There are many starting points when setting out to explore the current state of architectural education, as evidenced by a broad and expanding range of sources, references, opinions, concerns, manifestos, propositions, refutations and a sprinkling of objective assessments. The tumult of ideas, thoughts and critiques ranges over the value of education itself, the future of the profession of architecture and comparisons with other disciplines that, taken together, suggest a fervour of action and reaction, of future-focused innovation and enterprise. Not so. At the base of it all, at least here in Australia, there is a relatively settled set of expectations and educational practices in place, the residual outcome of years of battling to shore up the presence of the discipline of architecture within tertiary education – an arena beset by its own uncertainties concerning the future, its structure and the nature of national priorities as translated into the funding of the sector.

Amongst the clamour of comment and critique the unequivocal optimism extended by Mark Wigley rises above the general melee. When Dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, Wigley proclaimed, “Education is all about trust.” He went on to say, “A good school fosters a way of thinking that draws on everything that is known in order to jump energetically into the unknown, trusting the formulations of the next generation that by definition defy the logic of the present.”1 Such confidence in the future is heartening but the realities of moving towards that future threaten to overwhelm the premise that such resilience is both achievable and sustainable. Certainly, such optimism seems to evade the profession of architecture in the UK, where it has recently undergone several cycles of introspection and external review, including the Farrell Review of Architecture and the Built Environment,2 the RIBA’s extensive review of architectural education,3 and the various reviews and critiques offered in the professional and popular press, including, most notably, the wholesale probing of the profession and architectural education by Peter Buchanan in The Architectural Review ’s Big Rethink series.4

The need to examine the future of the profession and the state of architectural education in the UK was primarily driven by a perception that there was an increasing divergence between the nature of academic programs and the needs of architectural practice. Further, there was a necessity for academic institutions to conform to the Bologna Process concerning program length, nomenclature and requisite educational benchmarks. The UK government’s decision to triple the fees to study architecture from £3,000 to £9,000 per year from 2012 gave an additional cause for enquiry as the increase was thought to prejudice access to a profession that entailed such a lengthy course of study to enter a relatively poorly remunerated profession.5

