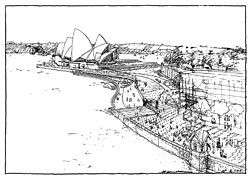

Redevelopment of Lower Concourse Level, Sydney Opera House, by Alex Popov, the inaugural winner of the AA Prize for Unbuilt Work, described by juror Shane Murray as “a true design investigation in that there is an observation of an existing state of affairs, a hypothesis and a speculation”. Architecture Australia, January/February, 1993.

Cover of Architecture Australia, January/ February, 1994, announcing that year’s winners of the AA Prize for Unbuilt Work.

Opening spread from Architecture Australia, January/February, 1994. The year’s winner, Port Adelaide Housing, by Michael Markham and Abbie Galvin, described by juror Ian McDougall as “alternative concepts for living to those sponsored by the ignorant real estate industry”.

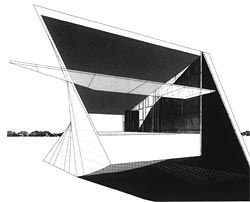

Opening spread from Architecture Australia, March/April, 1995. The winner was The Embrace, by Also Architecture Studio, Alice Hampson and Sheona Thomson. “A family house of sensual experiences.”

Opening spread from Architecture Australia, March/April, 1997, with the year’s winner, Knot Building, by RMIT student Nicholas Koulouras. “An audacious, exploratory, well-researched and unusually creative attempt to literally tie up architecture’s unravelled strands of theory at the end of the millennium”.

Opening spread from Architecture Australia, March/April, 1998, showing the winning project, Incision, by Martine Merrylees of Deakin University. “It does enlighten your imagination. I haven’t got a clear picture and I prefer to leave it that way.”

Commendation for Urban Design, 1994, Camberwell Housing, by William Orr, Ronson Lui and Siew Ling Wong. “A useful model for the necessity of denser urban infill.”

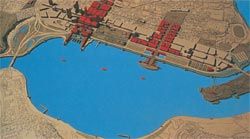

Commendation for Urban Design, 1994, Perth Foreshore, by Donaldson + Warn / John Sunderland. “A singular attempt to engage the city with the water”.

Commendation for Building Design, 1994, “Pool Pavilion” by Edmond and Corrigan. “Architecture meets the carnival.” All from Architecture Australia, January/February 1994.

Winner of the Architectural Concepts category, 1996, Kookynie Pied-A-Terre, by Richard Black. “A romantic notion ruthlessly abstracted.” Architecture Australia March/April, 1996.

Commendation 1997, Ode to the Lingering Garden, by Zahava Elenberg and Kelly Ratigan.

Commendation 1997, Minimata Memorial, by Anton James. All from Architecture Australia, March/April, 1997.

Architecture has an important tradition of “paper architecture” – projects that are unbuilt, and sometimes unbuildable, but which nevertheless make significant contributions to the development of the discipline. Think of the many projections of ideal cities over the centuries – works by Piero della Francesca, Filarete and others of the Renaissance, Le Corbusier’s Radiant City, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City, Ludwig Hilbershiemer’s Vertical City, Constant Nieuwenhuys’s New Babylon, the Smithsons’ Golden Lane scheme, Léon Krier’s postmodern cities and so on. Think of the Neoclassical proposals of Étienne-Louis Boullée, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and Jean-Jacques Lequeu; the etchings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi; the futurist speculations of Antonio Sant’Elia; El Lizzitsky’s Prouns? and the work of the Constructivists; the imagined worlds of Superstudio or Archigram; the utopian visions of Buckminster Fuller; and the dystopian ones of Lebbeus Woods. The list could go on and on. Consider the drawings of Zaha Hadid and Daniel Libeskind, which had such an effect on recent architectural culture long before either architect started building. And then there are all the explorations, formal and otherwise, of the potential of digital technologies over the last decade or two.

Drawn works (whether made using pencil and pen or mouse and keyboard) offer an opportunity for speculation, polemic and theoretical exploration.

There is an idea that such work thrives in times of economic downturn, but economic prosperity also leads to a large number of unbuilt projects languishing in the architects’ plan drawers or on the server – endless competition entries, works that did not go ahead for myriad reasons, financial, political and otherwise. This is a different kind of work to the polemical projects listed above, but the ideas explored in proposals for apparently concrete projects might also make important contributions.

