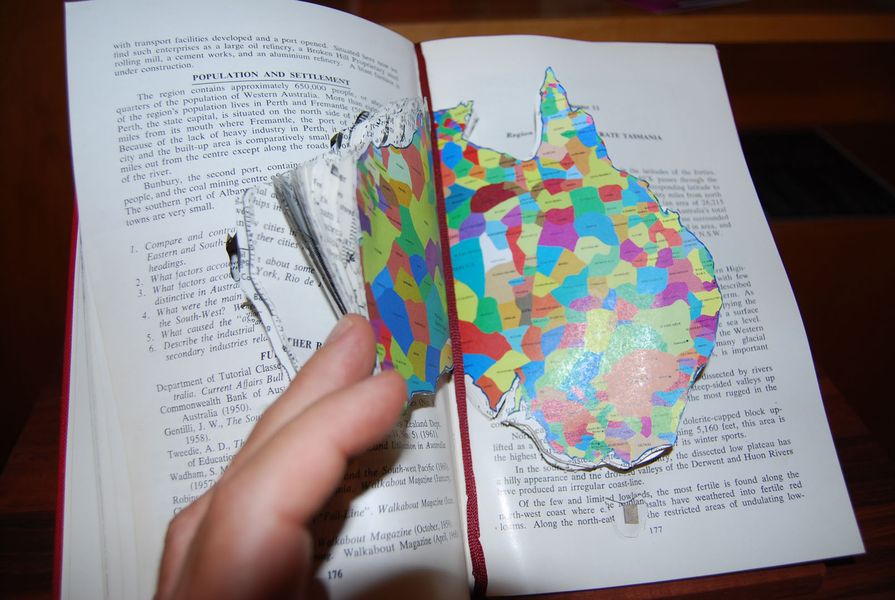

The political wellbeing of a shared landscape architecture showing reciprocity (red), respect (yellow), equality (orange), responsibility (purple), survival & protection (blue), spirit & integrity (green).

Leplastrier talks of the subliminal power of implication over explication; the idea that matters of place suggested are infinitely more potent than those revealed.2 This is akin to landscape being described in terms of entwined (im)materialities and sensibilities within which we might act and sense.3 Similarly, one could adapt the political values of Australia’s health professions, for example, and be guided by a humbling yet potent education that instils an understanding of landscape’s reciprocity (inclusion and benefit); respect (trust, cooperation and dignity); equality (difference, fairness and justice); responsibility (kinship, care and maintenance); survival and protection (collective identity, distinctiveness, solidarity); and spirit and integrity (coherence, continuity and integral behaviours). [See image right]4

Our speculative work at The University of Western Australia (UWA) traverses tricky ground, as architect Melanie Dodd explains so well. Ideas of difference and plurality fit well and where community frictions and chaos are explicit. The work is extremely experimental – more akin to art than design. Students politically avoid “fixing things” and individually or collectively try to aim higher to question and reinvent the social and political aspects of new modes of participatory landscape architecture practice.5

These reconciled metanarratives of an eco-political way of teaching a discipline rather than a paternalistic anthropogenic one are key, I believe, to a contemporary Australian landscape architecture education of deep, lasting worth and respectfulness, as the nation finally embraces and genuinely partners with indigenous Australian culture as at no other time in its history. And it is this reciprocal sense of learning in and being honest with the troubling Australian landscape – its threatened ngurra (country) – that is best told in story. Here I am reminded of many a landscape story shared by my close colleague, Palyku woman Jill Milroy. Jill and I have sustained a collaborative teaching program at UWA for over fifteen years and we seek to openly communicate the friction, chaos and rewards of working in an immature bicultural setting.

Indigenous stories remind us of a landscape architectural education that recognizes that Aboriginal peoples in Australia are the keepers of the oldest story systems and the oldest stories in the world.6 Jill and I research and teach about the importance of stories in understanding and knowing a shared decolonized landscape, and believe that it is through such stories, and their telling moments, that we learn the truth about the world. Stories also teach us that it is not people who are the best storytellers, but that the birds, the animals, the trees, the rocks and the land have the most important stories to tell us. These traditional, handed-down stories exist in real political place, and by being artful or by designing with these story systems we fundamentally alter the way in which we can know country and landscape.

Images 01–03 illustrate some student work from our teaching unit Sharing Space. Here, landscape architecture and architecture students construct 3-D model-essays that interrogate topics concerning designers practising in a proactive shared cultural space. The students’ understanding of decolonized cultural competency and specific shared knowledge of indigenous knowledge systems are critically tested and ultimately presented in public exhibition to the faculty and wider community.

Finally, learning how to collaborate meaningfully with Indigenous storytellers has been a focus of my student teaching. It has been a difficult learning process and one full of new cultural relationships, protocols and finding ethical ways of working inclusively as a landscape architect. It is precisely these provocative intercultural values of a designed, politically-based education that seem to matter to students, and in turn to the offices and agencies they eventually practise in. In Western Australia, the landscape architecture academy continues to deliver on these reconciled frontiers and alternative ways of practice so that politically reformed Indigenous landscape architects and eventual educators will ultimately partner with their informed alumni to create a more just, diverse, inclusive, equitable and accessible Australian landscape.7

I wish to acknowledge the teaching, research and community service partnership I have with Jill Milroy, OA, Dean/Winthrop Professor, School of Indigenous Studies, The University of Western Australia. I also want to thank the office of Urban Design Landscape Architecture (UDLA) for assisting with this essay, Vanessa Margetts and Jeremy Macmath in particular.

1 See: G. Gill, “Landscape and Remembering,” Kerb Journal of Landscape Architecture, no 10, 2001.

2 See: Kristiina Lehtimaki and Petri Neuvonen (eds), Gareth Griffiths, trans., Richard Leplastrier – Spirit of Nature Wood Architecture Award 2004 (Helsinki: Rakennustieto Publishing, 1999).

3 J. Wylie, Landscape (London: Routledge, 2007). I thank Elizabeth Meyer for sharing this landscape critique.

4 I have adapted these six tenets and image 04 from Values and Ethics: Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2003).

5 See: M. Dodd, “Citizen Expert/Expert Citizen: Locating and Valuing Alternate Definitions of Spatial Knowledge” in Melanie Dodd, Fiona Harrison and Esther Charlesworth (eds), Live Projects: Designing with People (Melbourne: RMIT University Press, 2012), 140–152.

6 See: J. Milroy and G. Revell, “Aboriginal Story Systems: Re-Mapping the West, Knowing Country, Sharing Space,” Occasion, vol 5, 2013.

7 For further discussion on the pedagogies and designed outcomes of UWA’s Indigenous Design Studio see G. Revell, “Whatchew Reckon I Reckon?” in Dodd, Harrison and Charlesworth, op. cit., 120–139, as well as UWA’s Rural Design Studio work documented in A. Grieve and G. Revell, “Animated Ecologies – the Slippery and the Curious by Design in N. Duxbury” (ed.), in Animation of Public Space through The Arts: Towards More Sustainable Communities (Coimbra, Portugal: Livraria Almedina & Centro de Estudos Sociais [CES], 2013).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 15 Jan 2014

Words:

Grant Revell

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2013