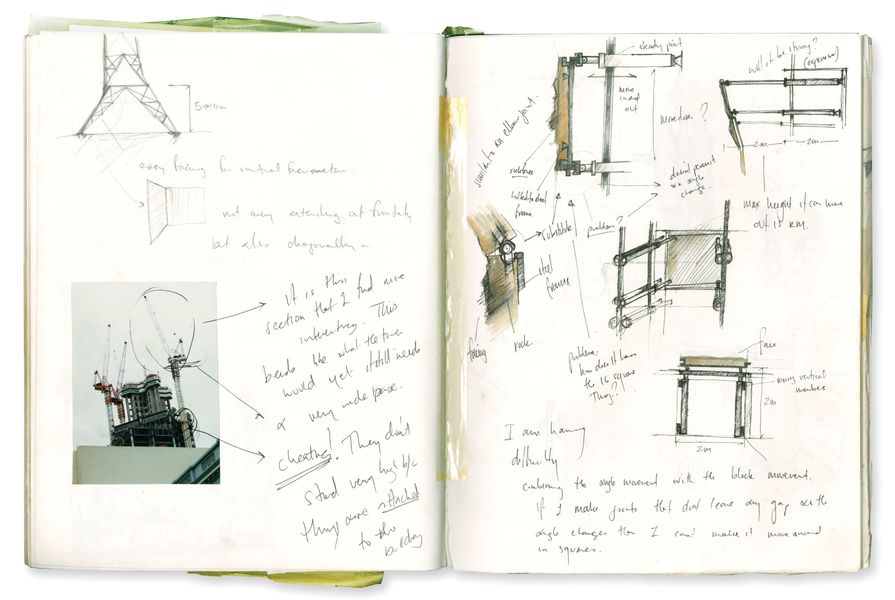

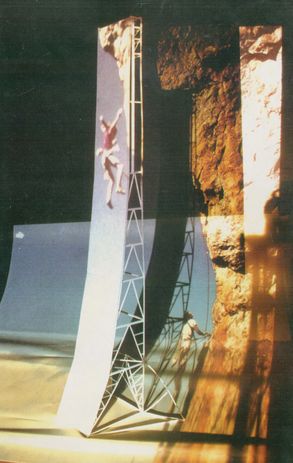

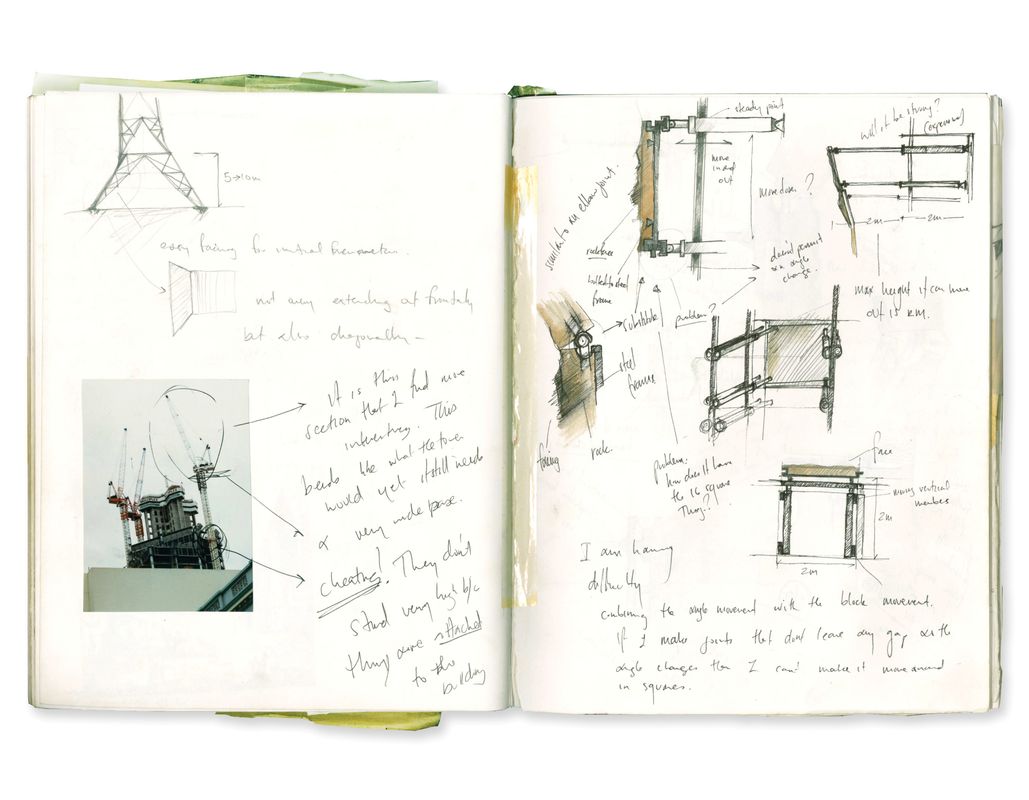

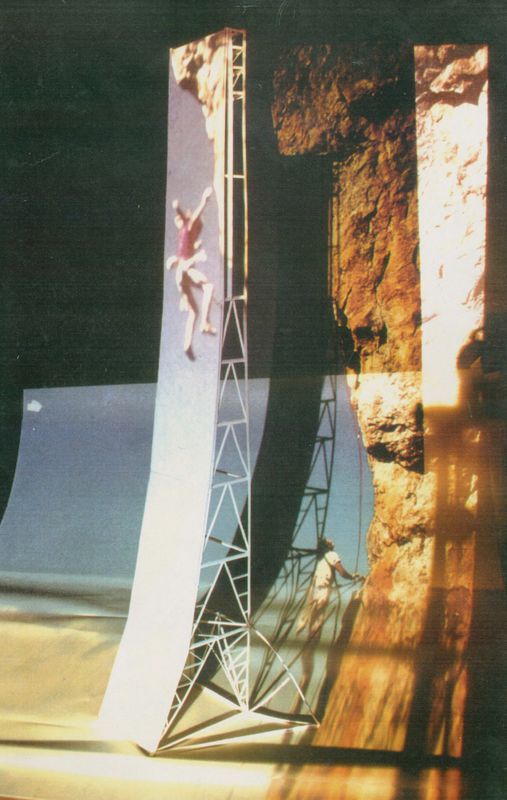

A drawing by Nikolas Koulouras in 1991, as part of a first-year architecture studio run by Bill Busfield at the University of Western Australia. The project was titled The Climber and the Wall. Image:

Nikolas Koulouras

The recommendations of the RIBA review include the introduction of a more flexible structure of education, providing a surety of registration as an architect on graduation. Professional practice experience is to be integrated within an overall seven-year program and professional practice subjects are to be introduced in the earlier years of the degree programs. The process o f implementing the recommendations is far from complete and the eventual effect of the recommended changes will depend on how the universities providing the academic programs respond. At this point it seems unlikely that these adjustments to current RIBA policies will lead to a fundamental change, either in architectural education or in the profession, and yet many see the need for urgent and thoroughgoing change.

The Radical Pedagogies research project at Princeton University led by Beatriz Colomina explored and documented a range of experiments in architectural education of the 60s and 70s. Colomina notes that “A shared understanding amongst these varied radical practices was that a new modus operandi for the discipline could only be created if traditions were questioned, destabilised, undermined or even destroyed.” The burning of the Architecture School at Yale was possibly the most dramatic signal of revolt, while irregular workshops such as those arranged by Giancarlo De Carlo with members of Team 10 and Alvin Boyarsky’s Summer Schools at the Architectural Association, along with a broad range of initiatives and experimental pedagogies energized by Cedric Price, John Hejduk, Joseph Rykwert, Dalibor Vesely and so many others, illustrate the many attempts to develop innovative approaches to architecture.

A contrast is made with the adventurous and often anti-institutional nature of these idealistic and sometimes disruptive ventures with the observation that today “Architectural pedagogy has become stale. Schools spin old wheels as if something is happening but so little is going on … Curricular structures have hardly changed in recent decades. As schools appear to increasingly favour professionalization, they seem to drown in self-imposed bureaucratic oversight, suffocating any possibility for the emergence of experimental practices and failures … it is all so timid in the end. There is no real innovation.”6

