The recent announcement by the Victorian government that work on restoring Flinders Street Station will begin, sans design team, seems to lay to rest any hopes, however faint, that the 2013 international ideas competition for the station would lead to a visionary, architect-led built outcome. Sadly, but perhaps not surprisingly, this is not the first time a high profile international design competition in Victoria has failed to yield concrete results (so to speak).

The Victorian government’s 1978 Landmark Ideas Competition offered $100,000 in prize money (worth close to $500,000 in today’s terms) for proposals for a Melbourne “landmark” on the site of the Jolimont rail yards (where Federation Square currently sits). It generated 2,300 entries from 24 countries, none of which resulted in the hoped for landmark but all of which can still be found safely stored in the archives of the Public Records Office Victoria. ArchitectureAU gained access to 91 of these for a look at the Melbourne “landmark” that could have been.

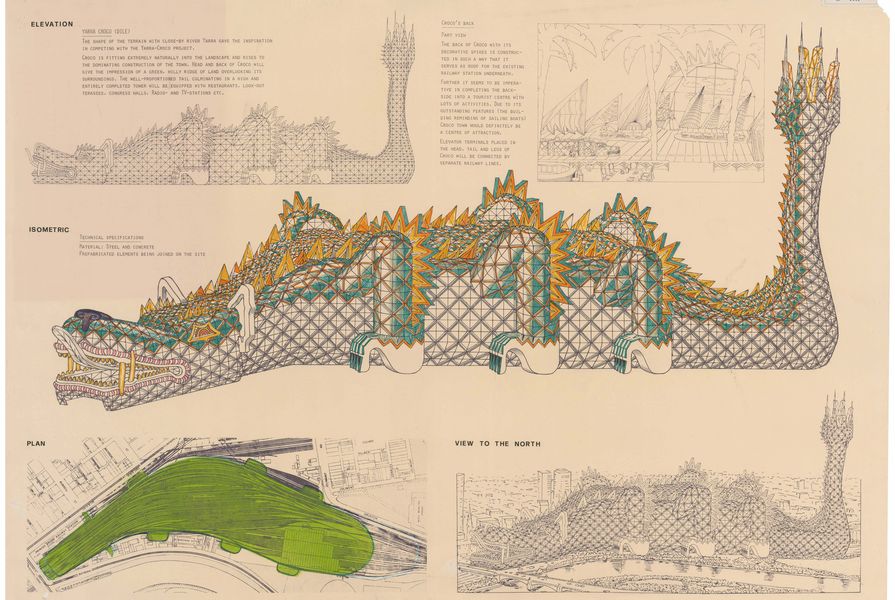

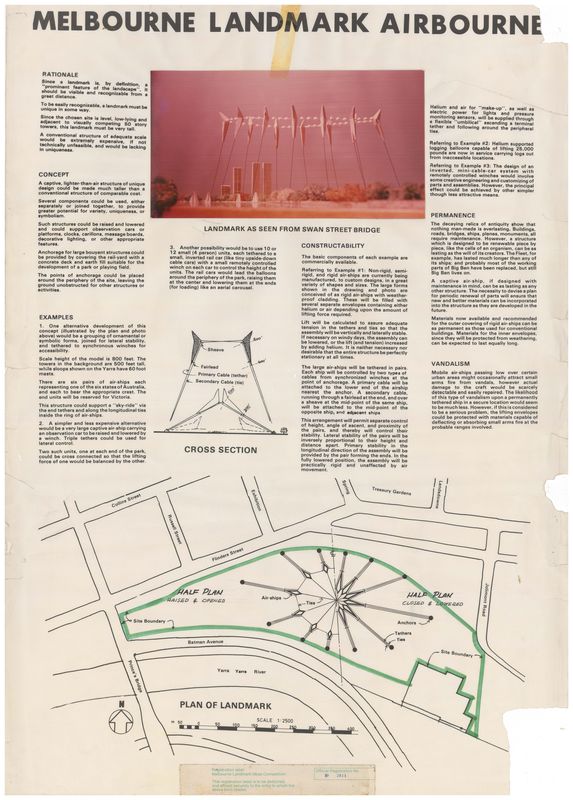

A pervasive theme among the entries was Australia’s propensity for “big” things, from Goulburn’s Big Merino to Nambour’s Big Pineapple by way of example. In the Landmark competition, the world offered Melbourne seven big kangaroos, five big (other) animals, three big letter ‘M’s, two big cricket wickets, a giant bird cage, a giant “fish garden,” giant chair, giant egg, giant brain, a closed hand with two fingers extended (a giant peace sign, if we’re being charitable) and a pair of “Monumental Mammaries.”

