In the final days of 2017 the Queensland government gave the green light to the $3 billion Queen’s Wharf Brisbane casino, a colossal project that will occupy 12 hectares of government-owned land and potentially reclaim 15.3 hectares of the Brisbane River.

Coming just days before Christmas, and with the result at that point perhaps expected, the decision received a somewhat muted response. A response overshadowed by the outcry over another case of public space being given over to a private entity — the announcement that Apple would be planting a flagship store in the middle of Melbourne’s Federation Square.

Since the casino developer Destination Brisbane Consortium was named as preferred proponent for the site in July 2015, however, the proposal has been pilloried from all corners. The Australian Institute of Architects, the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects and the Urban Design Alliance all questioned the appropriateness of building a casino so close to the seat of government, while former Queensland government architect Michael Keniger told ArchitectureAU in 2015, “It’s unfortunate that such a large scale development driven by the needs of the gaming floor of the casino overrides what was a coherent government precinct and overrides its setting.”

The proposed Queens Wharf Brisbane casino resort masterplanned by Jerde Partnership will sit on around 12 hectares of riverfront land.

Image: Destination Brisbane Consortium

In the lead up to Economic Development Queensland’s decision, another criticism of the proposal arose. Outspoken Greens councillor Johnathon Sri in the City of Brisbane – referencing an obscure passage of the development application’s Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design Report – claimed that the Queen’s Wharf development was an example of “hostile architecture” coming to Brisbane.

“Buried down on page eight of the report was a recommendation that the design of public space infrastructure includes elements to discourage anti-social behaviour – and they specifically mention armrests on public benches to discourage people from sleeping on them,” Sri told ArchitectureAU.

“That says quite clearly that the developer, and by extension the government that approved this project, have an active interest in discouraging poor or homeless people from using these public spaces.

“And that’s clearly quite problematic.”

Fabian Brunsing’s Pay and Sit Bench artwork.

Image: Fabian Brunsing

The concept of hostile architecture, or at least of architecture that aims to prohibit certain behaviours and exclude certain people, is not a new one. University of Melbourne researcher James Petty told ArchitectureAU that the design of public spaces has always had a coercive aspect.

“With the design of any kind of public space, it inherently has an intention around controlling people’s behaviours and movements,” says Petty, who recently completed a PhD in Criminology that looked at how homelessness is regulated and criminalized in Melbourne.

“Footpaths [for instance] are designed to make people walk there, instead of anywhere else.”

The design features described in Queens Wharf’s development application, however, are coercive in a different way, according to Petty.

“Anything that targets specific uses that are characterized by marginalized groups, like people who lie down on benches – yes, I would say that definitely constitutes hostile architecture.”

The rise of hostile architecture

The concept of “Hostile architecture” and the discourse around more pernicious examples of coercive design have gained traction in recent years.

In 2008, Berlin-based designer Fabian Brunsing memorably satirized the privatization and monetization of public spaces with his retractable spike bench artwork; a public bench usable only for a fee.

While later reports that the concept had been taken up by a city in eastern China were almost certainly apocryphal, similarly confronting design elements in public spaces have appeared since – from the strategically designed Camden Bench to the pink lights installed at a Nottinghamshire housing estate designed to prevent loitering by illuminating teenagers’ acne.

One of the more visible instances came in 2014 when property company Property Partners installed spikes in front of a London apartment building as a way of deterring rough sleepers. Photographs of the spikes went viral, a petition to remove the “anti-homeless” spikes attracted well in excess of 100,000 signatories and the spikes were eventually removed.

The pikes installed by Property Partners in front of a London apartment building, which sparked public debate about hostile architecture in the UK.

Image: Harriet Wells

James Petty explained that there was a confluence of factors that contributed to the frenzy of discussion about the spikes: there was the newly powerful reach of social media, the fact that the term “hostile architecture” was just entering the vernacular and there was the aesthetics of the spikes.

“The spikes look hostile,” he said. “Their hostility, or their aggressiveness, or their kind of violence, is plainly evident.

