Architect Andrew Burns is building a portfolio of cultural projects. Having completed the Australia House gallery / atelier in Japan in August 2012, replacing a studio lost in the 2011 earthquake, he is working on another small but symbolically rich building – a temporary pavilion in a Zen Garden. The commission came with winning the inaugural Fugitive Structures competition for the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation (SCAF).

Fugitive Structures is a new four-year competiton whose intentions align with those of London’s Serpentine Gallery Pavilion series, where opportunities are created for pockets of architecture that transcend function and program, though they may be animated through curated exhibits or events. Architecture that transcends function and program is an area of personal interest for Burns, and although his Crescent House design for SCAF will be more akin to a cubby house, size is not reflective of the depth of thought behind it.

Peter Salhani: Australia House and now Crescent House explore the fringes of art and architecture. Is your interest in projects like these theoretical, curatorial, or both?

Andrew Burns takes a break, down the road from Australia House.

Andrew Burns: They’re an opportunity to make an architectural statement, with a few agendas. Gene Sherman’s agenda with Fugitive Structures is to allow a wider public audience to experience something made a high level of architectural intent. Gene talks about how often with this type of installation at international biennales there are so many works that people pop their head into for a few minutes, then head out somewhere else. SCAF wanted to create something here where people might linger. It’s not strictly speaking “functional” but it’s not static either. It has three modes: performance mode (as a stage set), architectural statement and art installation. All three have different degrees of practical thought and conceptual territory behind them. The building responds to the courtyard, almost presenting frontally to that so it sets it up like a stage or performance space, much like Australia House did in Japan. The hope is for it to be animated with various events and activities. And I’ve been asked to participate in other layers of bringing works such as film into the space. It’s really exciting for me to have the chance to operate in that ambiguous territory. *(Gene Sherman is chairman and executive director of SCAF.)

PS: It’s interesting that Fugitive Structures is initiated from the art world. As an architect, do you approach your projects with artistic intention?

AB: A lot of contemporary art collapses that distinction between the two, and uses the techniques of architectural project management, and that’s where this initiative sits. Gene is very interested in architecture. There’s definitely a different way of thinking, a wider sort of logic in contemporary art, than there is in architecture I would say. I tend to approach my work seeking a purity of intent, and that probably sits closer to contemporary art.

Burns’s impression of the Crescent House pavilion in situ.

PS: Tell us about the building.

AB: One of the basic issues of the project was that it needed to be twenty square metres maximum (to avoid development consent), and a maximum of three metres high. I guess the basic concept is that it takes a fairly ordinary element – in this case a rose-apple hedge – and expands upon it. It’s quite a beautiful thing in itself, but with the building framing it, it’s transformed into a broader landscape – or at least the suggestion of one. I think that has a sort of social or sustainable idea behind it too, which is that we can create spaces within a dense city that have the sense of nature’s vastness. Planting can become part of a building’s external fabric – and I don’t mean that in the clichéd “vertical green wall” kind of way.

PS: How did the hedge influence your design?

Landscape as structure: a render of the view looking through to rose apple hedge.

AB: The building explores another ambiguous territory – the space between architecture and landscape, and the idea of landscape as more than just the setting for a building, or a green wall. It sounds over the top, but a hedge is architectonic. It’s structure, and more than just a backdrop, it’s a kind of catalyst. Initially the building was going to sit flush against the hedge so the space didn’t have a back to it, and the thick nib would be lost inside the greenery. But I’ve pulled the pavilion slightly away from the hedge now for a few reasons.

PS: Depth of field?

AB: Yes. And to reveal more of the hedge and the space around it, and to let more sun onto it – it’s a living plant after all. Also, when I was there recently, the breeze came through and the leaves would suddenly start moving, which animated the whole thing in a way I hadn’t considered. So, pulling the building back allows those fleeting movements to register.

Crescent House render of front (without screen).

PS: Tell us about the materiality of the building, particularly the blackened wood.

AB: Yaki Sugi – “charred cedar.” It’s a traditional Japanese technique used to extend the life of timber and preserve it against insects and rot. The architect Terunobu Fujimori uses it. It’s where you have a fire pit or a steel drum and you tie three planks together in a triangle then put that over the fire so the flame goes up through the middle, then you turn it over so it’s evenly burnt. It’s then put out onto the ground, and sprayed with a fire extinguisher.