Entry in the 1978 Melbourne Landmark Ideas Competition: “Melbourne’s Monumental Mammaries.”

Image: Courtesy Public Records Office Victoria

Entry in the 1978 Melbourne Landmark Ideas Competition: Denton Corker Marshall’s The Great Wall of Melbourne/The Hanging Gardens of Melbourne.

Image: Courtesy Public Records Office Victoria

Among the less figural designs was a proposal by Denton Corker Marshall entitled “The Great Wall of Melbourne/The Hanging Gardens of Melbourne” – a two-kilometre-long giant, meandering glass house that would be up to 110 metres tall in parts. Denton Corker Marshall suggested the design would be “an extension of the City Square canopy on a vast scale” (the practice had recently won a 1976 competition for the design of City Square, which was opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1980 and later redeveloped in the 1990s). Denton Corker Marshall’s Melbourne Landmark proposal would include restaurants, bars and cafes linked by travelators inside the “vast” space. The architects suggested it would be “a place to spend hours or even days.”

Choosing a winner from the 2,300 entries proved to be an impossible task, and caused tensions among the assessment committee. As The Age reported on 14 December 1979, “[S]ome Landmark committee members [were] threatened with expulsion for allegedly making indiscreet remarks.” The lack of practicality of many of the designs led to the judges storming off the selection panel. In the end, 48 submissions were awarded, each taking a share of the $100,000 prize.

The shortlisted submissions included the aforementioned giant bird cage and two glass pyramid structures that predate the now world famous Louvre Pyramid in Paris by IM Pei (commissioned in 1984). Denton Corker Marshall’s proposal was not among the shortlist.

Shortlisted entry in the 1978 Melbourne Landmark Ideas Competition: “Melbourne World Exposition Centre.”

Image: Courtesy Public Records Office Victoria

The Landmark Committee proposed to the government that they proceed with development of the site by cherry-picking ideas from among awarded submissions to be “implemented over a period of eight years.” The Committee’s proposal included an ambitious wish list: a garden connecting the city to the river bank, a very tall tower with lasers and “the fastest vertical transport in the world,” a living exhibition of Australian fauna and flora, pleasure gardens, entertainment, sports and exhibitions, a convention centre, a casino, a model of inner urban residential development and a modern transport terminal. “The national tendency towards gambling could fund the development of these ideas,” the committee said.

Of course, not all of the ideas generated in the competition were impractical, but perhaps ahead of their time. Suggestions for bars, restaurants, cafes, gardens, a gallery, a tourist centre and even a TV and radio station have all become reality on the very site of the Landmark competition with Federation Square, completed in 2002 by LAB Architecture Studio and Bates Smart.

Shortlisted entry in the 1978 Melbourne Landmark Ideas Competition: “Mobility Park with Glass Stalk Landmark.”

Image: Courtesy Public Records Office Victoria

The competition was the subject of a 2012 exhibition, Missing the Mark, curated by Kate Luciano. As the exhibition catalogue read, “The Melbourne Landmark Ideas Competition sought an Eiffel Tower or a Statue of Liberty – a landmark that would […] as the competition brief explained, ‘put Melbourne on that elusive world map’.”

Missing the Mark speculated that envy might have motivated the competition’s organizers, coming as it did just five years after the completion of the Sydney Opera House: “It was amid a mood of civic despair, and a pervasive feeling that Melbourne was falling behind its rival to the north, that the Landmark Competition was launched.”

It might have put Melbourne on the “elusive world map,” but it drew a lacklustre reception from the local public. As The Age wrote on 16 July, 1979: “It had been lauded in New York and pooh-poohed in Prahran.” At an exhibition of the 48 shortlisted entries, “only a modest crowd came to look,” the newspaper reported a few months later.

An editorial in the Melbourne Herald newspaper described the competition as a “marvellous mish-mash.”

“Even though lured by $100,000, [the genius ideas] have proved elusive in our landmark competition for the Jolimont railyards as they have in virtually all other similar searches for the sudden divine spark in many countries in the world – Sydney Opera House always excepted.”

The government abandoned the project entirely by 1979. The Age newspaper and ANZ Bank ran a subsequent competition that turned even more farcical. Of the 450 entries, “about a dozen had any claim to sanity,” said one of the judges Phillip Adams, who was also on the Landmark competition assessment panel. (The Age, 16 July 1979.)

Ten $50 consolation prizes were awarded in The Age/ANZ Bank competition, including one to John Wardle of East Brunswick.