A further challenge to the loss of adventure in architectural education is given by Daisy Froud and Harriet Harriss, editors of Radical Pedagogies: Architectural Education and the British Tradition. In the introduction, Harriss states, “The decision to make the book was the result of extreme fatigue. I’m not tired of my job but rather of the endless questioning of how we make architectural education ‘better.’ Better is no longer good enough.”7 The sense of ennui is deceptive. A selection of lively histories and pungent enquiries are accompanied by critical and provocative case studies of current attempts to enliven educational programs in architecture in the UK. Efforts to enrich or overturn conventional educational practices are explored, achievements mapped and frustrations vented. The contributions have a rawness born of experience and an authority derived from the effort taken to construct other futures. It is hard to ignore the gritty issues faced by Ruth Morrow when leading an architecture school in the post-conflict city of Belfast8 or the pithy saga offered by Jack Self in “Factories or Malls?” where he recounts his experience as a student enmeshed in the commodification of education.9 Fledgling attempts at generating alternative educational structures and strategies are charted, many of which are linked by a move towards shorter courses and greater involvement with community-based needs, problems and opportunities.

Possibly the most ambitious and best publicized of these ventures is the London School of Architecture (LSA),10 which accepted its first enrolments in 2015. Headed by founder Will Hunter and three other directors, the LSA is largely freestanding and independent of any institutional bureaucracy. It has a functional link with the London Metropolitan University through the Sir John Cass Faculty of Art, Architecture and Design, which provides the necessary academic validation for the two-year postgraduate course offered by the LSA – equivalent to the graduate master’s programs offered by architecture schools in Australia. Recognition of this program by the UK’s Architects Registration Board has been sought, which Hunter trusts will lead to validation by the RIBA.