“There are some examples in Melbourne where things have been installed to prevent homeless people sleeping in specific areas, but they’re not spikes. They’re things that are much more pleasant to look at, like large sort-of pot plants and crates full of pot plants and flowers. Flowers are pleasant things, much more so than spikes, so no one gets outraged about pot plants, but they seem to get outraged by spikes.”

Hostile architecture in Australia

The headline splashed on the Fairfax Media article that first published Johnathon Sri’s criticisms of Queen’s Wharf stated that the councillor was concerned the project was “bringing hostile architecture to Brisbane.” Sri actually maintains that hostile architecture has long been a factor in Australia’s cities.

Aerial view over George Street of the proposed Queens Wharf Brisbane casino resort masterplanned by Jerde Partnership.

Image: Destination Brisbane Consortium

“Hostile architecture is definitely becoming more prevalent in Brisbane, it seems to just pop up suddenly without much comment or discussion; there’s never really been an active publicly debated decision that says ‘okay from now on we’re going to introduce infrastructure to deter homeless people,’” he said. “It just happens gradually, over time.”

There have been some examples of hostile architecture in Australia receiving widespread attention. In 2015, the WA Department of Culture and Arts caused controversy by installing a sprinkler system used to prevent homeless people bedding down in the inner city. In 2013, NSW’s RailCorp was forced to back down after suggesting the use of “Mosquitos” – devices that emit a high-frequency buzzing noise only people aged 13 to 24 can hear – to deter graffiti artists.

But Sri said these more visible cases are exceptions to what is generally a hidden process.

“It’s not just the most common one of placing the armrest in the middle of the bench, but also window ledges designed with slopes, or architectural flourishes that make it hard for people to sit on window ledges.”

Bolts installed on the front steps of a building in France, to discourage sitting and sleeping.

Image: Docteur Cosmos

Julian Worrall, a professor of architecture at the University of Adelaide, told ArchitectureAU that the language around these kinds of design features is highly politicized, with proponents using the term “defensive architecture” and opponents “hostile.”

“We need to think about it in kind of a spectrum, from various forms of soft encouragement towards a kind of hardening, or indeed hostility, at the other end of the spectrum,” he said.