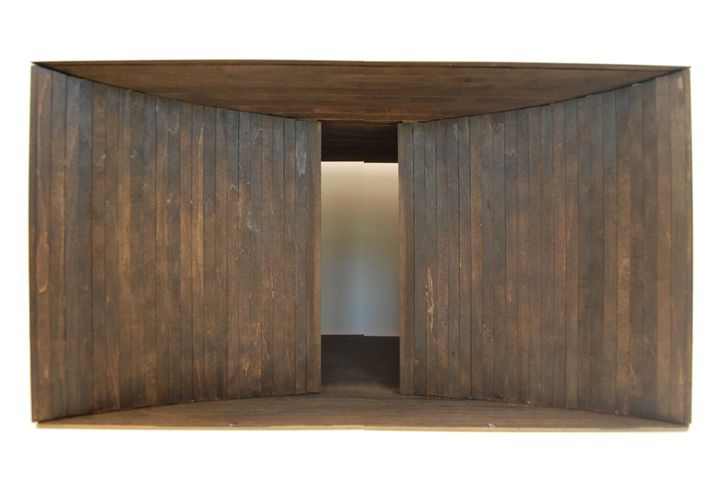

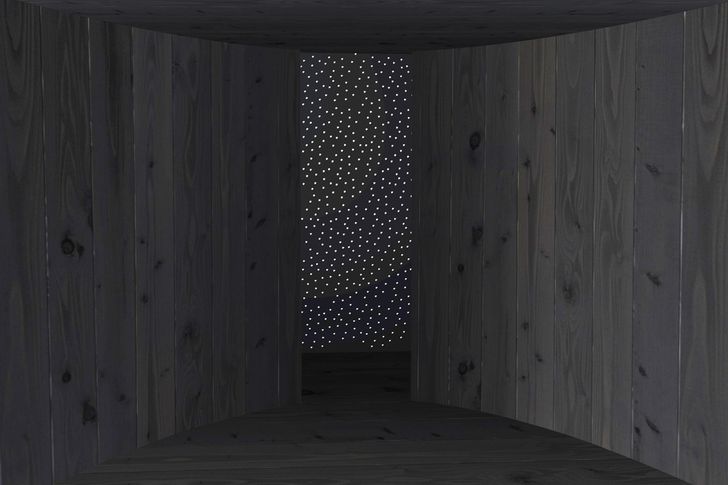

The timber-lined interior of Crescent House looking out through the steel screen.

There are different ways of finishing it. You can scrape some of the charring off to be smooth, or leave it with that textured, almost reptilian, effect. Then you oil it. We’re going to have the textured effect on the outside surfaces, and smooth on the inside. So you’ll have these really crisp arcs cutting out of a rough block of burnt wood.

It’s actually got cultural relevance here too. Early Australian farmers would burn the bottom of their timber fence posts before planting them into the ground, for the same reason – preventing rot. There’s a European tradition of this as well. Different timbers react differently. We’re looking at using Tasmanian oak because with Australian hardwoods, while you can blacken them, they don’t give you that rich texture, which is why we’re looking at a softwood. There are a couple of companies in Australia who roast timber (at about 250 degrees) which changes the properties, and we’ll do some work with them to sample the oak. So there’s an R&D component to Crescent House which I’m really excited about. The other element is the steel screen, crudely punctured, which will be left to rust naturally.

PS: It’s not really a house at all, so where does the name Crescent House come from?

AB: I’ve called it that because it’s the intersection of two arcs. An arc is very suggestive geometry. It suggests the path of the sun, the shape of the moon, those kind of things. By having one timber plane intersect another you create these two very sharp points that are the entries to the space. This creates a quality to those edges that’s both extremely fragile and very robust. And pointing away in both directions, they offer that beautiful experience of looking out – a sense of infinity. Then, when you turn around, you’ll see through that screen at the front – which is just a piece of black perforated steel, and that gives a sense of the night sky, of looking inwards.

The raked Zen Courtyard at SCAF in Sydney’s Paddington where Crescent House will be installed.

Image: Courtesy of SCAF

Fugitive Structures

Fugitive Structures is an invitation-only competition for emerging and mid-career architects to design a small-scale temporary pavilion for the SCAF Zen Garden in Paddington. The project has a four-year plan – to exhibit from 2013 to 2016.

Converting her commercial art gallery into a foundation allows SCAF director Gene Sherman to pursue her agenda of creating broader curatorial content that crosses into architecture and brings in names from her “persons of interest” list and her visits to London’s Serpentine Gallery became the catalyst for Sherman to set up Fugitive Structures.

“I’ve been to the Serpentine Gallery thirteen times,” says Sherman. “The Summer Pavilion series has been a success beyond measure. People flock to this nineteenth-century tea house in Kensington Gardens. It’s very small for a public gallery. And I thought, we’ve got a garden – a raked Zen Garden in Paddington. It’s small, it’s urban, but still, you can build a structure in it.” Together with BVN, the project’s architectural partner, Sherman helped compile a shortlist of ten small Australian practices to invite to submit. In the coming years they will open the field to entrants from the broader Asia-Pacific region.

Andrew Burns was not personally known to Sherman, though Australia House and the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale it hosts were very much on her radar, and his proposal aligned with her ambition for the space. “Andrew’s design was the quietest, modest, and in a way, the most obvious choice for the pavilion. It incorporates the landscape and frames the hedge so beautifully. It’s a remarkable hedge – it’s grown from waist-high to the size of a building since we took this site in 1991. Apart from the simplicity of his design, Andrew is so articulate about his ideas, and with a project like this, where you’re trying to reach into the community, it’s important that the architect can speak well.”

Exhibition

Open 22 March – 14 September 2013 Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation

Andrew Burns, Gene Sherman and BVN will talk about Fugitive Structures for Woollahra Festival on 17 November.