A drawing by Nikolas Koulouras in 1991, as part of a first-year architecture studio run by Bill Busfield at the University of Western Australia. The project was titled The Climber and the Wall.

Image: Nikolas Koulouras

The LSA has a minimal administrative structure and is essentially nomadic, occupying space when needed and as available across the city. The impetus for its formation was given by the positive and supportive response to an article by Hunter, when executive editor of The Architectural Review, that posed the question as to why there should not be a route for architecture students outside the university system.11 The LSA model works jointly with a network of forty or so supporting practices to offer a two-year program that includes immersion in practice during the first year of study, entailing three days per week in a paid position and two days of study. The salary earned of £12,000 effectively covers the LSA course fee of £6,000 per year. The second year is full-time within the school but thought of as the first year of practice, with students pursuing individual lines of enquiry guided by tutors drawn from the practice network. The seeming fragility of the LSA in its incipient state is offset by the standing and goodwill of its many advisers, supporters and contributors, including Nigel Coates and Leon van Schaik, who provide academic oversight. The initial cohort of students is thirty per year, and the size of the school will be limited to sixty or seventy students as the venture is not driven by a need for growth or financial return. The declared ambition is to offer an alternative choice alongside the conventional options for education for the profession of architecture. It is a choice based on an integration of study with ideas-led practice, driven by the confidence and trust of the students themselves and given context and character by its intertwining with the issues and options provided by the changing city in which the school is based.

In Australia there are no such adventures – as of yet. The stirring of debate and review concerning the nature of architectural education here is intrinsically linked to the standing and purpose of the profession in Australia. As in the UK, the profession guards its status as a regulated discipline where the title of “architect” is protected through codified registration procedures that prescribe the attributes of architectural education jointly with the Australian Institute of Architects’s policies. This protection has been challenged as an impediment to fair trade and each time has been upheld by the view that there is a risk to the public if buildings and related structures are not designed to meet appropriate standards. The protection offered by registration is relatively weak and is eroded further by the increasing marginalization of architects caused by changed project delivery systems and competition from a plethora of sub-disciplines. Of particular concern is the diminishing of clients’ regard for an architect’s contribution – partly due to a lack of understanding as to what a full architectural service can deliver.

The growing sense of malaise and uncertainty has a limiting effect on the nature and structure of architectural education. In Australia there are eighteen accredited, university-based, five-year programs in architecture that lead to registration. The most notable change of structure in recent years has been the introduction of a coursework master’s program by all institutions following the adoption across the education system of a two-degree structure with an initial undergraduate degree. This change provides alignment with the Bologna Process and with the structure and nomenclature largely employed across the Asia-Pacific. A critical argument made in favour of the change was that it would enable programs to become more diverse and so enrich the overall range of course offerings to sustain a breadth of needs in the discipline. The envisaged differences of pedagogy or purpose have yet to strongly emerge, with the principal differences between programs derived from their historical character, their location, their access to cognate disciplines within their institution and their leadership.

Big West House was a collaborative project for Melbourne’s Big West Festival. The “house” was designed by NMBW Architecture Studio and fabricated by Victoria University TAFE carpentry students, while the “furniture” was produced as a design-make studio at Monash University School of Architecture, run by Torafu Architects and NMBW Architecture Studio.

Image: Peter Bennetts

One notable difference in structure is provided by the University of Melbourne, where the “Melbourne Model” (now the Melbourne Curriculum) requires most students to undertake generalist undergraduate programs as a prerequisite for entry to specialist and professional master’s degrees. This enables entry into a three-year master’s program in architecture for graduates from Bachelors of Arts, Biomedicine, Commerce, Music or Science completed with a design and history subject at Melbourne. This brings together students with a broad variety of skills and disciplinary knowledge, with those entering from an orthodox three-plus-two pathway for graduates of the Bachelor of Environments degree continuing to a two-year master’s program.