(Remember the impact of Diller + Scofidio’s Slow House in the early nineties, a project that was not built beyond its foundations, but which was highly influential due to its wide circulation through a variety of publications, including Progressive Architecture as the winner of the 1991 Progressive Architecture Design Award.)

But to have this kind of effect, unbuilt work needs to be known in the architectural community and beyond. It needs to go into circulation, to be considered, discussed and debated. To this end, Architecture Australia is reviving the AA Prize for Unbuilt Work, which ran through the 1990s.

As Ian McDougall, inaugural prize convenor, explained, this award was intended to enable work be seen while it was still contemporary. As he wrote, “Architectural ideas often have a currency as evidence of a convergence of cultural and aesthetic sensibility.” He was interested in generating conversation around such ideas at the time of their production, not years later and on the condition that they turned into a building. He argued that thoughtful, unrealized architecture should not be “looked down on as the stillborn product of an enervating process”, and he reminded readers that Seidler’s proposals for McMahon’s Point and Sydney Cove, and Edmond and Corrigan’s proposals for Parliament House or the Australian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale are as interesting as the projects that were indeed realized in built form.

The inaugural AA Prize winner, Alex Popov’s scheme for the redevelopment of the Sydney Opera House Lower Concourse, met the ambitions of the awards programme neatly. Juror Jackie Cooper described it as demonstrating “the necessary qualities of architectural thought, research, resolution and presentation that the award seeks to celebrate and foster.” But things were not always so rosy. In 1996 no award was given, and the jury commented that, “Like past juries, it was looking for more than the kind of excellence likely to earn a building and architecture award; it sought theoretically and aesthetically exceptional propositions, not necessarily resolved.” The jury was, however, encouraged by the entries in a new category, Architectural Concepts, that year won by Richard Black. This emphasis on investigating ideas through the medium of architecture was consistent throughout the life of the award.

During Davina Jackson’s editorship, the awards coverage also playfully indicated the subjective nature of awards generally, with the declaration of “this year’s bias”. In 1994 it was “towards those entries which express sparks of innovation, imagination and design skill, with relevance to issues of current and potential social impact, but not necessarily well-resolved schemes”, while in 1995 it was “towards humanist proposals concerned with emotion as well as amenity”. That year, the jury also made a political statement by giving a jury citation to an unentered work – Jørn Utzon’s proposals for the Sydney Opera House interiors.

Looking back over the issues of Architecture Australia that present the winning and commended schemes is intriguing for other reasons also. The prize certainly recognized well-known practitioners – Alex Popov, Edmond and Corrigan, Donaldson + Warn, to name a few – but it also brought younger architects, graduates and students to national attention. Many of these “unknown” winners are now respected figures in Australian architecture and landscape, both as academics and practitioners – Adrian Iredale, Anton James, Zahava Elenberg, Tony Chenchow and Stephanie Little, Alice Hampson, Sheona Thomson, Anthony Moulis and others. Such early recognition was a vital aspect of the prize.

The coverage is also interesting for what it suggests about the media of architectural production. It reminds us that drawing and modelling are means of exploration as well as modes of communication. And that as these media shift over time, the possibility of what the architect can think and show also shifts. The role played by modes of representation in the development of architectural ideas is often elided in architectural publications, which almost inevitably focus on a finished product. Publishing inventive unbuilt projects allows some kind of reflection on this also.

So what now? The AA Prize for Unbuilt Work fizzled out due to an apparent lack of interest and the 1998 jury’s sense that none of the entries warranted the prize. Will it be any different a decade on? We hope so. The architectural environment has changed, and once again an enormous amount of work is being produced that is not realized. The earlier award is remembered fondly by our readers, as an important part of architectural culture. We hope, therefore, that the architectural community will enthusiastically support this new phase of the awards programme by once again entering compelling work to engage, intrigue and inspire.

A call for entries will be included in the next issue of Architecture Australia (March 2007), with the winners published in January 2008. In the interim, we will whet appetites by bringing to our readers a selection of earlier unbuilt Australian projects that we think are worthy of further discussion. Together, the prize and the retrospectives will occasion a new phase in the consideration of unbuilt architecture in Australia.

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Jan 2007

Words:

Justine Clark

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2007