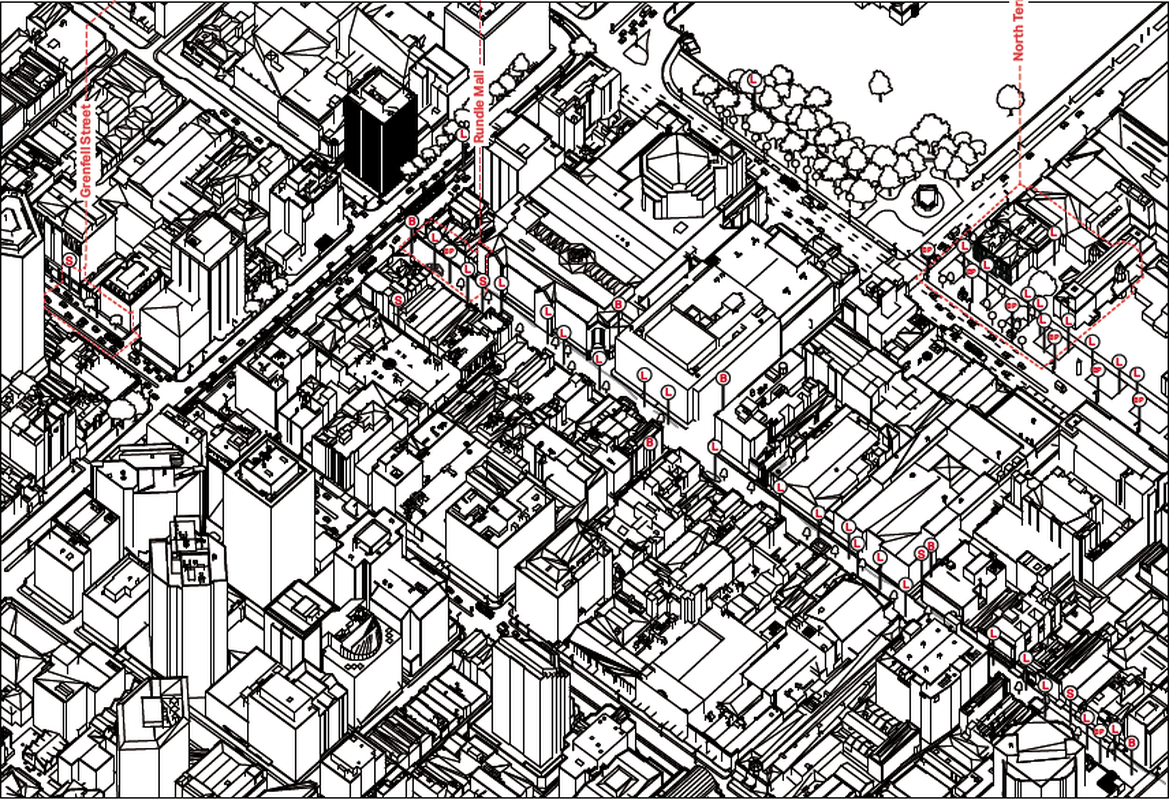

Working with a group of students, Professor Worrall produced a digitally augmented tour of defensive and hostile architecture in Adelaide for the 2017 Festival of Architecture and Design. Named “Hiding in Plain Site,” the tour aimed to “make visible the conflict within a city that is often hidden, mediated and managed through urban public space.”

A map of defensive and hostile architecture in Adelaide produced as part of the “Hiding in Plain Site” project.

Image: Proffessor Julian Worrall

“Australians live outdoors a lot of the time, particularly in a place like Brisbane, with its really pleasant weather,” he said. “So I think these minor defensive or hostile design interventions in public space – we need to be on guard against them in Australia [in order to] maintain the generosity of the public urban environment.”

POPS and privatization

While Sri agreed that it is necessary to encourage some behaviours and discourage others, he questioned how the decisions around these issues are made.

“The problem with the Queen’s Wharf development, indeed with a whole bunch of private development in Australian cities, is that design decisions are not being made democratically,” he said. “They’re being made by big developers or big corporations who fundamentally want to encourage uses of public space that align with their profit motive.”

It’s a line of criticism that draws on a field of academic enquiry looking at the influence of Privately Owned Public Space (POPS).

“It’s a phenomenon which is associated with the broader privatization of the provision of the infrastructures and buildings that constitute our cities,” said Professor Worrall. “And that slow privatisation, or creeping privatisation, has happened progressively since the late 1970s.”

“The problem is that a lot of what we might consider to be the public spaces of the city are actually being developed by and managed by private entities which are seeking revenue streams from a particular market, a particular substrata of the overall population.

“So there is an implicit conflict there.”

Professor Worrall believes that people will come to object to these kind of quasi-public spaces.

“I think as people become aware of the essential losses associated with [the privatization of public spaces] there may be an increasing demand to reinstate the public agencies that can deliver these kind of overall visions of inclusivity.”

What is to be done?

One of the problems associated with the proliferation of so-called hostile architecture, according to Sri, is its normalization and the tacit acceptance of those involved in shaping the public realm.

He believes that those involved in the design process of spaces like Queen’s Wharf need to do more. “I think architects, landscape architects, and other design professionals have an ethical responsibility to push back against this stuff and speak out about it,” he said.

“Architects can’t absolve themselves of ethical responsibility; they shouldn’t feel that they can just say ‘oh well, that’s what the project brief said,’ or, ‘I’m just doing my job.’”

“If your job requires you to actively make life more difficult for homeless people, then you should quit, it’s that simple.”

A Camden bench outside Freemasons’ Hall on Great Queen Street, London by The wub, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Professor Worrall sees a “genuine friction” in public spaces between different types of uses, and says there does need to be a negotiation between uses – for instance a group of skateboarders and a group of elderly ladies cannot necessarily use the same space at one time.

Worrall says that it is this friction, however, which is at the core of city life.

“If you sanitize that friction with these design interventions, to make it monoculture in some way, you lose some of that rub, that texture, socially, culturally, within that public space,” he says.

“That’s what I would think the designer should always be bringing into that conversation.

“And any enlightened developer ought to be receptive to that.”