A further variation is offered by Bond University’s Abedian School of Architecture, where the conventional five-year academic program may be undertaken in an intensive form. Courses are offered on a trimester basis, which enables the course to be completed in three-and-a-third years of continuous study. Understandably, many students shape a program that allows them to weave in and out of the program for periods of time in professional experience or to travel. A private university, Bond is aiming to drive a quality agenda within its architecture program by restricting overall enrolment to a target of 150 EFTSU and by providing extended teaching contact time so as to best harness its purpose-built home specifically designed to support studio-based teaching and learning.

Overall, architectural education in Australia has a signal advantage over that provided in many other parts of the world. Here, students can expect to be involved in the design of buildings that they will see built and from an early point of their careers they will be involved in the creation of built environments, which gives their education a tangible purpose and outcome. There are also advantages derived from coherence across the nationwide system that enables movement between institutions and all programs have at their core an active and well-defined focus on architectural design. Common difficulties are primarily those caused by pressure on the funding of programs in Australia and particularly in those institutions where architecture is not seen as central to the host university’s strategic agenda. The battle for funds, for space and for sufficient staff numbers is directly related to the recognition of performance and acknowledgement of the relevance of the needs of the discipline. With supplementary funding and academic career progression increasingly tied to research achievement, architecture has struggled to gain sufficient recognition for its particular core purposes, paradigms and achievements. Inevitably, the energy and time of the academic staff are increasingly directed to research activity, with teaching contact more and more dependent on the contribution of tutors drawn from practice on a sessional basis. The contribution made by external tutors across all institutions is extraordinary and this direct input from the profession warrants better recognition. Architectural education as it is currently structured could not flourish without it. That said, a significant risk of being so dependent on external teaching staff on sessional appointments is that the long-term direction of a course will weaken without clear overarching purpose, coordination and leadership sustained and delivered over time. Even the best practitioners are not necessarily good pedagogues. They are unlikely to be across the latest teaching techniques, resources and policies or fully aware of how their efforts mesh with the teaching in other parts of the program. They also have little purchase from the lower levels of the stratified hierarchy of a university to influence policy or strategic direction.

Held as part of the 2016 Asia Pacific Architecture Forum, the Sulcus Loci installation by University of Queensland (UQ) master’s students of architecture, multimedia design and interaction design houses an experiential artwork by artist Svenja Kratz and composer Eve Klein of UQ’s School of Music.

Image: Dianna Snape

There is also the further risk of the emergence of complacency and a weakening of standards if convenience is allowed to overcome incisive and purposeful teaching and if contact hours are curtailed, group sizes increased and student expectations allowed to drop. Too often, artfully constructed “hero images” dominate a student’s presentation offered for open critique, with the design idea and rationale suppressed or absent. In recent correspondence, Tom Heneghan, the most forgiving of critics, stated that “My problem is that recent student work often seems (to me) pointless. The computer can churn out any number of plans and sections but they rarely seem to illustrate an idea worth talking about. Because a computer can create twenty different sections of a scheme, the student prints them all rather than the two sections that actually tell the story.”12 This is a comment as much concerning the teaching and the expectations of the program as it is tacit expectation of the student that there is more weight to be placed on an image than on a “worthwhile or challenging or enlightening or novel or simply interesting idea” (Heneghan again).

Such concerns raise the significant issue of the nature and role of the design studio that traditionally has anchored architectural pedagogy. Fittingly, this and related issues and possibilities are the subject of the inaugural publication in a series supported by the Association of Architecture Schools of Australasia (AASA), Studio Futures: Changing Trajectories in Architectural Education, edited by Donald Bates, Vivian Mitsogianni and Diego Ramírez-Lovering and reviewed elsewhere in this issue of Architecture Australia by Harriet Harriss.

Given the diversity of issues that will determine the future of both the profession and architectural education it seems appropriate to quote the closing words of Don Bates’s essay “Past Futures and Future Pasts: The Architecture Studio,” to be found in Studio Futures: “To end (if not conclude), is to suggest that within the context of a discipline that appears in danger of losing its disciplinary edge – caught between a nostalgia for the lost comfort of professional certainties, a diminishing list of roles and responsibilities and a future that is too impatient to wait for a calm re-evaluation of the practice of architecture – the studio is either at its end as a primary mechanism in the formation of an architectural cognition or the studio offers a unique pedagogic tool and system producing a mode of education and knowledge formation that is better suited and better equipped for a transforming professional world.”13

For my part, my separation from day-to-day involvement with architectural education over the years since my time as the Head of Architecture at the University of Queensland and my subsequent exposure to the pedagogies employed by other disciplines across the breadth of that university reinforce for me the issue of trust raised by Mark Wigley. Unquestionably, I trust that architectural education will evolve to match the changing nature of the profession and to adapt in a positive way to the changing pressures, challenges and new opportunities within higher education. When invited to address the very first conference sponsored by the AASA in 2000, I said, “If the future of architectural education is to be assured then it is essential that we are fully informed about the pressures to be met and confident about the strengths of our discipline. We cannot afford to be passive, complacent or compliant. There is little value in using our energy and intellectual capital to merely protect what we have been left with. We have to be assertive, to be strongly r epresented in the key decision making bodies and to exert influence in the community, in the profession and in academia.”14 Despite all that has occurred since, this remains my view.

1. Mark Wigley in Michael Chadwick (ed), “Back to School: Architectural Education – the Information and the Argument,” Architectural Design, vol 74 no 5, Sept/Oct 2004, 13.

2. See farrellreview.co.uk.

3. See architecture.com/RIBA/Aboutus/Whoweare/RIBACouncil/RIBAtoholdeducation

reformmeeting.aspx.

4. Peter Buchanan, “The Big Rethink Part 9: Rethinking Architectural Education,” The Architectural Review, 28 September 2012, architectural-review.com/today/the-big-rethink-part-9-rethinking-architectural-education/8636035.fullarticle.

5. Oliver Wainwright, “Towering Folly: why architectural education in Britain is in need of repair,” The Guardian, 30 May 2013, theguardian.com/artanddesign/architecture-design-blog/2013/may/30/architectural-education-professional-courses.

6. Beatriz Colomina, Esther Choi, Ignacio Gonzalez Galan and Anna-Maria Meister, “Radical Pedagogies in Architectural Education,” The Architectural Review, 28 September 2012, architectural-review.com/today/radical-pedagogies-in-architectural-education/8636066.fullarticle.

7. Daisy Froud and Harriet Harriss, Radical Pedagogies: Architectural Education and the British Tradition (Newcastle upon Tyne: RIBA Publishing, 2015), xii.

8. Daisy Froud and Harriet Harriss, Radical Pedagogies, 115.

9. Daisy Froud and Harriet Harriss, Radical Pedagogies, 59.

10. See the-lsa.org.

11. Will Hunter, “Alternative Routes for Architecture,” The Architectural Review, October 2012.

12. Tom Heneghan in correspondence with Michael Keniger, December 2015.

13. Donald Bates, “Past Futures and Future Pasts: The Architecture Studio,” in Donald Bates, Vivian Mitsogianni and Diego Ramírez-Lovering (eds), Studio Futures: Changing Trajectories in Architectural Education (Melbourne: Uro Publications, 2015), 75.

14. Michael Keniger, “From Defence to Attack: Critical Contexts and Necessary Futures for Architectural Education,” in Gary Moore and Louise Trevillion (eds), Architecture + Education 2000 (Sydney: University of Sydney, 2000), 13.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 21 Oct 2016

Words:

Michael Keniger

Images:

Dianna Snape,

Nikolas Koulouras,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2016